Matt Dillahunty's Bad Arguments

I recently had a debate with one of the most influential atheists. Here's how it went

1 Introduction

I recently debated one of the most influential atheists on the internet—a fellow named Matt Dillahunty—about God’s existence. Dillahunty is a new atheist of the standard sort—quite certain that atheism is right, not inclined to think very hard about the arguments against atheism. I think the debate went extremely well, but many of Matt’s fans seemingly haven’t gotten the memo, so I thought I’d take this article to describe his myriad errors.

In my opening statement, I argued that God’s existence is quite likely. First of all, God existing has a high prior probability. Even before considering specific evidence, it’s likely that God exists because God is a mind of the very simplest sort—one totally without limits. This also makes the God hypothesis distinctly non-arbitrary. I also argued God best explains fine-tuning, the fact that the laws we have can give rise to complexity, consciousness, and anthropics.

Lastly, I endorsed a broadly Bayesian epistemology. I suggested that when evaluating some hypothesis about the world, one should begin by looking at its prior—how likely it is before considering the evidence for it. Next, one should consider the evidence. Evidence is just anything likelier given a hypothesis than given its falsity.

So now, let’s see Dillahunty’s many, many ridiculous claims.

2 Dillahunty confidently denies math

While I won’t include clips for most of the claims—as it would be a pain to go through and find—this one was funny enough to be worth finding a clip of. Dillahunty confidently and abrasively denied math!

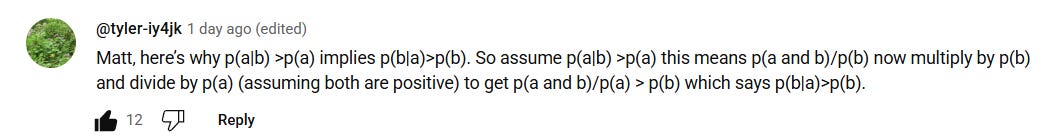

Specifically, he said that just because A is likelier given B than not B, that doesn’t mean B is likelier given A than not A. Problem: it does.1 This follows trivially from Bayes theorem and the definition of conditional probability. Whether some fact raises the likelihood of a hypothesis is a function of its probability given the hypothesis vs its likelihood given the falsity of the hypothesis. If the probability given the hypothesis is higher, then it’s evidence for the hypothesis. Many people pointed out Matt’s laughable errors in the comments:

In the above clip, when Matt denied math (and they say we theists deny math and science) I pointed out that this was an utterly trivial mathematical fact that you’d learn in high school stats and you could find out by asking chat GPT. A staggering number of comments are chewing me out for telling people to ask chat GPT.

Now, I know, I know, comments on a new atheist YouTube channel are slanted—more breaking news at 11. But I found this a particularly profound display of bias.

Matt made an easily Googlable false claim. I noted this and pointed out that anyone can check this very easily. Many, many more of the comments are complaining about me telling him he can find it’s false easily than people noting that it’s false.

Imagine, for a moment, if things had gone the opposite way. Imagine if I had claimed that there were only a finite number of prime numbers. Matt had replied by saying you can easily prove this wrong by asking Chat GPT and he was happy to walk me through the proof. I cut him off to say Chat GPT could be wrong and I wasn’t interested in the proof because it wasn’t evidence.

Would anyone—anyone—be on my side in such a case? Yet when the opposite happens, I’m seen as the one making ridiculous claims. The extent of the bias is beyond belief.

Almost all the comments are this one-sided. I think it’s pretty clear that I won the debate. Nathan Ormond, someone who is an atheist and no fan of me but actually knows something about philosophy, agrees with this assessment. One person emailed me saying:

Wow, that may have been the most lopsided debate I have ever seen, and I've watched quite a few of these kinds of debates. Watching Dillahunty struggle repeatedly with the most basic applications of Bayes theorem was almost surreal. When you suggested he ask ChatGPT and he went ballistic, I half expected the debate to turn into an impromptu mathematics lesson where you showed him a randomly selected person who was administered a certain test which came up positive for cancer and had him figure out what the chance was that it was a true positive was by estimating priors over and over again until you finally drilled the concept of a prior and its relationship with the strength of evidence into his head.

Thank you so much for doing that debate. I've read your blog for a while but have had some nagging doubts about some of the arguments you presented in your posts. Even though I couldn't point out specific flaws, I wondered if some arguments were just complex enough that I didn’t have the intellectual capacity to understand them deeply enough that I could spot real holes.

Watching Dillahunty make objectively false mathematical statements and repeatedly misunderstand the relationship between evidence and belief was one of the most encouraging things for my belief in God that I’ve witnessed for a while.

There were many times—as we’ll see—when Matt made a point, I responded to it, and then Matt ran to a different point without acknowledging concession on the first point. The opposite never happened. And yet despite this, there seems to be near-unanimity among the commenters that I lost. This isn’t that surprising—the commenters on Matt’s channel are extremely partisan and biased. Most saying this seem to have little idea how the debate actually went!:

But that’s enough complaining about the commenters!

3 Matt’s confusion about fine-tuning

During the cross-examination period, Matt secreted more desperate and half-hearted objections to fine-tuning than a hagfish secretes slime.2 When I pointed out why these objections didn’t work, he would quickly move on to a different point without acknowledging that he was wrong about the first point. For example:

Matt: You could change things and have a different universe crop up where a different set of life forms would be considering how the universe was created for them.

…

Me: What are some of the examples of fine-tuning that are cited by theists … that if the constants were to be changed you think you could get a different kind of life like? For example, do you think that about the cosmological constant? Do you think that about the Higgs mass?

Matt: I have no idea I'm not even convinced that those things could [be different].

…

Me: If the cosmological constant were a little bit weaker… then much less than one millisecond after the big bang everything would have collapsed in on itself. If it were a little bit stronger everything would have flown apart much less than 1 millisecond after the big bang started. And… the only values of the cosmological constant that give rise to complex structures that don't result in everything imploding or in everything flying apart are values … that fall in a portion of the possible range that's about one part in 10 to the power of 120 of the values you could take on. So my question for you is this Matt: do you think that if everything flew apart after less than a millisecond that you could get a stable form of life?

Matt: I have no idea. That's not relevant and not my area of expertise. And the way that you're framing this is very problematic because I've already acknowledged that I'm not convinced those constants could have been any other way. But even let's imagine that there's a multiversal universe generator and it keeps popping out universes.

In the above clip, I pointed out that Matt’s claim that you could get life with different constants is totally ridiculous. If, for instance, the cosmological constant were a bit weaker or stronger, everything would either collapse or implode after less than a millisecond. Neither scenario seems particularly conducive to life. Matt—after admitting he had no idea which constants you could change while still having life—then slithered wormlike to begin talking about multiverses and various other objections. When he was proved wrong on a point, he simply hopped to a new one without acknowledging his error. This is profoundly intellectually dishonest. If you have no idea whether life could arise with different conditions, why the hell are you raising the objection to fine-tuning that life could arise under different conditions?

Matt gave other silly objections to fine-tuning. He said that fine-tuning can’t be evidence for theism because we couldn’t have found ourselves in a non-finely tuned universe. But that’s totally irrelevant! If a firing squad shoots their guns at you and they all—all hundred of them—miss, that’s evidence of a conspiracy. This is so even though in the absence of a conspiracy, you wouldn’t have been around to observe it. (After I pointed this out, predictably Matt hopped to a new point like a small child playing ‘the floor is lava’).

He additionally argued—as you can see in the above quote—that perhaps the constants couldn’t be different. Maybe the constants are necessary. But this is irrelevant. As I pointed out, if the initial conditions spelled out “made by God,” that would be strong evidence that there was a creator. One could similarly declare the initial conditions necessary in that case, but this wouldn’t blunt the surprisingness of the situation. As long as there’s no a priori reason to expect some outcome to turn out some specific way, merely building into your theory that the thing is necessary doesn’t help explain it.

Matt’s reply to the made by God case was to note that languages came about after the universe. While unlike most of what Matt said, this had the virtue of being true, it was totally irrelevant to the point being made. If merely declaring something potentially necessary means it’s no longer improbable then that would equally apply to initial conditions spelling out made by God.

4 Wackamole

Matt made a very great number of bizarre and badly confused claims. Most of these don’t take long to address.

Much of Matt’s opening statement was merely repeating that you need good evidence to reasonably believe something. I of course agree. But that does nothing to show that there is not reasonable evidence for theism.

Another large chunk of Matt’s opening statement involved conversationally implicating points without saying them explicitly. Then, when I explained why those points were wrong, he accused me of misrepresenting him. For instance, in his opening statement he made great hay over the fact that there wasn’t physical evidence for theism.

When I in response pointed out that there kind of was—in that there was evidence from physics—and we don’t need physical evidence to believe in some hypothesis, he accused me of misrepresenting him. We have no physical evidence that stars outside the known universe behave the same way stars in the known universe behave, but we should still obviously believe it.

Matt asked how one can differentiate between an all powerful being from a merely very powerful being. The answer: even if some very powerful beings behave like all-powerful beings, because all-powerful beings are simpler and less arbitrary, they’re much likelier. A limitless mind is simple—a mind with all sorts of arbitrary desires and powers is horrendously complicated.

Matt asked what it means to be all knowing. Answer: to be all knowing means to know every truth. For everything that is true, an all-knowing being knows it. That is why the word “all” comes in front of the word “knowing”—to denote that what one knows isn’t just some things, but everything!

Matt asked if God knows the future. I think he does, but that’s not relevant to the debate. It depends on whether there are true facts about the future. I think there are—in which case God knows them. If there aren’t then he doesn’t know it. This would be like asking whether God knows that Goldbach’s conjecture is true—I don’t know because I don’t know if it is true.

Matt asked how we know God is even possible. Now predictably he didn’t clarify what kind of possibility he was talking about. But as I noted in my opening statement, first proving stuff is possible is not how science works. It wasn’t first proved that dark matter was possible—whatever the hell it means to prove something is possible. Instead we assumed it was possible—and actual—because it explained the data so well. Same thing with Hannibal using elephants to cross the alps. Same thin with God.

Also, we generally assume things are possible by default. Unicorns aren’t real, but they are possible—at least in the broad logical sense. Unless there’s some hidden contradiction lurking within the definition of God, we should assume God’s existence is possible.

Matt then said that we should go with the “I don’t know” explanation over the God explanation. But this is just a baseless assertion. One can always appeal to an unknown explanation. But if a known explanation can explain many different lines of data, it’s obviously to be preferred. A Young Earth Creationist could similarly appeal to an unknown explanation of transitional fossils, atavisms, nested hierarchies, endogenous retroviruses, similar morphology, and so on, but this wouldn’t be rational!

Matt gave—at considerable length—an analogy about dice. If you came across two dice on a table, set to be 6s, their present state would be likelier if someone set them to come up 6. But you wouldn’t have justification to believe that. Thus, Matt’s conclusion: merely explaining some facts doesn’t make something worth believing.

Now, as stated, this is absolutely correct. Instead, a theory is reasonable to believe if it starts with a non-trivial prior and explains facts about the world well. Whether something is reasonable to believe is a function of the strength of the evidence AND its prior probability. Neither is sufficient, just as both the top blade and bottom blade are needed in a pair of scissors to cut stuff. Matt’s objection is analogous to noting that there are some cases where the top blade of scissors can’t cut stuff—and then concluding that some particular pair of scissors must be unable to cut. The fact that the strength of the Bayes factor is relevant is why if you saw 10 dice turned over—all set to 6—you’d be justified in assuming they were set and not rolled.

Matt asked why it’s good to create life. Answer: it’s good to exist and live a happy life. It’s good for me that my parents created me. Because an afterlife is likely given theism, conditional on theism it’s very likely a great number of people would be created. In addition, because the odds of people existing are so low on atheism, even if you don’t think the odds are very high on theism, such an occurrence is still clear evidence for theism. For more on why it’s good to create a person with a good life, see here.

Lastly, Matt noted that if you turn over a deck of cards, the particular sequence you get is inevitably very unlikely. The odds of getting that particular sequence are one in fifty-two factorial—which is more than the number of particles in the universe. He seemed to treat this as analogous to fine-tuning.

Reply: Pointing to random improbable events isn’t automatically evidence for a theory. It’s only evidence for the theory if the event is likelier given the theory than given the theories falsity. It’s no likelier God would rig the deck to get any particular outcome than that we’d get that outcome by chance.

Matt’s reply: But what about a God who specifically loves that sequence of cards. Wouldn’t there be lots of evidence for such a being?

My reply: Yep! But such a being has a very low prior. It’s true that if you see a deck turned over that goes Jack of hearts, ace of spades, jack of diamonds… that will raise the likelihood of there being someone who rigged the deck and prefers that particular sequence to any other. But the prior probability of there being a rigger who loved that particular sequence is very low. There’s a distinct possible rigger for every possible sequence of cards, so the prior probability of someone who rigs things to get that particular sequence is on the order of one in fifty-two factorial.

This is why if we see a deck of cards in some special order, we assume it was rigged. If the order is one of hearts, one of diamonds, one of spades, one of clubs, two of hearts… we assume that it was set up that way. While the probability that one would get that sequence by chance are just as low as the odds of getting any other sequence by chance, the odds of getting that sequence by non-chance are vastly higher.

Matt said made many more ridiculous and false things in the debate. If every one of them were written down, I suppose that even the whole world would not have room for the books that would be written.

5 New atheist anti-intellectualism

The new atheists—those of Dillahunty’s ilk—pride themselves on being champions of reason and science. But in reality, they champion reason about as much as Donald Trump champions a Catholic views of sexual ethics. They are RINOs—rational in name only.

They don’t think carefully before forming beliefs. They instinctively dismiss arguments for God without considering them carefully. They assume from the outset that belief in God must be like belief in Santa Claus, and then display seemingly invincible ignorance on the subject. While they endlessly crow about bias and fallacies, they are perhaps the single most vulnerable group to confirmation bias on the planet. They’re wholly and totally incapable of following a line of argument to its conclusion without hallucinating fallacious claims that bear no resemblance to the claims appearing in the argument.

When they get things wrong, they do not care. They rarely issue corrections. They make basic mathematical and scientific errors with impunity and don’t display one ounce of humility. While they occasionally say they don’t know something, they always do it with a triumphant sneer. They treat their own ignorance as a counterargument, not as a possibility for genuine exploration.

They call religious people irrational, while their epistemology is generally worse than the epistemology of Young Earth creationists. While they LARP a great deal about their love for truth and evidence, they’re among the least thoughtful and intellectually curious groups around. They betray their enlightenment forebearers.

Their wrong claims run the gamut from ones about science to history to philosophy. You won’t find a philosopher that takes seriously their contentious philosophical judgments nor a historian who takes seriously their historical judgments. While there are many smart and thoughtful atheists, the Dillahunty and Dillahunty fans of the world seem to avoid a genuine search for truth as vampires avoid the sun.

The situation regarding the new atheists is a rather curious one. The people who talk most about bias, evidence, and reason, are the least concerned about them. They treat with disdain those who would know more about philosophy of religion after a frontal lobotomy than the new atheist “intellectuals” ever will.

Many of the former new atheists have abandoned it. Sam Harris now seriously thinks about philosophy rather than engaging in the kind of hackish slapdash drive-by of the new atheists when I was growing up. Alex O’Connor—whom I met recently—is a serious heavy-hitter on both historical topics and philosophy of religion. Gone is the naive high school student who thought belief in God is like belief in Santa—in is a real intellectual.

But some like Dillahunty haven’t gotten the memo. They continue to treat theism with disdain, continue to overconfidently and zealously declare that belief in God is absurd. They continue to act like they know everything while badmouthing those who disagree with them. They remain locked in a kind of shallow dogmatism where they’re unable to consider the possibility that anyone might have reason for rejecting their view.

It’s a rather sad situation. We should all pray for them!

Provided the prior is not zero, which it wasn’t in the scenario described.

(I heard this line somewhere and thought it was funny but couldn’t remember where).

"A limitless mind is simple—a mind with all sorts of arbitrary desires and powers is horrendously complicated".

I don't understand why you think we can just assume this. You seem to think a limitless mind is simple just because you can explain it in a few words. In truth we have no idea what a limitless mind would look like and it is likely that any set of laws that could allow such a mind to exist in a given realm would be extremely complicated.

By contrast, we can be pretty certain that merely powerful (not omniscient) minds are possible under the same physical laws in our universe. Given stuff like the problem of evil, wouldn't it make way more sense if God was extremely powerful but not infinitely so? And that he tried to make a universe with lots of conscious, happy entities but did not fully realize that vision?

‘New Atheists’ aren’t really against Theism,but against Christianity,it’s why Dillahunty’s commenters were mocking virgin birth,YEC,etc. in the live chat instead of engaging with your arguments. Their self assurance comes from their confidence in Christianity’s falsehood,particularly fundamentalist / Calvinist (Baptist) Christianity (which I’m nearly certain is true)

I think it would do you a lot better to elaborate on your view of god instead of your argument for god in debates with non-intellectuals & their fans,who would then be more open to hearing you out