See here for part 1

A Bayesian Analysis Of When Utilitarianism Diverges From Our Intuitions

Why we shouldn't worry too much about the cases in which utilitarianism goes against our intuitions

“P(B)|A=P(B)xP(A)|B/P(A)”

—Words to live by

Lots of objections to utilitarianism, like the problem of measuring utility, rest on conceptual confusions. However, of the ones that don’t rest on basic conceptual confusions, most of them rely on the notion that utilitarianism is unintuitive. Utilitarianism entails the desirability of organ harvesting, yet some people have strange intuitions that oppose killing people and harvesting their organs (I’ll never understand such nonsense!).

In this post, I will lay out some broad considerations about utilitarianisms’ divergence from our intuitions and explain why these are not very good evidence against utilitarianism.

The fact that there are lots of cases where utilitarianism diverges from our intuitions is not surprising on the hypothesis that utilitarianism were correct. This is for two reasons.

There are enormous numbers of possible moral scenarios. Thus, even if the correct moral view corresponds to our intuitions in 99.99% of cases, it still wouldn’t be too hard to find a bunch of cases in which the correct view doesn’t correspond to our intuitions.

Our moral intuitions are often wrong. They’re frequently affected by unreliable emotional processes. Additionally, we know from history that most people have had moral views we currently regard as horrendous.

Because of these two factors, our moral intuitions are likely to diverge from the correct morality in lots of cases. The probability that the correct morality would always agree with our intuitions is vanishingly small. Thus, given that this is what we’d expect of the correct moral view, the fact that utilitarianism diverges from our moral intuitions frequently isn’t evidence against utilitarianism. To see if they give any evidence against utilitarianism, let’s consider some features of the correct moral view, that we’d expect to see.

The correct view would likely be able to be proved from lots of independent plausible axioms. This is true of utilitarianism.

We’d expect the correct view to make moral predictions far ahead of its time—like for example discerning the permissibility of homosexuality in the 1700s.

While our intuitions would diverge from the correct view in a lot of cases, we’d expect careful reflection about those cases to reveal that the judgments given by the correct moral theory to be hard to resist without serious theoretical cost. We’ve seen this over and over again with utilitarianism, with the repugnant conclusion , torture vs dust specks , headaches vs human lives, the utility monster, judgments about the far future, organ harvesting cases and other cases involving rights, and cases involving egalitarianism. This is very good evidence for utilitarianism. We’d expect incorrect theories to diverge from our intuitions, but we wouldn’t expect careful reflection to lead to the discovery of compelling arguments for accepting the judgments of the incorrect theory. Thus, we’d expect the correct theory to be able to marshal a variety of considerations favoring their judgments, rather than just biting the bullet. That’s exactly what we see when it comes to utilitarianism.

We’d expect the correct theory to do better in terms of theoretical virtues, which is exactly what we find.

We’d expect the correct theory to be consistent across cases, while other theories have to make post hoc changes to the theory to escape problematic implications—which is exactly what we see.

There are also some things we’d expect to be true of the cases where the correct moral view diverges from our intuitions. Given that in those cases our intuitions would be making mistakes, we’d expect there to be some features of those cases which make our intuitions likely to be wrong. There are several of those in the case of utilitarianism’s divergence from our intuitions.

A) Our judgments are often deeply affected by emotional bias

B) Our judgments about the morality of an act often overlap with other morally laden features of a situation. For example, in the case of the organ harvesting case, it’s very plausible that lots of our judgment relates to the intuition that the doctor is vicious—this undermines the reliability of our judgment of the act.

C) Anti utilitarian judgments get lots of weird results and frequently run into paradoxes. This is more evidence that they’re just rationalizations of unreflective seemings, rather than robust reflective judgment.

D) Lots of the cases where our intuitions lead us astray involve cases in which a moral heuristic has an exception. For example, in the organ harvesting case, the heuristic “Don’t kill people,” has a rare exception. Our intuitions formed by reflecting on the general rule against murder will thus be likely to be unreliable.

Conclusions

Suppose we had a device that had a 90% accuracy rate in terms of identifying the correct answer to math problems. Then, suppose we were deciding whether the correct way to solve a math problem was to use equation 1 or equation 2. We use the first equation to solve 100 math problems, and the result is the same as the one given by the device 88 times. We then use equation 2 and find the results correspond with those given by the device in all 100 cases.

We know one of them has to be wrong, so we look more carefully. We see that the 12 cases in which the first equation gets a result different from that of the second equation are really complex cases in which the general rules seem to have exceptions—so they’re the type of cases in which we’d expect the equation that’s merely a heuristic to get the wrong result. We also look at both of the equations and find that the first equation has much more plausibility, it seems much more like the type of equation that would be expected to be correct.

Additionally, the second equation has lots of subjectivity—some of the values for the constants are chosen by the person applying it. Thus, there’s some room for getting the wrong result based on bias and the assumptions of the person applying it.

We then see a few plausible seeming proofs of the first equation and see that the second equation isn’t able to make sense of lots of different math problems, so it has to attach auxiliary methods to solve those. We then hear that previous students who have used the first equation have been able to solve very difficult math problems—ones that the vast majority of people (most of whom use the second equation), have almost universally gotten wrong. We also see that equation 2 results in lots of paradoxical seeming judgments—we have to call in our professional mathematician friend (coincidentally named Michael Huemer) to find a way to make them not straightforwardly paradoxical, and the judgment he arrives at requires lots of implausible stipulations to rescue equation 2 from paradox. Finally, we find that in all 12 of the cases in which the correct answer diverges from the answer given by the device, there are independent pretty plausible proofs of the results gotten by equation 1 and they’re more difficult problems—the type that we’d expect the device to be less likely to get right.

In this case, it’s safe to say that equation 1 would be the equation that we should go with. While it sometimes gets results that we have good reason to prima facie distrust (because they diverge from the method that’s accurate 90% of the time), that’s exactly what we would expect if it were correct, which means all things considered, that’s not evidence against it. Additionally, the rational judgment in this case would be that equation 2—like many moral systems—is just an attempt to mirror our starting beliefs, rather than to figure out the right answer, forcing revision of our beliefs.

Our moral intuitions are the same—they’re right most of the time, but on the hypothesis that they’re usually right, we’d still expect there to be lots of cases in which our moral intuitions are wrong. When we carefully reflect on the things we’d expect if utilitarianism were correct, they tend to match exactly what we see.

Torres Is Wrong About Longtermism

Very, very wrong

Phil Torres has written an article criticizing longtermism. Like most articles criticizing longtermism, it does so very poorly, making arguments that rely on some combination of question begging and conceptual confusion. One impressive feature of the article is that the cover image managed to make Nick Bostrom and Will MacAskill look intimidating—so props for that I guess.

So-called rationalists have created a disturbing secular religion that looks like it addresses humanity’s deepest problems, but actually justifies pursuing the social preferences of elites.

This is the article’s subtitle. Lets see if throughout the article Torres is able to substantiate such claims.

The religion claim is particularly absurd. Religion in such contexts is just used as a term of abuse—it has no meaning beyond “X is a group that is doing things, that we don’t like.” As Huemer points out, to be a religion an organization needs to have many of the following: faith, supernaturalism, a worldview, a source of meaning, self support, religious emotions, ingroup identification, source of identity, and organization. Longtermism has very few of these—far fewer than the democratic party.

I won’t quote Torres’ full article for word count purposes—I’ll just quote the relevant parts.

In a late-2020 interview with CNBC, Skype cofounder Jaan Tallinn made a perplexing statement. “Climate change,” he said, “is not going to be an existential risk unless there’s a runaway scenario.”

So why does Tallinn think that climate change isn’t an existential risk? Intuitively, if anything should count as an existential risk it’s climate change, right?

Cynical readers might suspect that, given Tallinn’s immense fortune of an estimated $900 million, this might be just another case of a super-wealthy tech guy dismissing or minimizing threats that probably won’t directly harm him personally. Despite being disproportionately responsible for the climate catastrophe, the super-rich will be the least affected by it.

But I think there’s a deeper reason for Tallinn’s comments. It concerns an increasingly influential moral worldview called longtermism.

The reason Tallinn thinks climate change isn’t an existential risk is because climate change isn’t an existential risk—at least not a significant one. To quote FLI

An existential risk is any risk that has the potential to eliminate all of humanity or, at the very least, kill large swaths of the global population, leaving the survivors without sufficient means to rebuild society to current standards of living.

Global warming is likely to be very bad, but will not achieve that. It is thus not an existential risk. This is not to downplay it—crime, disease, and poverty are all also very bad but not existential risks. Thus, Torres’ first objection can be summarized as.

Premise 1: Longtermism claims that climate change isn’t an existential risk absent a runaway scenario

Premise 2: Climate change is an existential risk absent a runaway scenario

Therefore, longtermism is wrong.

However, both premises are suspect. Finding one longtermist saying a statement doesn’t mean it’s the position accepted by all. I accept climate change will likely increase international instability, leading to some greater existential risks, even absent cataclysm. However, it is not likely to end the world absent a runaway scenario.

Next, Torres says

At the heart of this worldview, as delineated by Bostrom, is the idea that what matters most is for “Earth-originating intelligent life” to fulfill its potential in the cosmos. What exactly is “our potential”? As I have noted elsewhere, it involves subjugating nature, maximizing economic productivity, replacing humanity with a superior “posthuman” species, colonizing the universe, and ultimately creating an unfathomably huge population of conscious beings living what Bostrom describes as “rich and happy lives” inside high-resolution computer simulations.

The points about space colonization are wrong. A vast number of beings living rich and happy lives would be good—happiness is good, so unfathomable happiness would be unfathomably good. Torres concerns about space colonization have been devastatingly taken down here. Putting rich and happy lives in scare quotes doesn’t undermine the greatness of rich and happy lives—ones unfathomably better than any we can currently imagine.

An existential risk, then, is any event that would destroy this “vast and glorious” potential, as Toby Ord, a philosopher at the Future of Humanity Institute, writes in his 2020 book The Precipice, which draws heavily from earlier work in outlining the longtermist paradigm.

Torres has correctly described existential risks.

The point is that when one takes the cosmic view, it becomes clear that our civilization could persist for an incredibly long time and there could come to be an unfathomably large number of people in the future. Longtermists thus reason that the far future could contain way more value than exists today, or has existed so far in human history, which stretches back some 300,000 years. So, imagine a situation in which you could either lift 1 billion present people out of extreme poverty or benefit 0.00000000001 percent of the 10^23 biological humans who Bostrom calculates could exist if we were to colonize our cosmic neighborhood, the Virgo Supercluster. Which option should you pick? For longtermists, the answer is obvious: you should pick the latter. Why? Well, just crunch the numbers: 0.00000000001 percent of 10^23 people is 10 billion people, which is ten times greater than 1 billion people. This means that if you want to do the most good, you should focus on these far-future people rather than on helping those in extreme poverty today. As the FHI longtermists Hilary Greaves and Will MacAskill—the latter of whom is said to have cofounded the Effective Altruism movement with Toby Ord—write, “for the purposes of evaluating actions, we can in the first instance often simply ignore all the effects contained in the first 100 (or even 1,000) years, focussing primarily on the further-future effects. Short-run effects act as little more than tie-breakers.”

A few points are worth making.

The correct view will often go against our intuitions. Pointing out that this seems weird isn’t especially relevant.

The ratio of future to current humans is greater than 1 trillion to one, if we accept Bostrom’s assumptions. If there were 2 people and they knew that whether 2 trillion people existed depended on what they did, it would seem pretty intuitive that their primarily obligation would be making sure the 2 trillion people had good lives. Presentism and status quo bias combined with our inability to reason about large numbers undermine our intuitions here.

The way to improve the future is often to improve the present. A world with war, poverty, disease, and violence will be worse at solving existential threats.

This brings us back to climate change, which is expected to cause serious harms over precisely this time period: the next few decades and centuries. If what matters most is the very far future—thousands, millions, billions, and trillions of years from now—then climate change isn’t going to be high up on the list of global priorities unless there’s a runaway scenario.

This is true, yet hard to see from our present location. Let’s consider past historical events to see if this is really unintuitive when considered rationally. The black plague very plausibly lead to the end of feudalism. Let’s stipulate that absent the black plague, feudalism would still be the dominant system, and the average income for the world would be 1% of what it currently is. Average lifespan would be half of what it currently is. In such a scenario, it seems obvious that the world is better because of the black plague. It wouldn’t have seemed that way to people living through it, however, because it’s hard to see from the perspective of the future.

In the same paper, Bostrom declares that even “a non-existential disaster causing the breakdown of global civilization is, from the perspective of humanity as a whole, a potentially recoverable setback,” describing this as “a giant massacre for man, a small misstep for mankind.” That’s of course cold comfort for those in the crosshairs of climate change—the residents of the Maldives who will lose their homeland, the South Asians facing lethal heat waves above the 95-degree F wet-bulb threshold of survivability, and the 18 million people in Bangladesh who may be displaced by 2050. But, once again, when these losses are juxtaposed with the apparent immensity of our longterm “potential,” this suffering will hardly be a footnote to a footnote within humanity’s epic biography.

Several facts are worth noting.

EA’s are working on combatting climate change, largely for the reasons Torres describes.

There are robust philosophical arguments for caring overwhelmingly about the far future. Just because they don’t exist yet doesn’t mean they shouldn’t factor into our moral consideration. This preference is as irrational as the preference for those who are close geographically, over those who are far away.

Consider one such argument. (Note, I’ll use utility, happiness, and well-being interchangeably and disutility, suffering, and unpleasantness interchangeably).

1 It is morally better to create a person with 100 units of utility than one with 50. This seems obvious—pressing a button that would make your child only half as happy would be morally bad.

2 Creating a person with 150 units of utility and 40 units of suffering is better than creating a person with 100 units of utility and no suffering. After all, the one person is better off and no one is worse off. This follows from a few steps.

A) The expected value of creating a person with utility of 100 is greater than of creating one with utility zero.

B) The expected value of creating one person with utility zero is the same as the expected value of creating no one. One with utility zero has no value or disvalue to their life—they have no valenced mental states.

C) Thus, the expected value of creating a person with utility of 100 is positive.

D) If you are going to create a person with a utility of 100, it is good to increase their utility by 50 at the cost of 40 units of suffering. After all, 1 unit of suffering’s badness is equal to the goodness of 1 unit of utility, so they are made better off. They would rationally prefer 150 units of utility and 40 units of suffering to 100 units of utility and no suffering.

E) If one action is good and another action is good given the first action, then the conjunction of those actions is good.

These are sufficient to prove the conclusion. After all, C shows that creating a person with a utility of 100 is good, D shows that creating a person with utility of 150 and 40 units of suffering is better than that, so from E, creating a person with utility of 150 and 40 units of suffering is good.

This broadly establishes the logic for caring overwhelmingly about the future. If creating a person with any positive utility and no negative utility is good, and then increasing their utility and disutility by any amount, such that their positive utility increases more than their disutility does, is good, then you should create a person if their net utility is positive. This shows that creating a person with 50 units of utility and 49.9 units of disutility would be good. After all, creating a person with .05 units of utility would be good, and increasing their utility by 49.95 at the cost of 49 units of disutility would also be good, then creating a person with 50 units of utility is good. Thus, the moral value of increasing the utility of a future person by N is greater than the moral disvalue of increasing the disutility of a future person by any amount less than N.

Now, let’s add one more stipulation. The moral value of causing M units of suffering to a current person is equal to that of causing a future person M units of suffering. This is very intuitive. When someone lives shouldn’t affect how bad it is to make them suffer. If you could either torture a current person or a future person, it wouldn’t be better to torture the future person merely in virtue of the date of their birth. Landmines don’t get less bad the longer they’re in the ground.

From these we can get our proof that we should care overwhelmingly about the future. We’ve established that increasing the utility of a future person by N is better than preventing any amount of disutility for future people of less than N and that preventing M units of disutility for future people is just as good as preventing M units of disutility for current people. This would mean that increasing the utility of a future person by N is better than preventing any amount of disutility of current people of less than N. Thus, bringing about a person with utility of 50 is morally better than preventing a current person from enduring 48 units of suffering, by transitivity.

The common trite that it’s only good to make people happy, not to make happy people is false. This can be shown in two ways.

It would imply that creating a person with a great life would be morally equal to creating a person with a mediocre life. This would imply that if given the choice between bringing about a future person with utility of 5 and no suffering or a future person with utility of 50,000 and no suffering, one should flip a coin.

It would say (ironically given Torres’ pitch) that we shouldn’t care about the impacts of our climate actions on future people. For people who won’t be born yet, climate action will certainly change whether or not they exist. If a climate action changes when people have sex by even one second, it will change the identities of the future people that will exist. Thus, when we decide to take climate action that will help the future, we don’t make the future people better off. Instead, we make different future people who will be better off than the alternative batch of future people would have been. If we shouldn’t care about making happy people, then there’s no reason to take climate action for the future.

These aren’t the only incendiary remarks from Bostrom, the Father of Longtermism. In a paper that founded one half of longtermist research program, he characterizes the most devastating disasters throughout human history, such as the two World Wars (including the Holocaust), Black Death, 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, major earthquakes, large volcanic eruptions, and so on, as “mere ripples” when viewed from “the perspective of humankind as a whole.” As he writes:

“Tragic as such events are to the people immediately affected, in the big picture of things … even the worst of these catastrophes are mere ripples on the surface of the great sea of life.”

In other words, 40 million civilian deaths during WWII was awful, we can all agree about that. But think about this in terms of the 1058 simulated people who could someday exist in computer simulations if we colonize space. It would require trillions and trillions and trillions of WWIIs one after another to even approach the loss of these unborn people if an existential catastrophe were to happen. This is the case even on the lower estimates of how many future people there could be. Take Greaves and MacAskill’s figure of 1018 expected biological and digital beings on Earth alone (meaning that we don’t colonize space). That’s still a way bigger number than 40 million—analogous to a single grain of sand next to Mount Everest.

This is true. It is only unintuitive if one considers things from their own perspective rather than from the standpoint of humanity broadly. When considered from the perspective of humanity broadly, it becomes clear that our impacts on whether we go extinct have a bigger impact on the future than the first humans’ actions had on us up until that point. It seems pretty intuitive that the first humans should have avoided getting wiped out, even if they didn’t desire to do so, given the vast positive potential of civilization.

If pushed, the first would save the lives of 1 million living, breathing, actual people. The second would increase the probability that 10^14 currently unborn people come into existence in the far future by a teeny-tiny amount. Because, on their longtermist view, there is no fundamental moral difference between saving actual people and bringing new people into existence, these options are morally equivalent. In other words, they’d have to flip a coin to decide which button to push. (Would you? I certainly hope not.) In Bostrom’s example, the morally right thing is obviously to sacrifice billions of living human beings for the sake of even tinier reductions in existential risk, assuming a minuscule 1 percent chance of a larger future population: 10^54 people.

Torres just goes on and on about how unintuitive this is, without giving any arguments against it. Remember: we are but the tiniest specks from the standpoint of humanity. If humanity were a person’s lifetime, we wouldn’t even be the first hour. So, much like it makes sense to plan for the future—to delay an hour to reduce risk of dying by a small amount, it makes sense to undergo sacrifices (if they were necessary to reduce existential risks, which they aren’t really!) to improve the quality of the future.

Additionally, even if one is a neartermist, they should still be largely on board with reducing existential threats. Ord argues in his book risk of extinction is 1 in 6, Bostrom concludes risks are above 25%, Leslie concludes they’re 30%, Rees says they’re 50%. Even if they’re only 1%—a dramatic underestimate, that still means existential risks will in expectation kill 79 million people, many times more than the holocaust. Thus, existential risks are still terrible if one is a neartermist, so Torres should still be on board with the project.

If this sounds appalling, it’s because it is appalling. By reducing morality to an abstract numbers game, and by declaring that what’s most important is fulfilling “our potential” by becoming simulated posthumans among the stars, longtermists not only trivialize past atrocities like WWII (and the Holocaust) but give themselves a “moral excuse” to dismiss or minimize comparable atrocities in the future.

Longtermists don’t dismiss such attrocities. We merely say that the future is overwhelmingly important. Pointing out that there are things that are much bigger than earth doesn’t dismiss the size of the earth—it just points out that there are other things that are bigger.

If future people matter at all—even if their well-being matters only .001% as much as current people, the far future would still dominate our moral considerations. We live in a morally weird world—one which makes our intuitions often unreliable. If our intuitions lead to the conclusion that we should ignore the billions of years of potential humans, in favor of caring about what affects current people only, then are intuitions have gone wrong. It would be awfully suspicious if the correct morality happened to justify caring unfathomably more about what happens in the 21st century than in the 22nd, 23rd, 24th…through the 10 billionth century.

Torres has no argument against this thesis—all he has is a series of cantankerous squawks of outrage. His intuitions are not surprising and unlikely to be truth tracking. American’s care much more about American domestic policy, even though America’s effect on other countries is much more significant than the impact of our policies domestically. Given that we cannot talk to future people, it’s very easy to prioritize visible suffering. This is, however, unwise. There is no way to design a successful version of population ethics that does not care about the existence of 10^52 future people with excellent lives.

EA’s don’t dismiss attrocities in the future. Every single historical atrocity has come from excluding beings from our moral circle. Caring about everyone is what has prevented atrocities—not ignoring 10^52 possible sentient beings. Utilitarians like Bentham and Mill have tended to be opposed to such attrocities. Bentham supported homosexuality in the 1700s. Thus, it’s Torres’ non utilitarian nonsense—one which goes against every plausible view of population ethics—that is at the root of historical evils.

. This is one reason that I’ve come to see longtermism as an immensely dangerous ideology. It is, indeed, akin to a secular religion built around the worship of “future value,” complete with its own “secularised doctrine of salvation,” as the Future of Humanity Institute historian Thomas Moynihan approvingly writes in his book X-Risk. The popularity of this religion among wealthy people in the West—especially the socioeconomic elite—makes sense because it tells them exactly what they want to hear: not only are you ethically excused from worrying too much about sub-existential threats like non-runaway climate change and global poverty, but you are actually a morally better person for focusing instead on more important things—risk that could permanently destroy “our potential” as a species of Earth-originating intelligent life.

Several points are worth making.

If people were looking for a philosophical excuse for not helping others, they’d choose objectivism. What type of person wants to take action on reducing existential threats, so they come up with a philosophical rationalization to justify that. People want to justify inaction—not action on a weird issue relating to the far future.

Longtermism is largely part of EA—a movement specifically build around using resources to do as much good as we can. One has to be delusional to think Ord or MacAskill is using longtermism as an excuse for not helping others, particularly when they donate all above roughly 35,000 dollars per year.

Even if one only cares about current people, reducing existential risks is still overwhelmingly important.

Calling it a religion is not an argument—it’s just invective.

To drive home the point, consider an argument from the longtermist Nick Beckstead, who has overseen tens of millions of dollars in funding for the Future of Humanity Institute. Since shaping the far future “over the coming millions, billions, and trillions of years” is of “overwhelming importance,” he claims, we should actually care more about people in rich countries than poor countries. This comes from a 2013 PhD dissertation that Ord describes as “one of the best texts on existential risk,” and it’s cited on numerous Effective Altruist websites, including some hosted by the Centre for Effective Altruism, which shares office space in Oxford with the Future of Humanity Institute. The passage is worth quoting in full:

Notice, there is no argument given by Torres against this conclusion. He just complains about unintuitive conclusions—particularly those that run afoul of social justice taboos, rather than offering real arguments. I’ve argued against Torres’ view here.

Additionally, EA’s actions on global health and development are entirely about improving the quality of life in poor countries. Thus, even if saving the life of a person in a rich country is intrinsically more important than saving the life of a person in a poor country, the best actions to take in terms of saving lives in the short term will be about saving lives in poor countries.

Never mind the fact that many countries in the Global South are relatively poor precisely because of the long and sordid histories of Western colonialism, imperialism, exploitation, political meddling, pollution, and so on. What hangs in the balance is astronomical amounts of “value.” What shouldn’t we do to achieve this magnificent end? Why not prioritize lives in rich countries over those in poor countries, even if gross historical injustices remain inadequately addressed? Beckstead isn’t the only longtermist who’s explicitly endorsed this view, either. As Hilary Greaves states in a 2020 interview with Theron Pummer, who co-edited the book Effective Altruism with her, if one’s “aim is doing the most good, improving the world by the most that I can,” then although “there’s a clear place for transferring resources from the affluent Western world to the global poor … longtermist thought suggests that something else may be better still.”

Torres pointing out irrelevant historical facts and putting scare quotes around value is, once again, not an argument. The Pummer quote describes why longermists should focus mostly on longtermist thing, rather than combatting global poverty, which is plausible even if we accept short termism. Thus, Torres lies about what Pummer believes. He additionally fails to pinpoint any action being done towards this end that he’d actually disagree with.

The reference to AI, or “artificial intelligence,” here is important. Not only do many longtermists believe that superintelligent machines pose the greatest single hazard to human survival, but they seem convinced that if humanity were to create a “friendly” superintelligence whose goals are properly “aligned” with our “human goals,” then a new Utopian age of unprecedented security and flourishing would suddenly commence. This eschatological vision is sometimes associated with the “Singularity,” made famous by futurists like Ray Kurzweil, which critics have facetiously dubbed the “techno-rapture” or “rapture of the nerds” because of its obvious similarities to the Christian dispensationalist notion of the Rapture, when Jesus will swoop down to gather every believer on Earth and carry them back to heaven. As Bostrom writes in his Musk-endorsed book Superintelligence, not only would the various existential risks posed by nature, such as asteroid impacts and supervolcanic eruptions, “be virtually eliminated,” but a friendly superintelligence “would also eliminate or reduce many anthropogenic risks” like climate change. “One might believe,” he writes elsewhere, that “the new civilization would [thus] have vastly improved survival prospects since it would be guided by superintelligent foresight and planning.”

Once again Torres has no argument—he just has slogans. Nothing that he has said should change anyone’s assessment of AI existential risks. The experts who have considered the issue rather than sneering at it tend to be pretty worried.

Torres’ article levies bad critiques, takes things out of context from hundred page books, and flagrantly misrepresents many points. It is not a serious objection to longtermism.

Addressing A Bad Objection To Utilitarianism

Yes, we can compare utility--even interpersonally.

One common yet poor objection to utilitarianism claims we cannot make interpersonal comparisons of utility so utilitarianism fails. It relies on an unmeasurable metric. This objection is nonsense.

For one, we frequently do make interpersonal comparisons of utility. We often make judgments that people tend to be worse off when they’re in poverty, subject to bombing, and when affected by pollution. Being precise about such matters poses difficult empirical questions, but interpersonal comparisons of utility are required in all political decisions.

If our set of values is to be consistent, we need to have a coherent utility function. If one adopts a view that one person in poverty is less bad than a person who is dead, but they do not give a number of people in poverty with equal moral weight to one person being dead, their view runs into a problem. Suppose one has the ability to either lift twenty people out of poverty or to prevent one death. In that situation, they have to come to a decision about whether preventing a death is more important than pulling twenty people out of poverty. If they would rather prevent the one death, then their utility function values preventing a single death more than pulling twenty people out of poverty. If they’d rather prevent twenty people from being put into poverty, the opposite would be true. If their answer is one of neutrality, then they would be indifferent between those two options. However, if their view is neutral between those two then they must judge preventing twenty-one people from being in poverty as more important than preventing one death. If they remain indifferent even in the case of twenty-one people, then they judge preventing twenty people from being in poverty to be morally equivalent to preventing one death, which they judge to be morally equivalent to preventing twenty people from being put into poverty. Thus, by transitivity, they’d be indifferent between twenty-one people being in poverty and twenty being in poverty. This is an implausible view.

As has been well documented by economists, as long as one’s judgments meet certain minimal standards for rationality, it must be able to be modeled as optimizing for some utility function. Thus, in order for a moral system to be robustly rational, it must make certain judgments about utility. If other moral systems cannot be modeled as a utility function, that means they are false.

To see this with a simple example, it is clear that setting one on fire is considerably morally worse than shoving someone. However, it is not infinitely worse. A coherent utility function would have a ratio of disutility caused by setting someone on fire to shoving someone of N, where they’d be indifferent between a 1/N chance of setting someone on fire and a certainty of shoving someone.

Additionally, given that utility here describes a type of mental state, there’s nothing problematic about making interpersonal comparisons of utility. Much like it would be possible in theory to judge whether or not a particular action increases the total worldwide experience of the color red, the same is true of utility. A way to conceptualize the metric is to imagine oneself as if they experienced every single thing that will be experienced by anyone and then act as if you were maximizing the expected quality of your experiences.

When it is conceptualized this way, it is evidently conceptually coherent. Judgments of the collective experience are logically no different from judgments of one's own experience. People very frequently make judgments about whether or not particular actions would increase their own happiness--for example when they decide upon a job, college, or choice of vehicle.

Additionally, every plausible theory will hold that the considerations of utilitarianism are true, except in particular cases. Every plausible moral view holds, for example, that if you could benefit one of two people of similar moral character, and you could benefit one of them more than the other, you should benefit the one that you could benefit more. Thus, issues surrounding evaluating consequences would plague all plausible moral theories.

Lots Of Bad Things Are Like Drunk Driving

Clearing up a confusion about utilitarianism

Content Warning: Sexual Assault

Consider the question: is drunk driving always bad? In a trivial sense—no, there have no doubt been some cases in history in which a person was slightly drunk but needed to drive to, for example, rush a wounded person to a near-bye hospital. However, this question is really asking about negligent drunk driving, where someone drives drunk for no greater purpose, posing significant risks.

In this case, there seems to be a clear distinction that needs to be made between being bad and being wrong. Drunk driving for trivial gains is always wrong, it poses dramatic risks for little benefit. However, drunk driving isn’t always bad—if it harms no one then it was an unnecessary risk, but it ended up not being bad.

Thus, we need to be clear about the distinction between badness and wrongness. An action can be called wrong if it shouldn’t have been done by the agent, knowing what they knew at the time. On the other hand, an action is bad if it ends up causing more harm than benefits, such that it would be better for it never to have taken place. Hitler’s grandmother having sex was bad, but it wasn’t necessarily wrong.

With this distinction in place, many of the counterexamples to utilitarianism end up dissipating. Worries that utilitarianism says that attempted murders that fail aren’t necessarily wrong are false, when wrongness is understood this way. It could turn out that they might not end up being bad. However, they are always bad in expectation, such that they’re the type of thing that ought not be done. Oftentimes, our judgments going against utilitarianism rely on oversimplifications of the real world, such that we imagine a more realistic real world stand in, in place of the bizarre stipulations of the hypothetical.

Consider the case of the sexual abuse of a comatose patient who will never find out. In any realistic situation, there will always be some risk that the person will be harmed. First of all, there’s a high chance that you will be discovered sexually assaulting them. To rule this out, god himself would have to appear to you and guarantee that you won’t be found out. Second, there’s a high chance of inducing pregnancy or spreading an STD. Thus, there needs to be some 100% safe method of having sex that leaves no risk of any harm. Third, there must be total certainty that the person will never find out. Fourth, there must be a guarantee that it won’t have any negative effect on your character—something that would never be true in a realistic situation. Realistically, sexually assaulting a comatose patient would make someone a worse person. Fifth, there must be some absolute guarantee that you will never feel guilty about it. Sixth, there must be some absolute guarantee that violating the norms against such acts in this case won’t spill over to other acts. Seventh, there must be a guarantee that the subjective experience of every single person except you will be no different if you take the act—so no else’s mental states will be any different. In such a bizarre case that involves divine revelation, the absolution of guilt or other negative character effects, and many others—would we really expect our intuitions to translate over? Especially because taking such an act would be clear evidence of vicious character—something our moral intuitions tend to find objectionable.

This case is thus much like the drunk driving case. Drunk driving is wrong because it’s harmful in expectation—you shouldn’t do it. However, if we somehow stipulate with metaphysical certainty that no one will be harmed by your drunk driving, then it becomes not objectionable. The act will still be morally wrong in any realistic situation—it just may not end up being bad. To be bad, it must be bad for someone.

To show the intuition, imagine if every second aliens were constantly sexually assaulting all humans, in ways that the humans never found out about. The aliens committed about 100^100^100 sexual assaults per second. In the absence of any sexual assault, the aliens would subjectively experience the sum total of all misery experienced during the holocaust every single second. However, each assault (which no one ever finds out about) reduces their misery by a tiny amount, such that if they commit the 100^100^100 assaults per second, their subjective experience will be equivalent to the sum total of all human happiness ever experienced, experienced every second. In this case, the marginal utility from each assault is very small. Yet it seems quite intuitive that the aliens’ actions would be permissible. When it’s sufficiently divorced from the real world that we understand clearly the ways in which the act is optimific, it becomes quite clear that the act can be, in certain bizarre counterfactual cases, permissible.

Thus, we need to be much clearer when conceptualizing thought experiments. Sometimes bad things aren’t wrong and wrong things aren’t bad. When we mix those up, we get false beliefs and confusion. Lots of wrong things end up not being bad—in most cases drunk driving probably doesn’t cause harm, but it still shouldn’t be done, because it causes harm in expectation.

Utilitarianism Wins Outright Part 26

A Sidgwick Inspired Proof

Suppose we accept the following principles.

Morality describes what we’d do if we were fully rational and impartial.

If we were fully rational we’d regard all moments of existence as equal, independently of when they occur.

If we were fully impartial, we’d regard benefits for all beings as equally important intrinsically

If we were fully rational and impartial we’d only care about things that make beings better off.

Only desirable mental states make people better off.

These are sufficient to derive utilitarianism. If we should only care about mental states, care about all mental states equally, care about all people equally, and maximize desirable mental states, that is just utilitarianism.

Premise 1 was defended here.

Premises 2 and 3 were defended extensively by (Singer and Lazari-Radek, 2014). Premises 4 and 5 were defended in here and here.

Premise 2 seems to follow straightforwardly from rationality. If one is rational, they wouldn’t regard the time in which an event happens as significant to how good it is. We think it foolish, for example, to procrastinate, ignore one's pains on a future tuesday merely in virtue of it being tuesday, and in other ways care about the time in which particular actions take place.

(Williams, 1976, p.206-209) objects to this notion, writing

“The correct perspective on one's life is from now.”

Williams claims that it’s rational to do what we currently desire to do, regardless of whether it would harm us later. However, as (Singer and Lazari-Radek, 2014) potently object, this would lead to it being possible for one to make fully rational decisions that they predict they will regret, ones that artificially discount the future. This seems absurd. Similarly, if a person endures infinite suffering tomorrow to avoid a pinprick now, that seems clearly irrational.

Singer and Lazari-Radek go on to describe another view, according to which the end of one's life matters more, espoused by many. This argument usually involves appealing to the intuition that it’s worse for a life to start out good but then end bad than for the opposite to occur, even if the lives are equally good. They argue against this intuition, pointing out that one primary reason this seems the case is that a life that starts out good before turning bad will in general be a worse life. The people will, in their old age, be disappointed about all that they’ve lost. However, if we stipulate that the quality of life is exactly identical, it becomes harder to maintain.

Several other objections can be given to this view. One of them is that it results in strange moral implications of when people are born. Suppose that one is born with memories of the end of their life, but in the end of their life they lose their memories of earlier parts of their life. In that case, it seems like the earlier part of their life is more important, because in that part they remember life being unpleasant and appreciate the improvement. The point in time at which their life takes a turn for the better seems less important than facts about whether they remember the turn for the better, and that’s best explained by hedonism.

Additionally, according to the B theory of time, there is no objective present. Each point in time is a point on a four dimensional spacetime block--there is no objective now. This would mean that while some points causally precede others, there is no objectively real before than relationship. The phil papers survey shows that the B theory of time is the consensus view among philosophers about time. Thus, it’s not clear that the before than relationship is ontologically real.

Even if it is, it only seems to matter if it affects experience. Imagine a scenario in which the world in the year 4000 is exactly the same as the world in the year 5000. Consider a scenario in which a person is created in the year 4000, as a full 60 year old adult. They have memories of a previous life from before they were 60, but those memories were falsely implanted given that they did not exist prior to being created at 60. Prior to being created at 60, a philosophical zombie filled in for them.

Additionally, the person is created in the year 4000 as an infant and experiences the first 60 years of life, before disappearing and being replaced by a philosophical zombie. It seems intuitively that it’s more important for the 60 year old to have a good life. However, the 60 year old was created later in time, and is technically younger. This scenario is analogous to the 60 year old not having the first 60 years of its life, before going into cryogenic sleep, and then awakening having had its aging reversed at the age of 1.

Such scenarios show that the precise temporal point at which experiences happen doesn’t matter. Rather, the significant thing is how those experiences relate to other experiences. Yet that is a hedonistic consideration.

Premise 3 seems to follow straightforwardly from impartiality. From a fully impartial view, there is no reason to privilege the good of anyone over the good of any other.

(Chappell, 2011) argues for value holism, according to which the value of lives should be judged as a whole, rather than merely by adding up the value of each moment. He first argues that directional trends matter--a claim addressed above.

Next (p.7) he cites Kahneman’s research, finding people often will prefer additional pain as long as the end of some experience is good. People judge 60 seconds of very painful cold water followed by 30 seconds of less painful cold water to be less unpleasant than merely 60 seconds of very painful cold water. However, the fact that people do judge particular moments to be more unpleasant than other ones does not mean that those moments are in fact more unpleasant than the other ones. Additionally, if asked during the experience, people would clearly prefer to not have to undergo the extra 30 seconds.

Chappell responds to this (p.8), writing,

“Yet when making an overall judgment from ‘above the fray’, so to speak, the subjects express a conflicting preference, and merely noting the conflict does not tell us how to resolve it. As a general rule, we tend to privilege (reflective) global preferences over (momentary) local ones: such a hierarchy is, after all, essential for the exercise of self-control.”

This is true in general. However, some judgments can be unreliable. The judgment that extra pain makes an experience better seems very plausibly a result of biases, as people privilege the end of an experience over the beginning. The Kahneman research seems more like a debunking of the judgments Chappell appeals to.

Next, Chappell says (p.9)

“But for this to qualify as independent evidence of factual error, we must assume that subjects were interpreting ‘overall discomfort’ to mean ‘aggregate momentary discomfort’. This seems unlikely. It’s far more plausible to think that subjects were simply reiterating their holistic judgment that the longer trial was less unpleasant on the whole. So these considerations leave us at a dialectical impasse.”

Additionally, people are often unaware of their motivations and introspection is often unreliable (Schwitzgebel, 2008). We thus shouldn’t be overly deferential to people’s judgments of their own experience.

The principles Chappell appeals to are far less intuitive than the notion that previous events that are no longer causally efficacious cannot causally impact the goodness of a particular action. For example, if I spawned last Thursday with full memories, it would seem unintuitive that that undermines the value of future experiences, even if they serve the same functional role.

In the case given by Kahneman, imagine that one was brought into existence after the minute of pain, with full memories as if they’d experienced the minute of pain, despite never having done so. In that case, it seems like it would be better for them to endure no suffering, rather than to endure the extra 30 seconds of suffering. To accomodate this intuition, combined with value holism, one would have to say that one of the experiences somehow changes the badness of the other one, in a way not achieved if it were replaced by a memory that’s functionally isomorphic--at least when it comes to their evaluation of the other experience.

(McNaughton & Rawling, 2009) additionally argue against this view, while still maintaining a version of value holism, arguing that the value of a collection of experiences can produce more momentary experience than the value of each part of it. They give (p.361) the following analogy.

“An analogy might help in drawing the distinction between our position and Moore’s. One might think of a state of affairs as in a some ways like a work of art—say, Michelangelo’s David. (Moore discusses the value of a human arm,16 and our discussion here will draw on this to some extent.) On both our account and Moore’s, the value of David is significant. For Moore, however, it might well be that its entire value is its value as a whole. On this account of matters, any part taken in isolation (David’s nose, say) has zero value. We agree that any part taken in isolation has zero value—but we contend that this way of valuing the parts is simply irrelevant to the evaluation of the statue. Rather, the relevant value of David’s nose is the value of its contribution to the statue. Perhaps David’s hand contributes more than his nose, in which case the value of the former is more than the value of the latter.”

An additional worry with value holism is that it requires strong emergence--positing that the whole value of an experience is not reducible to its parts. Rather, its parts take on a fully different property when combined--a property that is not merely the collection of a variety of parts operating at lower levels. As (Chalmers, 2006) argues, we have no clear examples of strong emergence. The only potentially strongly emergent phenomena is consciousness, which means we have good reason to doubt any theory that posits strong emergence. If value holism requires positing a property that exists nowhere else in the universe--that makes it extraordinarily implausible.

(Alm, 2006) presents an additional objection to value holism--defending atomism, writing (p.312)

“Atomism is defined as the view that the moral value of any object is ultimately determined by simple features whose contribution to the value of an object is always the same, independently of context.” Over the course of the article, (p.312) “Three theses are defended, which together entail atomism: (1) All objects have their moral value ultimately in virtue of morally fundamental features; (2) If a feature is morally fundamental, then its contribution is always the same; (3) Morally fundamental features are simple.”

The first premise is relatively uncontroversial. There are certain basic features that confer moral significance. Nothing other than those features could, even in principle, confer value on a state of affairs.

The second premise is likewise obvious. For one feature to be significant in one case but not in another case, there would have to be some element of the feature that varies across cases. Yet it could only do so by the feature conferring moral worth only in some cases, which would mean it doesn’t vary across cases. The rule “donate to charity only if it maximizes well-being,” doesn’t vary across cases because the rule is always the same, even though its application varies from case to case.

The third premise defines simple features as ones not composed of simpler parts. Several reasons are given to think the fundamental features will be simple (p. 324-326).

We have general prima facie reason to expect explanations to be simple, for the general reason that simplicity is a theoretical virtue. A more complex account that has to posit more things is intrinsically less likely. In physics, for example, we take there to be a strong reason to reject complex features as fundamental, that operate on the levels of organisms, rather than fundamental physics.

Positing new properties gained when fundamental properties are combined involves immense metaphysical weirdness. It seems hard to imagine that pleasure would have no value, knowledge has no value, but pleasure and knowledge gain extra value when they combine--in virtue of no fact about either of them.

Utilitarianism Wins Outright Part 27

A Few More Cases That Other Theories Struggle To Account For

Introduction

Utilitarianism, unlike other theories, gives relatively clear verdicts about a variety of cases. This makes it easily criticizeable—one can very easily find seemingly unintuitive things it says. Other theories, however, are far vaguer, making it harder to figure out exactly what they say.

There are lots of situations that utilitarianism adequately accounts for that other theories can’t account for. I’ve already documented several of them. I shall document more of them here.

1 Children

Consequentialism provides the only adequate account of how we should treat children. Several actions being done to children are widely regarded as justifiable, yet are not for adults.

Compelling them to do minimal forced labor (chores).

Compelling them to spend hours a day at school, even if they vehemently dissent and would like to not be at school.

Forcing them to learn things like multiplication, even if they don’t want to.

Forcing them to go to bed when their parents think will make things go best, rather than when they want to.

Not allowing them to leave your house, however much they protest.

Disciplining them in ways that cause them to cry, for example putting them on time-out.

Controlling the food they eat, who they spend time with, what they do, and where they are at all times.

However, lots of other actions are justifiable to do with adults, yet not with children.

Having sex with them if they verbally consent.

Not feeding them (i.e. one shouldn’t be arrested if they don’t feed a homeless person nearby. They should, however, if they don’t feed their children. Not feeding ones children is morally worse than beating their children, while the same is not true of unrelated adults.)

Employing them in damaging manual labor.

Consequentialism provides the best account of these obligations. Each of these obligations makes things go best, which is why they apply. Non consequentialist accounts have trouble with these cases.

One might object that children can’t consent to many of these things, which makes up the difference. However, consent fails to provide an explanation. It would be strange to say, for example, that the reason you can prohibit someone from leaving your house is because they don’t consent to leaving your house. Children are frequently forced to do things without consent, like learn multiplication, go to school, and even not put their fingers in electrical sockets. Thus, any satisfactory account has to explain why their inability to consent only bars them from consenting to some of those things.

2 War

Consequentialism also provides the best account of when war is justified. Usually, it’s immoral to kill innocent people. However, in war there is an exception.

(Lazar 2016) provides an account based in just war theory of when war is justified. However, Lazar’s criteria are bizarre, ad hoc, and clearly derivative of more basic principles. Utilitarianism provides a much better account of just war.

On utilitarianism, war is justified if it maximizes desirability of mental states of sentient beings. If it makes sentient beings' lives better overall, then war is justified.

Lazar lays out several necessary criteria of just war.

“1. Just Cause: the war is an attempt to avert the right kind of injury.”

This diverges slightly from utilitarianism in two ways, which make the utilitarian account clearly better. First, the utilitarian account does not take into account intentions. If an actor achieves a desirable end, even if their aim was ignoble, the war would be good overall. For example, if the U.S. decision to intervene in world war two was driven by bad motivations, that would not mean that U.S. intervention decreasing the length of the holocaust and war wouldn’t make the war good overall.

Second, the utilitarian account is proportional. Rather than saying that wars can only be justified to avert the right kind of injury, it would say that wars can only be justified if the benefits of the war outweigh the costs. Thus, even if the injury were very great, if the costs of the war were greater, war would not be justified. This is rather intuitive, if combatting a genocide going on in China would result in nuclear anhiliation of the world, it would not be desirable. Similarly, it says that the bar for justifying a more modest intervention is much lower. This is also intuitive, if the cost to prevent several hundred thousand deaths would be a drone strike that would cost a few hundred lives, intervening would be good. Rather than drawing arbitrary lines for how great the atrocity has to be to justify an intervention, utilitarianism rightly holds that analysis should compare the benefits and costs of expected intervention.

When justifying this principle, Lazar appeals to the immense harms of war. However, analyzing the harms of war to justify treading lightly when it comes to war appeals to consequentialism, because it uses the negative consequences as a justification for being hesitant about going to war.

Next, Lazar says “Legitimate Authority: the war is fought by an entity that has the authority to fight such wars.”

The utilitarian account is once again better here. First, as I argued in part 1 of the chapter, utilitarianism provides the only adequate account of political authority. Second, it seems clear that the authority of the entity going to war is not relevant for evaluating the desirability of a war. If an illegitimate criminal enterprise went to war against the Nazi’s, thereby quickly ending the holocaust, even though the illegitimate criminal enterprise wouldn’t be legitimate, the war would still be desirable. Third, this standard is clearly ad hoc. Utilitarianism provides the best grounding of the arbitrary list of requirements for war to be justified.

Lazar next says “Right Intention: that entity intends to achieve the just cause, rather than using it as an excuse to achieve some wrongful end.”

Intention is irrelevant, as I argued above. It’s also unclear how we ascribe intentions to a government. Different people in the government no doubt have different intentions relating to war. There is no single intention behind the decision to intervene.

Lazar’s fourth criterion is “Reasonable Prospects of Success: the war is sufficiently likely to achieve its aims.”

Once again, consequentialism provides a better account. First, even if a war isn’t likely to achieve its aims, if it ends up producing good outcomes, consequentialism explains why it’s justified. If the decision to intervene intends to bring democracy to a region, fails to do so, but ends up saving the world, that intervention would be good overall. Second, even if a war is unlikely to achieve its aims, if its aims are sufficiently important, the war can still be justified. If a war has a 3% chance of saving the world, it would be justified, despite being unlikely to succeed. Third, a war only gains justification from being likely to achieve its aims if those aims are desirable. Fourth, consequentialism provides an adequate account of why likelihood of success matters. Better consequences are brought about by wars that are likely to produce good outcomes.

Fifth, Lazar says “Proportionality: the morally weighted goods achieved by the war outweigh the morally weighted bads that it will cause.”

This is true, yet perfectly in accordance with the consequentialist account. This criterion is essentially that war is justified only if the expected benefits outweigh the costs, which is identical to the utilitarian account of when war is justified.

Sixth, Lazar says “Last Resort (Necessity): there is no other less harmful way to achieve the just cause.”

This criteria is ambiguous. If the claims is merely that war should only be done if it’s the best option, and if other options are better they should be done instead, that’s clearly true, and it’s accounted for by utilitarianism. However, the mere existence of less harmful ways of achieving the aim of war wouldn’t affect the morality of the war. If intervening would be desirable, but sanctions would be even more desirable, that’s a reason to choose sanctions if one has the option of selecting either sanctions or war. However, if one does not have the option of imposing sanctions, the existence of potentially desirable sanctions wouldn’t affect the desirability of going to war.

Lazar goes on to provide necessary criteria for the conduct practiced in war to be justified, even if the war itself is justified.

“Discrimination: belligerents must always distinguish between military objectives and civilians, and intentionally attack only military objectives.”

This is a good heuristic, but the utilitarian account is better. If intentionally targeting one enemy civilian would end a war and save millions of lives, doing so would be justified.

Additionally, this criteria seems to draw a line between intentionally targeting civilians and targeting them as collateral. Utilitarianism adequately explains why that distinction is morally irrelevant. If given the choice between killing 100 enemy civilians as collateral damage or 10 intentionally, utilitarianism explains why killing the 10 would be preferable.

Second, Lazar says “Proportionality: foreseen but unintended harms must be proportionate to the military advantage achieved.”

Utilitarianism explains why this is false. First, it explains why there’s no morally relevant difference between a foreseen but unintended harm and an intended harm. It would be better to kill 10 people intentionally than 15 people in a way that’s foreseen yet not intended. Second, it explains why harm to civilians that doesn’t achieve a military advantage can still be desirable. If, for example, bombing of 15 civilians prevented 500 extra civilian deaths, even if no military advantage was achieved, the bombing would still be justified. Third, utilitarianism provides an account of why the harms and benefits should be proportional in war.

Third, Lazar says “Necessity: the least harmful means feasible must be used.”

Utilitarianism can account for why the least harm should be caused. However, it also accounts for why it can be good for an action to happen even if it’s not the least harmful. Even if there’s a better option than bombing people, if bombing people makes the world better, utilitarianism explains why it’s still justified.

3 Pollution

Some types of pollution should clearly be prohibited. (Slaper et al, 2013) argues that the Montreal Protocol, for example, prevented millions of cases of skin cancer per year. It did this at a relatively low cost. Most would agree that if a policy produced minimal economic harm and prevented millions of cases of cancer every year, it would be good overall.

However, some types of pollution clearly shouldn’t be polluted. When a person lights a candle, the ash goes into the air, affecting people for miles around. When people exhale they release a bit of CO2, without the consent of anyone else. Consequentialism provides the best account of when pollution is justified.

Any time someone pollutes, they affect people who do not consent. Pollutants are breathed in by those who do not consent. However, it only makes sense to ban pollutants that are actually harmful. Consequentialism best accounts for this fact.

It seems clear that a pollutant should be banned only if it’s harmful. (Lewis, 2015) argues that PFAS pollutants are quite common, affecting vast numbers of people. Whether or not it makes sense to ban or regulate PFAS seems to hinge on whether or not they are harmful. If it turned out that PFAS was not harmful, there would be no rationale for banning it. Other theories have difficulty accounting for why pollutants being harmful are the necessary and sufficient conditions for a pollutant being ban-worthy. Indeed, the importance of banning a pollutant scales proportionally to how much harm the pollutant does.

4 Political Authority

(Huemer, 2013) has argued persuasively that government action looks suspiciously like theft. After all, governments take our money without consent. That tends to be how most people define theft. However, despite this, the notion that taxation is good if it produces greater overall benefits is quite intuitive. Thus, utilitarianism gives the best account of why political authority is not necessarily objectionable. If the government takes money to spend it to save the life of someone else, that is overall good.

Huemer considers a case wherein a person often kidnaps people and puts them in their basement whenever they commit a crime, while demanding payments from people. This would clearly be unjust. However, a government is structurally similar, demanding payment without consent and imprisoning people. What would be the morally relevant difference between those two cases? The utilitarian can supply an adequate account: bands of roving vigilantes does not bring about good outcomes, while a state (plausibly) does. Theft causes harm in a way that taxation does not.

One might object that the legitimacy of political authority comes from implicit consent. However, Huemer explains why this does not work. For consent to be valid, people have to be able to opt out reasonably, explicit dissent has to trump implicit consent, consent has to be voluntary, and obligations have to be both mutual and conditional. Political authority lacks any of these features. One cannot easily opt out of government. Huemer quotes Hume, who said “We may as well assert that a man, by remaining in a vessel, freely consents to the dominion of the master; though he was carried on board while asleep, and must leap into the ocean, and perish, the moment he leaves her.”

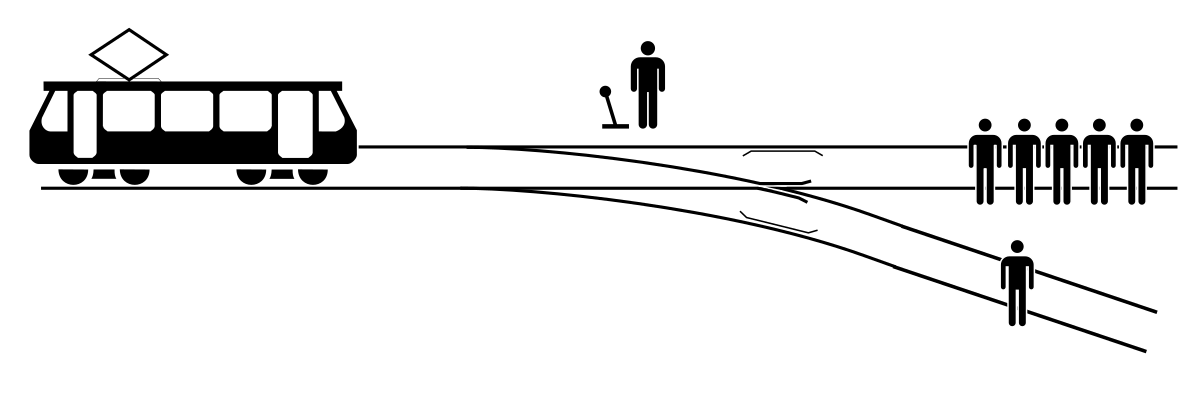

Pushing The Guy Off The Bridge And Flipping The Switch Aren't Morally Different By More Than An Arbitrarily Small Finite Amount Of Utility

Assuming modest assumptions

People often hold two judgments which appear to be in tension with each other. In the case of the trolley problem, where there is a train going towards 5 people unless you flip the switch to kill one person, people think you should flip the switch. However, in a different case, where the only way to stop a train from killing 5 people is to push one person off a bridge, people tend to think1 you shouldn’t push the guy. As I shall argue here, the moral equivalent is not merely superficial—those two actions are not morally different from each other. One’s judgment should thus be consistent across the cases.

This follows from an even more modest pareto principle, which says that if some action makes all affected parties better off, it is a good action. This is a rather plausible principle.

Next, consider the following case. One person is on a track over a bridge. A train is coming. There is a different track that leads up to the person over the bridge. There are two ways of stopping the train.

Flip the switch to redirect the train to to one person above.

Push the person onto the track. Doing so would have the additional effect of very very slightly increasing the utility of both the person pushed and of all of the other people on the tracks, relative to redirecting the train2.

It seems obvious that the better option is option 2. Option 2 is better than option 1 for all of the affected parties. However, option 2 is only an infinitesimal amount better than the ordinary case in which one pushes the person off the bridge. Thus, 2 which is an infinitesimal amount better pushing the guy is better than flipping the switch.

My Issue With The Way Lots Of Utilitarians Argue For Utilitarianism

Against Huemerless utilitarianism

Philosophy rarely proceeds by way of knock down, deductive argument. Instead, a better way to proceed is to compare theories holistically and abductively, as explanations of phenomena. Thus, as a cautionary note to other utilitarians, I’d recommend that, rather than attempt to provide a single knockdown deductive argument, they proceed abductively and compare a wide range of verdicts. This is probably the biggest evolution in my thinking over the years.

Given that the deductive arguments are only as intuitive as the conjunction of all of the premises, even the deductive arguments proceed by analysis of the intuitive plausibility of certain notions. And yet if there’s a pretty intuitive premise, but it entails dozens of hideously unintuitive things, that premise should likely be rejected.

To illustrate with an example, the simplest application of the argument of (Harsanyi, 1975) would entail average utilitarianism, though it can certainly be employed to argue for total utilitarianism, if we include future possible people in our analysis. However, the reason I reject Harsanyi’s argument as showing average utilitarianism is not because I think the argument trivially provides greater support for average utilitarianism than for total utilitarianism. Instead, it’s because average utilitarianism produces wildly implausible results. Consider the following cases.

We have 1 billion people with -100^100^100^100^100^100^100^100 utility. You have the choice of bringing an extra 100^100^100^100^1000 people into existence with average utility of -100^100^100^100^100^100^100^99. Should you do it? It would increase average utility, yet it still seems clearly wrong—as clearly wrong as anything. Bringing miserable people into existence who experience more than the total suffering of the holocaust every second is not a good thing, even if there are existing slightly less miserable people.

There is currently one person in existence with utility of 100^100^100. You can bring a new person into existence with utility of 100^100^10. Average utilitarianism would imply that, not only should you not do this, doing it would be the single worst act in history, orders of magnitude worse than the holocaust in our world.

You are in the garden of Eden. There are 3 people, Adam (utility 5), Eve (utility 5), and God (utility 10000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000^1000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000^100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000). Average utilitarianism would say that Adam and Eve existing was a tragedy and they should certainly avoid having children.

You’re planning on having a kid with utility of 100^100, waaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaay higher than that of most humans. However, you discover that there are oodles of aliens with utility much higher than that. Average utilitarianism would say you shouldn’t have the child, because of the existence of the far away aliens who you’ll never interact with.

Average utilitarianism would say that if fetuses had a millisecond of joy at the moment of conception, this would radically decrease the value of the world, because fetuses would bring down average utility.

Similarly, if you became convinced that there were lots of aliens with bad lives, AU would say you should have as many kids as possible, even if they had bad lives, to bring up the average.

These cases are why I reject average utilitarianism. If total utilitarianism had implications that were as unintuitive as those of average utilitarianism, I would similarly reject it, despite the deductive arguments. The deductive arguments count strongly in favor of the theory, but would not be enough to overcome the hurdles of the theory, if it were truly unintuitive across the board.

Utilitarians will often try to discredit intuitions as a way of gaining knowledge, (E.G. Sinhababu 2012). They will often point out the poor track record of intuitions. However, this does mean that intuitions are less reliable than they would otherwise be, but it does not mean we should simply ignore intuitions. Absent relying on what seems to be the case after careful reflection, we could know nothing, as (Huemer, 2007) has argued persuasively. Several cases show that intuitions are indispensable towards having any knowledge and doing any productive moral reasoning.

Any argument against intuitions is one that we’d only accept if it seems true after reflection, which once again relies on seemings. Thus, rejection of intuitions is self defeating, because we wouldn’t accept it if its premises didn’t seem true.

Any time we consider any view which has some arguments both for and against it, wecan only rely on our seemings to conclude which argument is stronger. For example, when deciding whether or not god exists, most would be willing to grant that there is some evidence on both sides. The probability of existence on theism is higher than on atheism, for example, because theism entails that something exists, while the probability of god being hidden is higher on atheism, because the probability of god revealing himself on atheism is zero. Thus, there are arguments on both sides, so any time we evaluate whether theism is true, we must compare the strength of the evidence on both sides. This will require reliance on seemings. The same broad principle is true for any issue we evaluate, be it religious, philosophical, or political.

Consider a series of things we take to be true which we can’t verify. Examples include the laws of logic would hold in a parallel universe, things can’t have a color without a shape, the laws of physics could have been different, implicit in any moral claim about x being bad there is a counterfactual claim that had x not occurred things would be better, and assuming space is not curved the shortest different between any two points is a straight line. We can’t verify those claims directly, but we’re justified in believing them because they seem true--we can intuitively grasp that they are justified.