My friend Aaron Bergman has recently written an article, playing devil’s advocate1 to the claim that we should try very hard to prevent the end of the world. In it, Bergman makes the case for some form of suffering focused ethics—a view I’ve previously argued against2. This article shall criticize Bergman’s view. Bergman intends to argue for the following thesis3.

Under a form of utilitarianism that places happiness and suffering on the same moral axis and allows that the former can be traded off against the latter, one might nevertheless conclude that some instantiations2 of suffering cannot be offset or justified by even an arbitrarily large amount of wellbeing.

Nearly every view can be coherently held. The more important question is whether a view can be held without having deranged or implausible implications. This more daunting requirement is one which Bergman’s view is unable to meet, as we shall see. Bergman writes

For myself and I believe many others, though, I think these “preferences” are in another sense a stronger claim about the hypothetical preferences of some idealized, maximally rational self-interested agent. This hypothetical being’s sole goal is to maximize the moral value corresponding to his own valence. He has perfect knowledge of his own experience and suffers from no cognitive biases. You can’t give him a drug to make him “want” to be tortured, and he must contend with no pesky vestigial evolutionary instincts.

Those us who endorse this stronger claim will find that, by construction, this agent’s preferences are identical to at least one of the following (depending on your metaethics):

One’s own preferences or idealized preferences

What is morally good, all else equal

For instance, if I declare that “I’d like to jump into the cold lake in order to swim with my friends,” I am claiming that this hypothetical agent would make the same choice. And when I say that there is no amount of happiness you could offer me in exchange for a week of torture, I am likewise claiming this agent would agree with me.

Consider a particular instance of egregious torture—one which Bergman wouldn’t trade for the world. Surely one instance of this torture is less bad than two instances of slightly less gruesome torture, each of which are less bad than two instances of torture slightly less gruesome… until we get, by transitivity, the conclusion that a very horrific form of torture is less bad than a vast number of instances of mild pain. However, a vast number of instances of mild pain can clearly be traded off against enormous pleasures. By the above reasoning, one torture is less bad than a ton of pinpricks, but pinpricks can be weighed against positive pleasures. Thus, by transitivity, so can torture.

I’ve discussed the matter with Aaron briefly and his response was primarily to say that on a utility scale, horrific torture is infinitely awful. This is, however, false. When Aaron says that it’s infinite on the negative utility scale, this is, in one sense, repeating the original claim, namely, that horrific torture can’t be outweighed by finite goods. However, when I described scaling down the misery, I wasn’t describing utility in the VNM sense of how aversive a rational being would find an experience. Instead, I was describing it in the far more trivial sense of just how much pain was caused. While the precise numbers we assign are arbitrary, there are clearly more painful experiences, and there are also clearly less painful experiences. When we describe the suffering diminishing, we can just think of making the experience slightly less awful. For any awful torture, there are a possible number of diminishments that would make it not awful. Surely this is a concept that we can all conceive of quite readily. However, if one makes an experience less awful enough times, it will eventually not be awful at all.

So, while I talked a lot about utility assignments in my conversation with Aaron, we don’t even need to attach a utility scale. All we have to accept is that very awful things can be made slightly less awful, until they’re barely awful at all. This is a very plausible claim; almost impossible to deny. If we accept that making it less awful but affect more people brings about something overall worse and transitivity, then we arrive inescapably at the conclusion that suffering of the most extreme variety can eventually be outweighed by garden variety pleasures.

This conclusion is exactly what we expect on first blush. The earth weighs a lot, but its weight can be surpassed by enough feathers. I am very tall (a whole whopping 5’7!), but my height can be outweighed by enough combined ant heights. Generally, things that are immense in a particular respect can be surpassed in that respect by a vast number of things that are meager in the same respect.

One other slightly troubling implication of Aaron’s view that they admitted freely was that it plausibly entailed—if we assume one is more likely to be kidnapped and thus heinously tortured if they go outside, an assumption Aaron was uncertain about—Aaron’s view entails that a perfectly rational agent would never go outside for trivial reasons. For example, if one was perfectly rational, they would never go to the pub with friends, given that there is a non-zero risk of being kidnapped and horrifically tortured. Even one who has initial suffering focused intuitions will plausibly be put off by this rather troubling implication of the view. In fact, Aaron goes so far as to agree that this would hold even if the difference in kidnap and torture rates were one in 100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000^100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000^10000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000, meaning the universe would almost certainly end before there is a difference in torture rates of even one person. This is an enormous bullet to bite.

In defending this fairly radical implication, Aaron says

But this all seems beside the point, because we humans are biological creatures forged by evolution who are demonstrably poor at reasoning about astronomically good or bad outcomes and very small probabilities. Even if we stipulate that, say, walking to the grocery store increases ones’ risk of being tortured and there exists a viable alternative, the fact that a person chooses to make this excursion seems like only very weak evidence that such a choice is rational.

It’s true that all of our views are somewhat influenced by evolution, and thus susceptible to distorting factors. Yet it seems the plethora of biases relating to our inability to conceive of large numbers end up making the plethora of biases favor my view. Additionally, despite evolutionary forces undermining the reliability of our intuitions, people are still (reasonably) good judges of what makes them well off. A view that entails that walking outside is foolish most of the time will need some other way to offset its wild unintuitiveness. Most people are right about basic prudential matters most of the time. Pious moral proclamations are generally worse judges of the things that make people well off than what people do in their everyday lives. But even if we think how people in fact act is largely irrelevant, the hypotheticals I’ve given with greatly diminished risk should still hold force.

Aaron formalizes his argument as follows.

(Premise) One of the following three things is true:

One would not accept a week of the worst torture conceptually possible in exchange for an arbitrarily large amount of happiness for an arbitrarily long time.6

One would not accept such a trade, but believes that a perfectly rational, self-interested hedonist would accept it; further this belief is predicated on the existence of compelling arguments in favor of the following:

Proposition (i): any finite amount of harm can be “offset” or morally justified by some arbitrarily large amount of wellbeing.

One would accept such a trade, and further this belief is predicated on the existence of compelling arguments in favor of proposition (i).

(Premise) In the absence of compelling arguments for proposition (i), one should defer to one’s intuition that some large amounts of harm cannot be morally justified.

(Premise) There exist no compelling arguments for proposition (i).

(Conclusion) Therefore, one should believe that some large amounts of harm cannot be ethically outweighed by any amount of happiness.

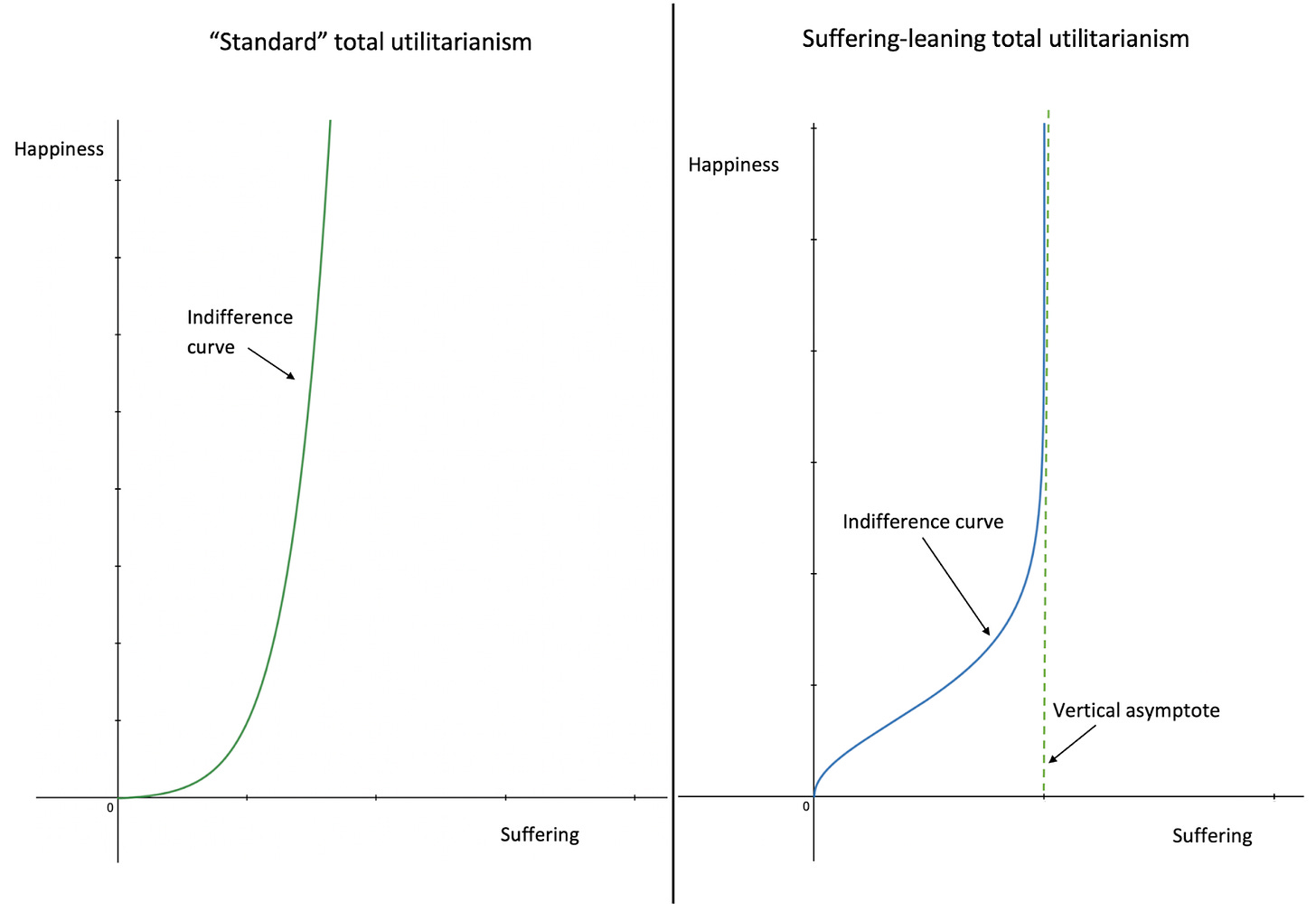

I reject one and would accept the trade, largely for the reasons described above. I similarly reject 3, having, in my view, just dispensed several. Aaron describes the following indifference curve, the second one matching his own.

While you can have an indifference curve like this, it is prone to some bizarre conclusions. The point at the vertical asymptote does not seem infinitely more horrible than the point a tiny bit away from the vertical asymptote. These are really, very small differences. Asymptotically approaching a particular point does give the appearance of greater reasonability, but this appearance is only apparent. As long as we accept that making the pain lessen by some very small amount, say 1/100,000,000th the badness of torture, at no point4 makes the situation less than half as bad, then we get the conclusion that things are not incommensurable5. Bergman’s indifference curve would have to deny this very reasonable assumption. It only has the appearance of reasonability because exponential growth curves are hard to follow and look like they asymptotically approach a point, even when they, in fact, do not. Bergman would have to accept that a certainty of suffering at the highest point on the graph as presented—very near the asymptote—would be less bad than a one in a billion chance of having a one in a billion chance of having a one in a billion chance… and so on for a billion more iterations of this, of having the suffering that’s right at the asymptote. Aaron continues

To rephrase that more technically, the moral value of hedonic states may not be well-modeled by the finite real numbers, which many utilitarians seem to implicitly take as inherently or obviously true. In other words, that is, we have no affirmative reason to believe that every conceivable amount of suffering or pleasure is ethically congruent to some real finite number, such as -2 for a papercut or -2B for a week of torture.

While two states of the world must be ordinally comparable, and thus representable by a utility function, to the best of my knowledge there is no logical or mathematical argument that “units” of utility exist in some meaningful way and thus imply that the ordinal utility function representing total hedonic utilitarianism is just a mathematical rephrasing of cardinal, finite “amounts” of utility.

Well, the vnm formula shows one’s preferences will be modellable as a utility function if they meet a few basic axioms. Let’s say a papercut is -n and torture is -2 billion. To find n, we just need to find a number for which we’d be indifferent between a certainty of a papercut and n/2 billion risk of torture. Bergman is aware of this fact. I think his point here is that there’s no in principle reason why certain things can’t be incommensurable—having, for example, torture be infinitely worse than a papercut. I agree with Aaron here—I think, for example, infinite suffering should be modeled as negative infinity. So Aaron and I agree that one can have a perfectly coherent set of assumptions under which we don’t just assign non-infinite numbers to every experience. Our disagreement is about whether non-infinite amounts of suffering should be assigned negative infinite utility.

Aaron’s case for the view that negative experiences should dominate our considerations is largely based on intuitions about how horrible negative experiences are. Several things are worth noting

First, as Huemer argues in his paper in defence of repugnance6, we’re very bad at reasoning about big numbers; the types of intuitions that Aaron appeals to are precisely the ones we should be debunking.

Second, we have the ability to grasp, to some degree, just how horrible the worst conceivable experiences are. We can, for example, gain some intuitive appreciation of how horrific it would be to be devoured by a school of piranhas or to burn to death. We cannot, however, adequately appreciate the unimaginably good experiences that could exist in our posthuman future. It seems quite possible, indeed likely even, that once we can modify our consciousness, we’d be able to have experiences that are as desirable as being tortured is undesirable. The subjective experience of something that feels as good as being burned to death feels bad, being experienced for a thousand years makes every experience had so far by humans appear as a meagre scintilla of what could be to come, so far outclassed by what could be possible in the future. We in fact have good reason to think that pleasure and suffering are logarithmic7. Thus, it’s quite plausible that extreme experiences should dominate our ethical calculus, on both the positive and the negative end, even if the intuitions to which Aaron appeals should be believed. This provides a more parsimonious explanation of the overwhelming badness of suffering, while avoiding a puzzling asymmetry.

Third, when one really considers their intuitions about the badness of vicious torture those who conclude that it is infinitely worse than pinpricks seem to me to be going very far astray. Considering how bad torture is can, in my view, give one the belief that torture is very, very bad, but I’m unsure how, even in principle, it can give the belief that it’s infinitely bad. This intuition seems much like the intuition that monkeys will never type out Shakespeare. It will, no doubt, take them a supremely long time to do so, just as it would take an obscenely large number of dust specks to outweigh a torture, but it seems a mistake to believe that there’s some firm, uncrossable barrier, in either case. Bergman’s belief in this barrier based merely on a series of flimsy intuitions, which clash with several converging much stronger intuitions, seems to be a grave mistake.

Bergman, My case for “suffering-leaning ethics,” 2022

Omnizoid (this is me, for the record), Against Negative Utilitarianism, 2021

Bergman, My case for “suffering-leaning ethics,” 2022

Other than, of course, moving from slight suffering to no suffering

Of course, this still gets us with a very extreme weighting of things. This can be show rather easily. If things at no point get half as horrible then the upper bound for how much worse vicious torture is than the experience that had 99,999,999/100,000,000 of the badness of vicious torture removed is 2^99,999,999

Huemer, In Defence Of Repugnance, 2008

> I reject one and would accept the trade, largely for the reasons described above.

The way the trade is presented this is clearly false. You have a good imagination. I have a good imagination. The worst torture that could be thought up by a perfectly imaginative being would undoubtably get to negative infinity utility.

Secondly,

> Surely one instance of this torture is less bad than two instances of slightly less gruesome torture…

This is a strong argument, but I don’t think it’s necessarily true. It seems plausible that some forms of torture could act like a clean breaking piecewise function instead of a curve.

Imagine for a moment you tried answering a code of ethics that said murder was the ultimate wrong with this argument. You can’t imagine being slightly “less dead” such that you could eventually only be “a little dead” at which other considerations outweigh. Dead is Dead! (Insert meme here).

So yeah I don’t think it necessarily applies.

*However*

Isn’t there an even simpler response to this kind of negative util? The preference charts given here have a vertical asymptote at some value p of suffering.

What about value of suffering 2p? It seems like 2p is either out of the domain of the function, which is absurd, equal to p, which is also absurd, or scales linearly with an increased coefficient. I don’t think the latter makes either conceptual sense with the idea of a “critical value” of negative utility, or mathematical sense with regards to operations involving infinities.

Nice response, thanks for engaging with it. I'll write a more complete response soon, but my basic thoughts are that:

1) I bite most of the bullets you list, except:

2) VNM shows that preferences have to be modeled by an *ordinal* utility function. You write that

"Well, the vnm formula shows one’s preferences will be modellable as a utility function if they meet a few basic axioms. Let’s say a papercut is -n and torture is -2 billion."

but this only shows that the torture is worse than the papercut - not that it is any particular amount worse.

Afaik there's no argument or proof that one state of the world represented by (ordinal) utility u_1 is necessarily some finite number of times better or worse than some other state of the world represented by u_2