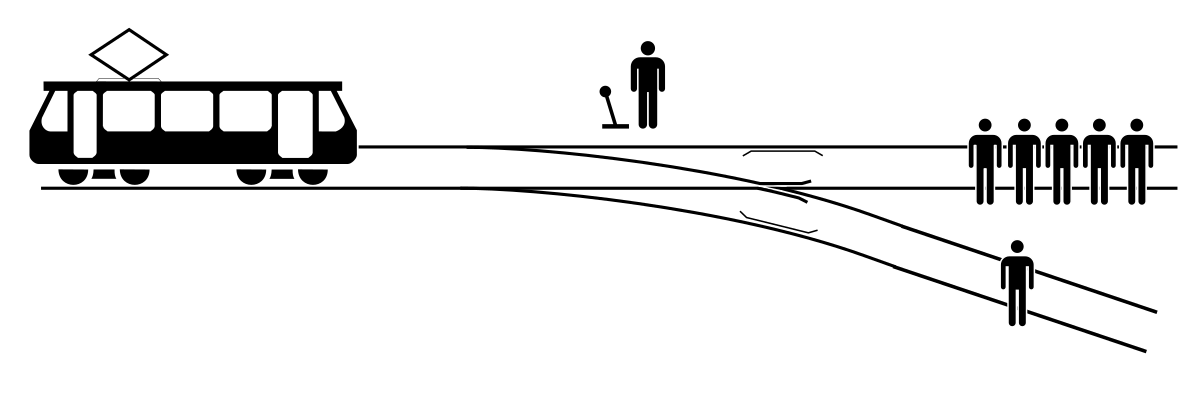

The trolley problem involves a train going down a track that will hit five people. However, if you flip the switch, it will redirect one. Should you flip the switch? No! I shall present lots of reasons in this article.

Objection 1: The No Good Account Objection

According to this objection, there is no adequate account of why flipping the switch is objectionable that wouldn’t apply to many other cases.

I will defend the view that one ought to flip the switch in the trolley problem. The utilitarian defense of this is somewhat straightforward, flipping the switch saves the most lives, and thus makes the world maximally better. However, there are a series of principles to which one could appeal to argue against flipping the switch. In this section, I will argue against them

The first view shall be referred to as view A.

According to view A, it is impermissible to flip the switch, because a person ought not take actions that directly harm another without their consent.

However, this view seems wrong for several reasons

First, an entailment of this view is that one oughtn’t steal a dime, in order to save the world, which seems intuitively implausible

Second, this view is insufficient to demonstrate that one oughtn’t flip the switch unless one has a view of causality that excludes negative causality, ie a view which claims that harm caused by inaction is not a direct harm caused by action. Given that not flipping the switch is itself an action, one needs a view of direct causation that excludes failing to take an action. However, such a view is suspect for two reasons.

First, it’s not clear that there is such a view that is coherent. One could naively claim that a person could not be held accountable for inaction, yet all actions can be expressed in terms of not taking actions. Murder could be expressed as merely not taking any action in the set of all actions that do not include murder, in which case one could argue that murder is permissible, given that punishing murder is merely punishing a persons failing to take actions in the aforementioned non murder set.

One could take a view called view A1 which states that

A person's action is the direct cause of a harm if them becoming unconscious during that action would negate that harm.

This view would allow a person to argue that one is the direct cause of harm during the trolley problem only if they flip the switch. However this view has quite implausible implications.

It would argue that if a person is driving and sees a child in front of them in the road, and fails to stop their car and runs over the child they would not be at fault, because failing to stop is merely inaction, not action. It would also imply that if a heavy shed was about to fall on five people, yet could be prevented by the press of a button, a person who failed to press the button would not be at fault. Thirdly, it would imply that people are almost never the cause of car related mishaps, because things would surely have gone worse if a person were unconscious while driving. Fourthly, it would entail that a person would not be at fault for failing to intervene during a trust fall exercise over metal spikes. Finally, it would entail that if a person was murdering another by using a machine to drive a metal spike slowly into them, that drove the spike forward up until the press of a button, they only be at fault for initially pressing the button, yet they would not be acting wrongly by allowing the machine to continue it’s ghastly act.

This view is also illogical. Inaction is merely not taking an action. It seems implausible that the moral value of an action would be determined by the harms avoided by being rendered unconscious.

Another view could claim that a person causes an event, if, had that person not existed that event wouldn’t have occurred. However, this is still subject to the aforementioned second objection. It is subject to several other objections

First it would argue that an actress would be at fault if a person became enraged at the shallowness of their life, after seeing an actress act in a movie, and in rage, committed a murder. It would also argue that, assuming Hitlers mothers classmates were almost all responsible for the holocaust, if they changed her life enough to make her baby sufficiently different to have prevented the holocaust. Finally, it would argue that Jeffrey Dahmer would act wrongly to donate to charity, because his non existence would avoid harm.

To resolve these issues one could add in the notion of predictability. They could argue that a person is at fault if their non-existence could be predictably expected to prevent harm. This would still imply that if a heavy shed was about to fall on five people, yet could be prevented by the press of a button, a person who failed to press the button would not be at fault. Furthermore it’s subject to two unintuitive modified trolley problems.

First it implies that if a train were headed towards five people, and one could flip a switch such that it would run over zero people they would not be at fault for not flipping the switch.

Second it has a fairly non intuitive second modified trolley problem. Suppose one is presented with the initial trolley problem, yet trips and accidentally flips the switch. Should they flip the switch back to its initial state, such that five people die, rather than the one. This view would imply that they should. However, this view seems unintuitive, it seems not to matter whether the trolley's position was caused initially by a person's existence.

If one accepts the view that they should flip the switch back to its original position, they’d have to accept that in most situations, if a person's non existence would likely result in the same type of harm, they are not at fault. For example, if it were the case that most doctors would harvest the organs of one to save five, then a person would not be blameworthy for doing it, because if they didn’t exist, another doctor would harvest their organs. It would also say that if the majority of people would flip the switch, and that if a person weren’t on the railroad, another would be, then one ought to flip the switch.

It would also argue that in a world where as a child, I accidentally brought about the demise of Jeffrey Dahmer, it would be permissible to kill all the people who Dahmer would have otherwise killed, assuming I could have knowledge that he would have gone on to murder many people and of who he was going to murder.

Thus it could be revised to be the following

A2 A person's action is responsible for a harm if there would be a less great differential in harm to at least one person between the actual world and a world in which they don’t exist, after taking the action

For example on this view Jim murdering a child would be immoral, because after murdering a child, there is harm to at least one person ie the child which would be prevented by Jim’s non existence, such that had Jim stopped existing the instant before he took the action, there would have been a person who would not have suffered

Yet this view also seems implausible.

Firstly because it sacrifices a good deal of simplicity and elegance. The complexity and ad hoc nature of the principle gives us reason to distrust it relative to a simpler principle.

Secondly, it would entail that if person A came across person B murdering person C by using a machine to drive a metal spike slowly into them, that drove the spike forward up until the press of a button, person A would not be at fault for failing to press the button

Thirdly, it would still entail the permissibility of person C failing to press the button, given that their non existence the moment before would result in the same outcome.

Fourth it would say that if a person saves someone’s life while simultaneously stabbing them, they haven’t violated any ones rights, because their non-existence the moment before would make the person stabbed worse off.

Therefore we have decisive reasons to reject this view

On the other hand, utilitarianism provides a desirable answer to the trolley problem. One should flip the switch because it would maximize happiness. This is thus evidence for utilitarianism.

Objection 2: The Hope Objection

This objection is largely a repackaging of an objection given earlier in this series. It seems plausible that a perfectly benevolent third party observer should hope for the switch to flip naturally, of its own accord. If a benevolent third party observer should hope for X to happen, it seems plausible that it would be moral to do X. After all, they would only hope for it if it’s worth doing.

Objection 3: The Better World Objection

This one is closely related to the hope objection. If the switch flipped naturally of its own accord, the world would be better, with 1 person dying rather than 5. Thus, if we accept that

Giving a perfectly moral person control over whether or not something happens can’t make the world worse.

If a perfectly moral person wouldn’t decide to flip the switch, giving them control over whether or not something (IE the flipping of the switch) happens makes the world worse.

Then we’d have to accept

A perfectly moral person would flip the switch.

Then, if we accept

A perfectly moral person would only take good actions

We’d have to accept

Flipping the switch is a good action.

The advocate of not flipping the switch might object to A. However, this is a significant price to pay, as A is very plausible. The notion that giving more options to those who will always choose correctly won’t make things worse is very plausible. Indeed, it’s supported through the following argument.

All of the objections in part 1 provided against rights could also apply here, so there are lots of other objections--it would, however, be tedious and redundant to repeat all of them.

Objection 4: The Blindfolding Objection

Suppose all of the people in the trolley problem were blindfolded, and thus did not know which side they were on. In this scenario, they would all rationally hope for flipping the switch. It would mean they’d have a 83.33333% chance of survival, rather than a 16.6666666666% chance. However, this case seems to be morally equivalent to the trolley problem case.

If we accept

Morality describes what we’d do if we were fully rational and impartial.

This is plausible, it seems that all accusations of moral failing relate to people either arbitrarily prioritizing certain people or being incorrect about the things that matter. How could one be making a moral failing if they care about the right set of entities and the right things for that set of entities.

Making the people in the trolley problem rational and blindfolded makes them impartial and rational

We can stipulate that the people are rational in this case. Then we’d have to accept

Thus, the moral action would be that which would be consented to by the rational blindfolded people in the trolley problem.

Additionally, the following seems very plausible

The rational blindfolded people in the trolley problem would consent to flipping the switch.

We’d have to accept

Flipping the switch in the trolley problem is the moral action.

This seems plausible. A similar thing can be done for the bridge case involving pushing people off of a bridge to save 5 other people. Our judgment about the wrongness of flipping the switch evaporates when we consider it form the perspective of rational affected parties.

Objection 5: The Flip Objection

Suppose we modify the trolley problem slightly. The trolley will currently hit people A, B, C, D, and E. However, you can flip a switch which will cause the trolley to flip onto a different track, hitting no one, but a different trolley will come out of nowhere and hit people A and B. This seems obviously good, it would save three people and be worse for no one. However, now you’ve created a new trolley which is being launched at two people. It seems like this new trolley which is being launched at two people would be better if it was only launched at a different person, person F. Thus, if we accept that you should make the trolley be replaced by the other trolley, and you should have the other trolley go towards a different person, then the overall state of affairs caused by actions, each of which should be taken, is identical to the trolley problem.

Objection 6: Status Quo Bias Objection

As (Chappell and Meisner, 2022) argues opposition to utilitarian tradeoffs is, in many cases, rooted in status quo bias. After all, if the switch was already flipped, no one would support flipping it back. Thus, it’s only because people want to maintain the status quo that they oppose flipping the switch. If the status quo were different, they wouldn’t support making changes. Thus, there’s a plausible debunking account of anti trolley flipping intuitions.

Objection 7: Billion Objection

Suppose we start with a trolley that will kill 5 billion people. It can be redirected to kill only a billion people. It seems intuitive that it should be directed. Thus, our opposition to such things stem from higher order heuristics. When the stakes are sufficiently large, the intuition begins to flip.

Perhaps one doesn’t share the intuition. Well, if they don’t, this might be a fundamental divergence of intuitions. However, it seems hard to imagine that we’d really prefer the deaths of most people to the deaths of only less than one seventh of people.