Effective altruism, for those who have been living either under a rock in the Bay Area or somewhere outside of the Bay Area, is a philosophy and social movement about doing good effectively. These effective altruists are big on giving to effective charities that distribute malaria bednets, preventing kids from dying, and giving to organizations that help rescue animals from torturous factory farms. They also tend to be supportive of high impact careers.

Lyman Stone has an article out, ostensibly a reply to me, succinctly titled Why Effective Altruism Is Bad. The problem with it is the same as the problem with basically all criticisms of effective altruism—all of its criticisms are bizarre, false, and indicative of very deep confusion. Now, Scott has already written a pretty thorough takedown of the article and I basically agree with what he has to say and will say somewhat similar things. Still, seeing as the article was a reply to me, I thought I’d invoke my right to reply, because the article is just filled with confusion. Lyman seems otherwise pretty smart and interesting, so it’s a bit disappointing—a bit like deBoer’s errors surrounding effective altruism, made more disappointing by his being otherwise interesting. Lyman should know better.

He begins his article by describing me as “a young man online walking backwards into Calvinist Universalism by gradually conceiving of God as an ultimately simple utility monster.” I’d like to applaud Stone on one true statement: I am a young man. As for the rest, well, there happens to be an ample record in print contradicting it. I am certainly not a Calvinist and in fact, when I talk about Calvinism, the words idiotic and evil make frequent appearances. I am a universalist, though none of my reasons for believing in God have anything to do with the utility monster—seriously, what relation does this bear to any of my arguments? I don’t, for example, say that evil is justified because God is a utility monster who benefits more from our suffering than we are harmed—that would be unconvincing because God, being omnipotent, could be happy in other ways.

Why am I nitpicking the sentence? Well, I am annoyed by sentences like this. Sentences that sort of combine deep-sounding words, with the occasional literary reference, but make no sense and are false. I think people should write fewer of them.

Lyman early on in his article links to a piece of mine where I speculate on the bizarrely poor quality of the typical EA criticism. He doesn’t intend to comment on my arguments in that article (as that article wasn’t giving criticisms of the arguments but instead psychological speculation). Instead, he decided to offer “some novel arguments against effective altruism.” However, as we’ll see, they are not novel and are, in fact, arguments that I’ve addressed at great length in other articles. Stone’s first criticism is:

I am a sociologist, the most correct discipline. I decline to accept the notion that effective altruism is a set of ideas, certainly not ideas about effectiveness or altruism. The reason is simple: if I started a movement called “Goodness-ism” and started claiming all good things as mine, that would be a bit silly. Goodness-ism would be an empty concept. “Effective altruism” is like that. Just a pairing of two generally nice words in order to claim ownership of generally nice things.

If you just described your movement as goodnessism, that would be specious. But effective altruism is not specious in the slightest. There are particular, concrete recommendations about giving to effective charities, taking high-impact jobs, and so on. Now, you might think it sounds trivial but it’s not and is in fact done by almost no one.

What percent of the population has looked into high-quality research about the best charities? What percent of them have done moral philosophy to try to figure out whether animal charities are more effective than human charities? Most people treat charity the way one treats making friends—a purely subjective enterprise where the things you pick are whichever float your fancy. Most people hear a nice story on NPR about some group and give a bit there, without looking much into effectiveness. In the rare event that they do look at effectiveness at all, they use it as a ruling out criterion rather than a ruling in criterion. They do five minutes of googling to see that the charity isn’t secretly funneling money to the mafia or run by satanic pedophiles who spend all their money on overhead (paying other satanic pedophiles).

Effective altruism advocates looking extremely carefully before one gives to charity. Don’t just give wherever floats your fancy. For example, don’t give disaster relief—it’s generally not effective—give malaria nets instead.

Take the situation when it comes to animal welfare organizations as an example. Very obviously, if one cares about effectively helping animals, they should care about the factory farms that torture many tens of billions of them. Instead, almost all money given to animal charities goes to pet charities. That’s not because people crunch the numbers and conclude that pet charities are more effective—it’s because they see an advertisement for a cute puppy on the television and give there, without looking into effectiveness.

Everyone seems to make this criticism of EA, that it’s really trivial. And yet it’s completely ludicrous. Something can’t be trivial if it’s opposed by a significant share of the population and done by only a few thousand people worldwide. Even if it’s trivial, well, Mother’s Against Drunk Driving is pretty trivial—no one is for drunk driving, and yet that doesn’t indict the movement.

Stone then clarifies his definition of effective altruism, writing:

Instead I will define effective altruism in terms of a social body which is aphilosophical. Effective altruism is simply whatever is done, stated, and believer by people who call themselves and are called by others “effective altruists.”

Suppose a bunch of satanic pedophiles (wow, they’re really making a lot of appearances in this article) started raping children and saying they were doing it in the name of effective altruism. Would that be an indictment of effective altruism? No—you should still do the things recommended by mainstream EA orgs—donations and so on—and just not be a satanic pedophile.

I propose, as I have before, distinguishing between effective altruism as a movement and as a philosophy—the philosophy is the one geared towards doing good effectively, the movement the real-world group of people who call themselves effective altruists and are widely agreed to be effective altruists by the rest of effective altruists.

Now, suppose that you are convinced that the movement is bad—maybe you object to animal welfare and think that it’s good when animals breathe in shit in tiny cages because it toughens them up, preventing them from becoming weak and feminine—back in my day, we all were in tiny filth and feces ridden cages for many hours and we didn’t complain.

Even if you think that, the way you live your life should be majorly affected by the philosophy. Even if you don’t think that giving to animal charities is desirable, giving to some effective charities is still good. So even if most of the movement is bad, how one lives their life should be profoundly shaped by considering the ideas of effective altruism, particularly if, as Lyman claims to, one finds the ideas trivial.

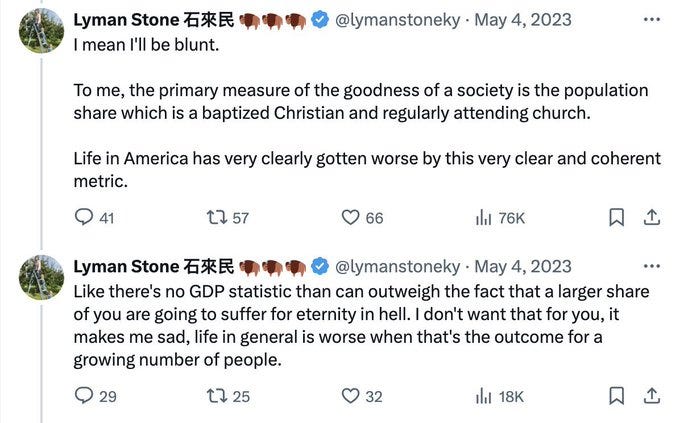

For example, Lyman suggests that the health of a society is determined almost exclusively by the number of Christians.

I find this very implausible, of course. But if one’s convinced by it, then shouldn’t you be looking into maximally effective ways of getting people to heaven? If some people might be tortured forever, making sure they don’t get tortured forever seems unbelievably important. So even if you have weird views about what matters, you should try to pursue them effectively.

Lyman next argues that places with more effective altruists don’t have more charitable donations than other places. Now, I don’t have anything to add to what Scott said—there aren’t enough effective altruists for them being in an area to have a big effect on average charitable giving and we have direct evidence that EAs give more to effective charities than others. He also worries that EAs give to a bunch of orgs, rather just a few—again, I have a lot to say about this, but it’s all been said by Scott, so read his piece. In short, different EAs value different things and have different beliefs, which explains why they give to a big range of areas, albeit still much smaller than the general population. The orgs EAs givec to are the ones that might be, on some view held by some EAs, one of the best charities—different people with different views will disagree about which ones are the best.

Okay, I’m starting to realize that most of the points I want to make have already been covered by Scott. I guess I’ll just cover the stuff he didn’t cover.

Lyman argues that actions to stop malaria done by EAs are not effective. He does this by…pointing out that malaria deaths stopped going down around 2015 which was one year when EA started to get big—though it has pretty considerable growth in other years. But this is very poor data. EAs are only responsible for a small share of antimalarial action! We wouldn't expect EA—a drop in the bucket compared to other forces—to have much of an effect compared to the combined impact of everything else in the world that affects malaria rates. What’s the plausible scenario for EA orgs increasing malaria? They distribute antimalarial bednets that have been shown to work by very high-quality randomized control trials (rather than sloppy correlational data that doesn’t even adjust for cofounders).

Lyman next worries that EA’s research into high-quality studies isn’t useful—we could already know the stuff from back-of-the-envelope calculations. But this isn’t true. It’s often very non-obvious which charities are the most effective. I have no intuitive sense of the effectiveness of the Shistomiasis control initiative—that’s why we need data on this. And if billions of dollars at stake, having high-quality data is important.

It’s ironic that Lyman criticizes EA for relying on poor quality data and supports back-of-the-envelope calculations when his method of statistical analysis of EA is just analyzing the bare correlations between EA and random things that one wouldn’t expect to correlate with EA much because so many other factors are much more consequential. Next, he says:

The first bullet point is highly conventional charitable activity. My view is everything in that category we can basically cross of the list of “unique features of effective altruism that might make us prefer it over other putatively benevolent social groups.” Everybody does that stuff. My church does that stuff!

I’ll take Lyman’s word that his Church does that stuff. But virtually no Churches look into effectiveness, in great detail, relying on high-quality randomized control trials. Everyone wants to help the poor, but its the EAs who do the nerd data analytics to make sure we’re helping the poor maximally effectively.

Lyman notes finally that EA encourages people to care about animals. It regards many billions of chickens living miserable lives as very serious because it causes, you know, more suffering than has been experienced in human history, every few years. Note, if you don’t think this is true then you can still be an EA—just take a job and give to charities helping humans, rather than animals.

But I do think that there are some number of shrimp that matter more than a human (and certainly some number of pigs that matters more than one human). If one takes seriously the obvious truth that suffering is bad, then they should be concerned about the cause of such tremendous suffering. Lyman doesn’t think we should be concerned about this, when we could help suffering humans instead, saying:

EAists sincerely believe that there is some number of shrimp lives that is worth more than a human life.

I do accept this, and in fact have an argument for this!

We didn’t evolve from shrimp, but let’s pretend that we did to make the math easier (you can replace shrimp with things that matter as much as shrimp). Let’s imagine that there are 1,000,000 generations between us and shrimp. Here’s a plausible principle: no generation mattered infinitely more than the one before it. Here’s another: if A matters more than B which matters more than C then A matters more than C.

But from these, the conclusion Lyman objects to that “there is some number of shrimp lives that is worth more than a human life” inevitably follows. The shrimp were not infinitely more important than the generations before them. Let’s imagine that each generation is twice as important as the one before it. This would mean that one of us is as valuable as two people in our parent’s generation (this is an oversimplifying assumption that dramatically undersells the importance of the shrimp). The 2 people in our parents generation are as valuable as 4 people in the generation before. Keep iterating the process and eventually you get that one human is as important as 2^1,000,000 shrimp.

Now, maybe you object that this shows that some number of shrimp matters more than a person, but it has to be a ridiculous number like 2^1,000,000. But, well, we’ve now established that some number of shrimp are more important than a person. Beyond this, it’s hard to have an intuition about how many it would be. If Lyman’s argument against any view that says that some number of shrimp matter more than people, well, if my modest principles are right, then we have independent reason to accept this allegedly surprising conclusion.

Here’s another reason to think that shrimp mistreatment globally is worse than one human death: pain and suffering are bad! Their badness doesn’t depend on how smart the sufferer is—we don’t think that it’s considerably less bad when dumb people get headaches than when smart people do. Even severely mentally disabled people’s pain is as morally serious as other people’s.

So then if this is true, and there are tens of billions of shrimp being mistreated, this is a truly staggering quantity of suffering. It might be more than is experienced by humans—I show that fish together suffer much more than humans. So then shrimp farming is only as bad as something would be if it caused more suffering to humans than humans have ever had. But that means that shrimp farming is one of the worst things in the world.

I agree this is a bit counterintuitive. But, well, is it any surprise that our intuitions would be screwed up when it comes to weird-looking creatures that arouse no empathy from us?

And what is it about shrimp that makes them so unimportant? It can’t be what they look like—that’s obviously not morally relevant. It can’t be their intelligence—even a human as unintelligent as a shrimp would be very morally important, and their suffering would be serious. So what is it supposed to be?

It’s important to understand this precisely. Most of us humans regard animal suffering, especially of vertebrate mammals, with sympathy. Psychologically this isn’t a mystery: vertebrate mammals (and many other creatures but especially vertebrate mammals) have a lot of shared-in-common visible responses to pain and discomfort and so we recognize the pain of other creatures, which hacks our empathy mechanisms which are adapted for intragroup bonding among humans, and causes us to feel for the animal a similar, if perhaps not always as acute, feeling as we would for a suffering human.

It’s important to grasp that this behavior is, in evolutionary terms, an error in our programming. The mechanisms involved are entirely about intra-human dynamics (or, some argue, may also be about recognizing the signs of vulnerable prey animals or enabling better hunting). Yes humans have had domestic animals for quite a long time, but our sympathetic responses are far older than that. We developed accidental sympathies for animals and then we made friends with dogs, not vice versa.

Isn’t Lyman a Christian? I assume so, as he thinks non-Christians go to hell. Extramarital celibacy is, in this sense, an error in our programming! It decreases one’s survival. We developed our ability to do calculus and think about the suffering of the poor on the other side of the world as a side effect of our genes concluding that it was conducive to us getting laid. That doesn’t mean we should throw out morality (particularly if one thinks we’re rational creatures made in the image of God, capable of grasping the moral law with our intellect).

My view though is the virtue ethics position is actually the correct one for most people. Mostly we dislike animal-torturers because animal-torturing causes us a lot of displeasure and discomfort and disgust, and we observe that since it doesn’t cause the animal-torturer that feeling, the animal-torturer is not One Of Us, he inhabits another moral tradition or moral world not reconcilable to ours, and so we are opposed. Virtue ethics works as an account because it explains how human moral communities actually form: mostly around personalities, social groups, kinship, etc, rather than pure ideas. Our moral functions are mostly about recognizing the group.

RESUME

I’m going to say this in all caps for the people in the back: VIRTUE ETHICS IS NOT JUST WHAT YOU GET WHEN YOU CARE ABOUT BEING VIRTUOUS.

It’s also extremely implausible that the only reason not to mistreat animals is that it makes us upset. To see this, imagine that an animal burns to death in a forest. No one ever finds out. Question: is this bad? If the answer is yes, then the badness of animal suffering can’t be about it making us upset.

There are lots of things that exhibit that a person is not one of us but aren’t morally wrong. Speaking up against slavery was, in societies with slavery, a good way to signal you aren’t part of the society—a good way to get excised. Nevertheless, it was obviously morally right!

I’m not saying our morals should be that way, just that they are that way. Humans are group reasoners, and in the vast majority of cases will subordinate their individual moral calculations to leader effects, collective decisionmaking, or peer pressure. Far from treating this as some kind of aberrant irrational behavior at odds with our moral functions, we should take seriously the possibility that this actually is an intrinsic element of our moral function, and that all our moral beliefs are in some sense efforts to look into other peoples’ hearts and guess if they are One Of Us.

And this gets back to animals. Many of us dislike wanton cruelty to animals and favor measures to prevent it, like banning cockfighting or something. But the reason we dislike this cruelty for most of us is not actually about the theoretical notion of the severity of the animal’s pain, but the extremely obvious notion of the torturer’s perverse glee.

Well I have now given several arguments for why we should take animal suffering seriously. Species is clearly not a morally significant category, and our moral consideration for another shouldn’t depend purely on tribalism—whether they’re one of us.

But imagine that animals were being tortured not for any sadistic pleasure. Imagine a person burned live cats for fuel. Assume that this was a slightly more efficient fuel source. This would obviously be deeply evil, even though no sadistic pleasure would be derived from the torturer’s perverse glee.

Finally, Lyman suggests that effective altruists should start trying to maximize getting into heaven by prostylletizing and killing babies (for then they go to heaven, you see). I think the odds that having Christian beliefs are necessary for salvation are so low, and that there are potentially infinite rewards from, for example, the eternal connections forged between us and those we save outweigh the benefits of getting people to believe certain doctrinal claims. As for his claim about killing infants to get them into heaven, well:

This won’t move most EAs, who don’t believe in heaven.

God puts us on Earth for a reason. Given this, he thinks us being on earth is better than us being in heaven. If this is so, then one shouldn’t kill people.

Killing people might be infinitely wrong, in which doing so isn’t worth the potentially infinite rewards.

We have very strong moral intuitions against killing. If you believe in God, he gave those to us, so probably we shouldn’t go around killing.

Generally, if you find yourself concluding you should kill babies, you should think you went wrong somewhere. That’s more likely than that you should actually kill babies.

EAists usually don’t actually tell us a welfare function. How many shrimp lives do equal a human one? Give me a number. Your value system requires you to have a number there. Let’s come up with a list of 500 bilateral trade relationships of what EAists would be willing to trade for what, and then spot how many of those lists result in non-transitivity!

The question is ambiguous. I think what matters is the balance of welfare, and that shrimp experience suffering probably around 1% as much as people (based on similar animals), but it’s hard to know. But you don’t have to have an exact number to intuit that saving many tens of thousands of shrimp from very extreme suffering is more important than saving a life—it’s probably not more than a thousand to 1.

Lyman finally (before closing out his article repeating the claim that EA is trivial and like other groups) says:

Where Bentham’s Bulldog is correct is a lot of the critique of EAists is personal digs.

This is because EAism as a movement is full of people who didn’t do the reading before class, showed up, had a thought they thought was original, wrote a paper explaining their grand new idea, then got upset a journal didn’t publish it on the grounds that, like, Aristotle thought of it 2,500 years ago. The other kids in class tend to dislike the kid who thinks he’s smarter than them, especially if, as it happens, he is not only not smarter, he is astronomically less reflective.

As Scott notes, this is ironic coming from someone who wrote an article rehashing old critiques of EA that have been given a thousand times, ignores the responses given by EAs, and quite literally declares that he’s giving “some novel arguments against effective altruism,” while misunderstanding morality, evolution, correlation, and almost every other topic he discusses. The only original bit of his article is his suggestion that EAs do terrorism and kill babies if they’re so committed to their principles.

It’s true that there were some people trying to do good effectively before EA. But EA is a unified movement of people trying to do this, one which has incorporated many of those that came before it. Peter Singer predated EA, but he was basically just doing EA before it was an organized movement.

Imagine I started a group of progressive Democrats trying to get stuff done. If I clarified that this was what the aim of the movement was, this wouldn’t be claiming that I’d invented progressive politics. It would instead be the claim that a movement working on those things was important and that there should be more of it at the margins.

Just as that progressive group would neither be wholly original nor what everyone else is trying to do, the same is true of EA. But EA has had major wins, saving many tens of thousands of lives, improving the conditions for huge numbers of animals, and so on. While one can have philosophical disagreements at the margins, taking effectiveness seriously should change how one lives to a significant degree.

It’s been a running theme in this article that I’m basically just saying the things that Scott said. I think that those criticizing the critics of EA are usually pretty similar. That’s because the criticisms make extremely basic errors. Just as two mathematicians will have the same criticism of a failed proof, so too will most of the criticisms of EA criticisms be pretty similar.

I don’t say this lightly. The only areas that attract these completely confused criticisms seem to be veganism and effective altruism. On other topics, while people often disagree with me about things, the critics aren’t across the board, foundational confused. Torres has made a career out of being confused about EA, and for many others, it’s pretty profitable.

I would suggest that before someone else publishes an article calling EA trivial and unoriginal, they should take a few days to read the things EAs have said about those criticisms. Otherwise, they will continue to make these same extreme errors.

Imagine accusing someone of "conceiving God as an ultimately simple utility monster" and also claiming that the only thing that matters is how many people are Christians because everyone else are doomed to eternal torture.

Imagine actually believing that God sends every non-Christian to eternal Hell and also thinking that this God deserves worship, and is basis for all morality. And then having the audacity to mock people that care about animal suffering.

Personally, I don't find arguments in favor of shrimp welfare at all persuasive and think probability that shrimp experience any qualia at all to be absolutely tiny (contrary to, say, probability that pigs have subjective experience which is around 50%). But I can see where people who care about shrimp welfare are comming from. That it's a question of different probability estimate about a complicated question without a very clear answer yet. Not overal moral or epistemic brokenness.

I don't see how one can worship a God of Eternal Torture without being deeply broken in some sense.

I would love for you to make a post about what you think the weakest points of EA are -- in terms of philosophy, practice, culture, and everything else.