What You Need to Refute Arguments With Astronomical Stakes

A merely pretty good rebuttal isn't enough

Most arguments don’t have very important implications even if they are correct. For example, it’s probably bad to litter, but there’s no way that littering is the worst thing you are doing (unless you’re shockingly prolific in your littering or shockingly otherwise saintly). But some arguments, if true, have huge implications. This is because they imply the existence of very weighty reasons to either perform or refrain from an act. Some examples:

The basic argument for veganism goes: over the course of your life, by eating meat, you will cause animals to endure hundreds of years of excruciating torture. Because suffering is a bad thing, causing incomprehensible quantities of it is extremely terrible—to quote

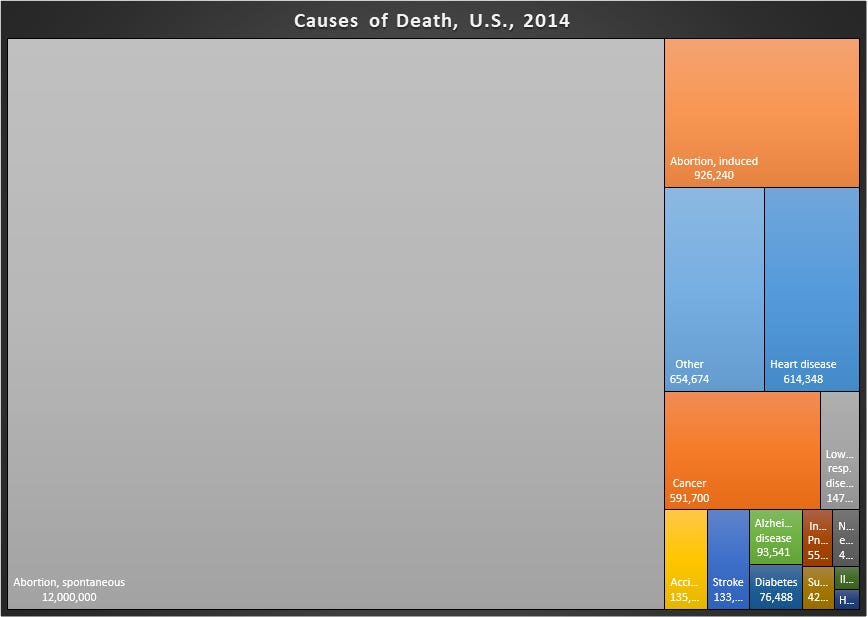

“It’s better to commit a thousand microaggressions than to buy one McDonald’s hamburger.” If you eat meat, the argument goes, you cause more suffering to animals than all but the worst serial killers cause to humans over the course of their life. If you compare aggregate farm animal deaths to human deaths, you get a chart like the following—all human deaths are a rounding error:

The basic argument for giving away a lot of your wealth goes: there are people suffering and dying whom you could save for just a few thousand dollars. Failing to save them is about as wrong as failing to save a child drowning in a pond, when wading in to save the child would ruin your suit. Thus, we all ought to give vastly more than we do. And perhaps the obligation is even clearer in the case of animals, because you can prevent many years of animal suffering per dollar (and potentially thousands of years of insect suffering per dollar). If a chicken was going to be trapped in a cage for a year unless you spared a dime, it would seem obvious you should spare the dime. Failing to donate to animal charities, the argument claims, is similarly bad.

The basic argument for Longtermism is that in expectation nearly all people—well above 99.9999999999999999% of expected people—will exist in the far future. Their interests matter (why in the world would their temporal location affect their moral worth?) If this is right, then by far the most important impacts of our actions are in the far future. We should do all we can to make the far future go well. What we do to benefit people alive today is a rounding error compared to this.

The pro-life argument says that life begins at conception. Thus, abortion kills someone. It is morally no different from infanticide. On the pro-life view, murder is presently legal so long as the victim is young, and millions of innocent babies are routinely butchered. The graph below illustrates just how terrible prenatal death is if the pro-life position is right.

Lots of religious people think that believing in their religion significantly reduces your probability of going to eternal hell. Thus, drawing converts is infinitely important. While heads of EA charities might toss around claims like “14,000 welfare improved years for insects per dollar,” (when trying to pick up girls at the bar) many religious people think money spent on evangelism improves infinite expected life years per dollar!

Now, as it happens, I don’t buy all these arguments. While I think the first three are very likely correct, I pretty strongly reject the idea that early stage abortions kill a person, and I think eternal hell is nuts. It might be that being religious improves one’s prospects for getting into heaven quickly, and thus has infinite expected value that way, but then a lot of other actions that improve one’s character also have infinite expected value. Without infernalism, the case for evangelism being the top priority is a lot weaker.

But my aim in this article isn’t really to discuss the merits of most of these ideas. It’s instead to make the following point which I take to be rather trivial but which people often seem not to appreciate: if an argument has huge implications if it is right, then for it not to have enormously important implications, you must be extremely certain that it is wrong.

Let me start with a simple case. Before the first nuclear bomb was detonated, the Manhattan Project researchers apparently thought there was a non-trivial chance that it would ignite the atmosphere and destroy all life on Earth. I think it’s clear that even after being pretty sure that this isn’t going to happen, unless you’re near-certain, you shouldn’t risk detonating a nuclear bomb. Similarly, if there’s a plausible case to be made that some chemical will wipe out all people on the planet after seeping into the groundwater, it isn’t enough to be 80% confident that the case is false. You need to be near certain to justify the use of that chemical.

Let’s apply this to ethics.

Start with meat eating. The claim made by vegans—many of them philosophers, many of them quite smart—is that eating meat is extremely terrible. It is much worse than keeping five puppies caged in your basement and torturing them. Barring weird ways that our actions affect huge numbers of wild animals, it is the worst thing you do routinely unless you’re a serial killer or prolific child rapist.

Now suppose I make that case to you. You reply by giving an objection like the causal inefficacy objection, which says that by consuming meat, you don’t actually have an impact on meat production. Thus, meat consumption doesn’t cause any extra animal suffering and is fine. Maybe you also claim that because animals do not possess rational souls, their interests aren’t very important.

I’m not moved by either of these arguments.1 I think there are pretty knockdown objections against them.

But there’s a more general point, a deeper way in which these arguments miss the point. Both arguments are extremely controversial. Many informed philosophers and economists reject them. There is, in fact, an extensive literature disagreeing with them.

Maybe you’re even 90% sure that one of them is right. But still, that means that you are risking a ~10% chance of doing Ted Bundy-esque levels of evil because you like how meat tastes. That is a moral failing.

If an argument is important if true, then you don’t even have to be very confident that it is true for it to have important implications. Even a low chance that it’s true should be enough to make your behavior change. Merely giving an objection is not enough. To have license not to act on potentially hugely important moral arguments, you can’t just be uncertain about whether they’re right. You must be almost certain that they’re wrong. There must be an argument so powerful that it reduces them almost to the point of absurdity.

I remember someone recently making the case that you shouldn’t give to shrimp or fish because she thought they weren’t sentient. As it happens, I strongly disagree with the factual claims underpinning this argument! I’m probably about 75% sure fish feel pain, and a bit above 50% that shrimp do.

But what I thought was particularly wrongheaded about the argument wasn’t the first-order judgment that these creatures probably don’t feel pain. Instead, it was the idea that one could be confident enough in this judgment to license ignoring their interests—and not, for example, spending a dollar to spare more than 10,000 shrimp from excruciating agony.

Even if I became as confident that fish don’t feel pain as I currently am that they do, that wouldn’t really affect my behavior. Even a 25% chance that trillions of beings are in exquisite agony as they suffocate to death—that more than a hundred billion conscious fish suffer every moment of their existence in unnatural nightmare facilities where they’re starved, afflicted by disease, and kept in stressful and unnatural conditions—is enough to make this a pressing problem.

A problem doesn’t need to have more than 50% likelihood of being serious to be worth acting on. If there was some war that only had a 10% chance of going nuclear and ending life on Earth, that would be quite serious, even though there’d be 90% odds we’d be safe. Risks of extremely bad things are worth taking seriously.

I find this mistake especially common when people are thinking about Longtermism.

The potential amount of value in the future is incomprehensibly large. Nick Bostrom once estimated that the number of digital minds that could be sustained in the far future was 10^52, each of them living 100 years. Even a small chance of affecting such astronomical quantities of value is worth acting on (and see here for why risk aversion doesn’t help avoid Longtermist results).

Plausibly taking some high-impact jobs could reduce risks of human extinction by more than one in ten million. This strikes me as a very conservative probability estimate in light of how few people there are working on the world’s most pressing problems. For example,

is one of the only groups on the planet seriously planning for how the world can navigate a post-AGI world without an exclusive focus on alignment. Almost no one is seriously preparing for the biotechnology of the future that experts think has a several percent chance of ending the species this century.Reducing risks of human extinction by one in ten million saves 800 lives in expectation (and see Carlsmith’s excellent piece for more details on why multiplying probability of impact by impact is the right way to calculate the moral value of your actions or here for my much longer defense). So just taking into account lives today, taking one of these jobs is about as good as saving 800 people. That’s better than almost any other job you could take.

But that’s just considering the lives around now. If we take into account the number of future lives, things get bonkers. Suppose we think there is a 1/1,000 chance that Bostrom is right about the size of the future. This strikes me as very conservative, as the number of future people could be much larger than we expect—the odds are well above zero that the number of future people that could be sustained is many orders of magnitude larger than Bostrom’s estimate.

This would mean that by taking one of those jobs, you save, in expectation, 800 current lives, and bring about the existence of 10^42 extra expected lives. That’s insane! That means your expected value personally could be greater than all the value in human history so far. I’ll even be generous and ignore the way that this quantity of value is potentially supercharged to infinity by theism. Even if you think my estimate is off by ten orders of magnitude or so, the value on offer is still incomprehensible.

So what are the arguments that people make in response? The most common argument goes: maybe we can’t influence the future.

And sure, maybe we can’t. Maybe the people who endorse cluelessness are right and our actions can’t make the future reliably better (though not likely). But are you really willing to bet 10^42 expected life years on that proposition? Are you really willing to gamble all that expected value on a speculative philosophical proposition like moral cluelessness?

This is a point that I feel people don’t internalize when discussing hugely important topics. I hear a lot of discussions about these topics where one person will raise a point that has earthshattering implications if it’s true. The other person then will proceed to give some kind of mediocre but not obviously wrong objections. Both sides will discuss for a while, and third-parties won’t find it clear who is more persuasive. In a situation like this, the first person is always more persuasive. If a conclusion is even remotely plausible and has implications as staggering as Longtermism does if it’s true, then it should affect how you live.

This is not, of course, to say that just because you can’t beat someone in a debate, you have to take seriously their crazy idea and act on it provided it has important potential implications. Some views are ridiculously implausible even if you couldn’t out-debate some of their advocates. I’d probably lose a debate to lots of people who believe in crazy conspiracy theories with existential implications, but I don’t take those seriously. My argument is not “you have to take seriously every position that you can’t win a debate against,” but instead “you have to take seriously every position with huge implications provided it is not extremely implausible.”

It would be like if someone was playing around with a switch that had some chance of launching the entire U.S. nuclear arsenal. Even if you have pretty good arguments for why the switch isn’t connected, you had better be pretty flipping sure (pun intended) of that before playing around with it. Earthshattering revelations have to be very clearly wrong to not be earthshattering.

But with this out of the way, it seems like the case for Longtermism is quite decisive. Remember, the basic argument for strong Longtermism (the idea that the future going well matters vastly more than the present going well) just rests on two premises:

Helping some particular future person is at least within a few orders of magnitude as important as helping some particular present person.

Nearly all people who will exist in expectation will be in the distant future.

As far as I can tell, those who reject Longtermism don’t really reject either premise. They mostly are skeptical about the prospects for making the future better in the ways Longtermists want to, or about the enterprise entirely. But for the reasons I’ve been saying, merely decent skeptical arguments aren’t enough. You have to have a 10 kiloton nuclear bomb of an argument against the possibility we can influence the future for it to have any weight against the enormous potential expected value. But those who oppose efforts to make the far future better—by, for example—reducing existential risks, don’t have anything of the sort. By my estimation, they don’t even have good arguments.

Now, one can haggle over exactly which values should be promoted in the future. Maybe, for example, you don’t think creating happy people is a good thing, so you don’t care much about maximizing the number of happy people in the light cone. Now, cards on the table, I don’t think this view is at all plausible for reasons I’ve given here; I think there are pretty knockdown arguments for the conclusion that filling the light cone with happy people would be great!

But still, even if you have this view, you should be a Longtermist. You should strongly support actions that try to prevent astronomical future suffering. Maybe you’ll disagree with traditional Longtermists about which futures we should promote, but you’ll still agree that we should try to promote far future value. No matter which values you think we should promote in the future, so long as you think some futures are better than others, making the future go well is still astronomically important.

I fear this has been a bit meandering, so let me try to summarize my argument as simply as possible. Longtermists say that we should try to make the far future go well because it has so much more value than the present. There are a few main ways people go about rejecting it. A first is to deny we can influence the future, but that won’t work because even a tiny chance we can influence the future is enough to make a strong case for Longtermism. This first reply doesn’t take seriously enough the astronomical stakes.

Another major way people object to Longtermism is by suggesting that we have no moral reason to create lots of happy people. This is philosophically dicey, but more importantly, it isn’t actually an objection to Longtermism. You could think creating happy people wasn’t important at all and still be a Longtermist, so long as you thought avoiding bad futures was important. In addition, even if you’re not sure if creating happy people is good, if there’s a low chance that it is, then futures full of happy people are valuable in expectation. Even a mere 5% chance of an incomprehensibly unfathomably awesome utopia is worth striving to create.

Now, you can try to avoid this by being risk averse, but that won’t really work on the leading accounts of risk aversion, especially if you take into account the chaotic effects of our actions. It also runs into very serious philosophical problems. Even if you can discount extremely low risks, probably you can’t discount risks of like one in ten million—it would be immoral to play Russian Roulette with the fate of the world if the risk of disaster was one in ten million. People who dedicate their lives to reducing nuclear risks, and reduce risks of an existential nuclear war by one in ten million aren’t wasting their lives.

In short, when you take stock of just how important Longtermism is if it’s right, it becomes pretty clear that it should influence your decision making. Even if you’re uncertain about it, when some view implies you need large exponents to write out the expected value of your actions, you should take it very seriously. Longtermism isn’t alone in being worth taking seriously even if you’re unsure about it, though I think the effect is particularly marked because of the sheer extent of the stakes. Longtermism is the most important stop on the crazy train, the one whose potential implications dwarf all others—potentially by many orders of magnitude.

If a person gives you an ordinary moral injunction, you can mostly shrug it off if you have objections that you think are pretty good. But if they give you one with potentially earthshattering implications, then to ignore it, you need very strong reasons. You must be extremely confident that it is wrong to ignore it. And note: the fact that an argument would have annoying practices consequences or be sneered at by your ingroup is not a very strong reason. I suspect that one of the most serious moral failings people make routinely is failing to take seriously the conclusions of arguments that have enormous implications if they are correct.

If you buy what I’ve said so far, then you should start being a Longtermist. You should give to very impactful Longtermist organizations and think seriously about getting a job that has some chance of increasing making the far future better (if only by making us less likely to go extinct). The 80,000 hours career research guide nicely discusses some ways to decide upon a high-impact career, and their job board lists available high-impact job openings. By doing so, your expected impact on the world could be staggeringly massive.

In short, then, I’ve argued that conclusions that are big if true are also big if uncertain. This is an important insight for approaching lots of issues. But because Longtermism has the biggest implications of any idea that might be correct, and isn’t obviously wrong, you should take Longtermist considerations very seriously.

Interesting post: the generalized, finitary Pascal’s wager.

Isn’t it at least plausible (and indeed, widely argued to be the most likely case) that on a long-termist view the expected impact of the entire AI safety movement so far has been gobsmackingly negative, insofar as the movement seems to be causally responsible for the existence of OpenAI and Anthropic? Similarly, it’s at least plausible that bio-safety research programs lead to, for instance, lab leaks of horrifically deadly pathogens, as has indeed happened repeatedly. I think the consequentialist longtermism skeptic can much more easily argue that it’s really genuinely hard to calculate the expected sign of the impact than that the probability is small enough to ignore. The expected utility argument is not in itself convincing to a non-consequentialist, either, which makes it a bit strange that you don’t even mention this axiom. It’s certainly generally virtuous to do things that help lots of people, even if they’re far away, but I’m profoundly skeptical whether it’s virtuous to shoot while drunk at a target which your fuzzy eyes tell you is *likely* be an assailant but *might* be your own daughter.

Past people have often taken our lives in their hands in ways that in retrospect we find culpably ignorant, even if sincerely well-intentioned. I would suggest Lenin as an illustrative example here.

I think it is virtuous to avoid taking actions whose impact, though it may be large, is extremely difficult to predict in sign. There are always more robust actions available, and one can pray that a later person will be able to act from a position of more clarity. It is certainly possible to argue that you are actually the crux of history, and if you don’t act now, you can’t reasonably expect anyone else to be able to. But I think it’s very rarely true. Probably the Manhattan Project scientists are about the only people of epistemically grant this to, and even there it’s not entirely clear to me that there would be atomic bombs today if the US had held off then.

By the way, surely you’re regularly praying or attending church by now? It would be hard to even try to take this post seriously if you can’t take it even that seriously for yourself.

I think your positions on abortion and longtermism are inconsistent. Granting that abortion does not kill a person, it still is the case that it *prevents* a future person from coming into existence. But according to longtermism, this is just as bad as ending a life right now! If "temporal location" does not matter for moral worth, then it doesn't make sense to judge abortion based on the current lack of personhood of the fetus, rather than on the personhood of the human that would be born. In other words, abortion reduces the number of human lives that would be lived by 1, which should make it equivalent to homicide for longtermists (I'm not a longtermist myself, to be clear).