"The AI Con" Con

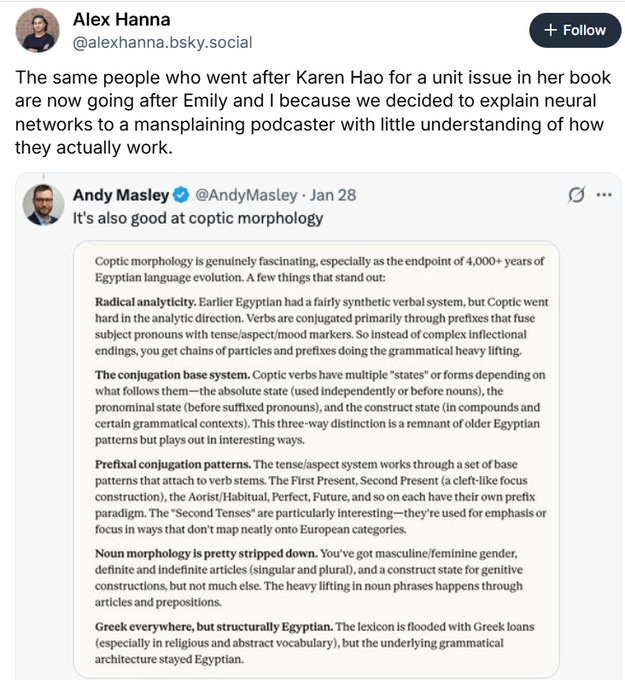

The shockingly terrible arguments of the AI naysayers

Reading Emily Bender and Alex Hanna’s The AI Con is like time-travelling back to 2020. Many passages are a stark reminder of the world of peak woke—they described Searle’s famous Chinese room argument as “an extremely othering way of making the argument.” More importantly, the picture they paint of AI capabilities would have been an accurate enough description of the AIs of 2020, but seemingly has not advanced since then.

Perhaps it is no surprise that the authors admit to not using the technology they discuss.

The Bender and Hanna (B&H) thesis is that AI is massively overhyped. That it’s a mostly useless technology with little upside and massive downside. It will devastate the environment, use up enormous quantities of water, exacerbate inequality, and so on, all without having any real benefit. It will not assist seriously with scientific advancements, nor will it be economically viable. The authors seem to curiously maintain the position that it will replace a number of jobs but won’t improve the productivity of jobs.

This position was not plausible in 2020, and has grown less plausible since, having had a head-on collision with the facts. AI can invent novel math proofs that impress the best mathematician in the world. It can automate away big chunks of coding. They can assist writing far better than a secretary. In seconds, by asking LLMs, you can get a detailed and well-researched answer with sources. They can almost instantly complete tasks that take people hours.

The AI Con is what you get when a thesis you’ve been stochastically parroting for years is decisively disproven by the evidence: it’s a desperate and error-filled attempt to rescue a deeply implausible thesis. Nearly everything in the book is poorly reasoned or misleading. It is also written with the confidence of someone expounding trivialities, rather than arguing for a contentious thesis. The authors rarely saw the need to respond to objections.

The best thing I can say about the book is it’s very well written. B&H are engaging writers. Some bits are quite funny (e.g. “Meta’s LeCun beclowned himself.”) I rarely found myself bored when reading (though this is perhaps because it is hard to be bored when encountering outrageous falsehoods on nearly every page).

The case for AI being a big deal is pretty straightforward. AI is advancing rapidly. It can already write better than most undergraduates, and possesses a great degree of general knowledge. In many domains, like chess, AI surpasses the best humans. If progress continues, it will be able to perform more and more useful tasks, until it can do most jobs better than people. Currently, the main things holding back AI from general employment are: 1) it can’t interface with the physical world; 2) it can’t really use a mouse, but just output text; and 3) it can’t do long tasks. But extremely rapid progress is being made on all these fronts.

Chapter 2 begins the main portion of their argument. B&H claim AI “doesn’t refer to a coherent set of technologies,” but instead “is deployed when the people building or selling a particular set of technologies will profit from getting others to believe that their technology is similar to humans.” This overlooks the important fact that virtually no words can be precisely defined, and that “a computer that performs cognitive tasks similar to those of humans,” is, in fact, a pretty good definition of AI. They suggest that a better term for AI would be “stochastic parrots,” or “a racist pile of linear algebra.” Okay.

They describe ChatGPT as “nothing more than souped-up autocomplete,” and cite as evidence that the words GPT outputs come from analyzing the relative propensity for words to go together. ChatGPT is designed to look at which patterns of words go after which other patterns of words. This is taken to prove that AIs are neither useful nor conscious.

And yet neurons work the same. Much concept formation in humans occurs through the associations between one set of neuronal activations and others. This is often glossed as “Neurons that fire together, wire together.” B&H also only look at the text prediction stage, and ignores the greater capacities that the AIs develop through reinforcement learning. What do B&H say about this crucial objection, that their criticisms of AIs being smart would also apply to humans. They say that it is racist:

But while AI boosters have spent time devaluing what it means to be human, the sharpest and clearest critiques have come from Black, brown, poor, queer, and disabled scholars and activists. These are the groups that have always been excluded by design from the category of “human”. But it is often precisely their expertise that is most needed, whether it is computer scientists like Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru highlighting that “AI” systems cannot “see” darker skin, or how transgender bodies are rendered impossible at airport security checkpoints and singled out for physical searches, as called out by design researcher Sasha Costanza-Chock. The devaluing of what it means to be human is apparent not just in the application of these technologies, but in their very conceptualization. Methods of defining and measuring intelligence have been more than complicit in this project; indeed, they were designed specifically to do such a thing.

Now, how anyone is supposed to find this persuasive is beyond me. The fact that AIs sometimes make mistakes analyzing darker skin does not, of course, tell us whether human concept formation is similar enough to AI that their arguments prove too much.

Bizarrely, this seems to be the authors’ go-to method for responding to claims that humans are like complex machines. When Robert Wright asked how they know that AIs aren’t conscious, given that, he claims, you can’t even really know if other people are conscious (at least with certainty), Bender replied that she doesn’t “have conversations with people who don't posit my humanity as an axiom of the conversation.” What a weird response. Many of the comments picked up on this:

The authors similarly declare, “Despite claims that machines may one day achieve an advanced level of “general intelligence”, such a concept doesn’t have an accepted definition.” But this is a very bad argument. The fact that it’s hard to define some property doesn’t mean it can’t be possessed. It may be a bit hard to precisely define the word explosion, but that doesn’t mean nothing can explode. Philosophers have no agreed-upon definition of the word knowledge, but this doesn’t tell us about whether humans know anything. Imagine arguing this in a courtroom: “Your Honor, I couldn’t have murdered the defendant—there’s no agreement about the definition of murder!”

They then spend a significant amount of time smearing IQ by discussing its supposedly racist origins. This is obviously irrelevant to assessing whether it’s a good idea—Planned Parenthood was invented by a eugenicist, but this tells us little about whether it’s a good institution. They never discuss the extreme predictive success of IQ, which correlates with a number of important life outcomes. General intelligence is simply the ability to reason well across a number of cognitive domains. AI already has some degree of general intelligence, and its capacities are only going to increase.

B&H similarly declare it eugenicist to be concerned about low birth rates:

Tesla and X/Twitter owner Elon Musk has repeated common eugenicist refrains about population trends: notably, claims that there are not enough people and that humans (particularly the “right” humans) need to be having children at even higher rates. In August 2022, Musk tweeted, “Population collapse due to low birth rates is a much bigger risk to civilization than global warming.”

The term eugenics has lost all meaning. Apparently if you think it’s good to be alive, and so a world population dwindling into non-existence would be a bad thing, you are akin to those who carry out forced sterilization. Similarly, the authors describe Richard Hanania as “a right-wing political scientist who has expressed explicit support of sterilization of those with low IQs and warned against “race-mixing.”” It seems worth mentioning that Hanania expressed these views about a decade ago, and has strongly repudiated them—and, in fact, now spends his days as a sort of heterodox resistance lib going off on right-wing stupidity and supporting mass immigration!

B&H strangely declare, “despite what many of the AI boosters would have you believe, large language models and text-to-image models have not been easy moneymakers. OpenAI’s big bet has been to sell their tools to other businesses.” But if they make billions in profit from selling them, that sounds like being a money-maker? Similarly, they have a section titled “AI Is Always People,” and their evidence for this is that some brands of self-driving cars have human oversight. At most this seems to justify the claim that “AI is SOMETIMES people.” A universal generalization is not confirmed by a single example. Precision and lack of hyperbole is not a virtue of the book.

The next chapter discusses downsides of AI as used by healthcare workers, the legal profession, and more. What is oddly ignored is the upsides in these cases. The authors discuss privacy concerns from AI being used in healthcare, and yet ignore the obvious upsides of allowing people to quickly have high-quality healthcare information. Chatbots are remarkably good at advising one what to do in the case of a healthcare ailment. The authors express concern about AI therapy, noting that the AI sometimes gives bad advice, but ignore the possibility of AI being used to give good advice. Sober analysis requires comparisons, not just a catalogue of grievances.

The authors then discuss AI being used to produce slop blog articles and fill in for authors of books. Yet this seems oddly inconsistent with the core thesis. It cannot be both that AI can nicely replace writers and that it’s useless. If AI produces useless slop, then how is it replacing writers?

Chatbots are described as “only linking together word patterns they’ve calculated from their training data.” Yet human neurons also follow deterministic physical laws. The brain is also exhaustively computationally describable as a relationship between inputs and outputs.1 If AIs can invent new math proofs, for example, or give takes on philosophical arguments that no one has ever thought of before, then it seems that they have at least the minimal kind of creativity needed for their being economically impactful.

How the authors treat the possibility of AI speeding up scientific development is relatively typical. They first give an example of an unsuccessful attempt to use LLMs for scientific research. Yet that doesn’t prove anything, any more than the fact that some people failed to invent airplanes means that humans would never be able to fly. They then claim, “the allure and prestige of AI raise the risk of narrowing fields of inquiry to those questions which can be approached with these tools.”

But this is a fully general argument against any new way of doing things! There’s always concern that the new method will be used as a crutch and will crowd out old methods. Perhaps solar development is a bad thing because it might crowd out other forms of renewable energy. There are obvious and major upsides for the scientific process from AI that can automate away the role of a scientific researcher. They next claim:

At the same time, the imagined tools represent the epitome of a view from nowhere, or the idea that one can have objective knowledge of a set of truths, uncolored by their personal experience. At this historical moment where science is finally starting to grapple with the idea that the standpoint of the scientist matters, we should rather build diverse communities of knowers. Western ecologists, for instance, have begun to learn something that Indigenous communities have known for a very long time: to control wildfires and maintain healthy local plant and animal ecologies, humans need to conduct controlled burns of forests and areas with overgrowth.

Certainly personal experience can give a person some information that they wouldn’t otherwise have. But obviously this doesn’t mean that gaining access to objective facts isn’t useful! People would have been better off for most of history if informed about the germ theory of disease, for instance, even though you become aware of things through experience.

As an aside, the idea they’re criticizing that “one can have objective knowledge of a set of truths, uncolored by their personal experience,” is conceptually confused. If all this means is that our knowledge of facts comes from our personal experience, well even that isn’t strictly true because we have innate knowledge. But surely there are some facts that aren’t objectionably colored by our personal experience. My belief that 3 is between 4 and 2, there are infinite prime numbers, various things exist, and the number of dogs in the world is more than 7 are not unduly based on personal experience.

Lastly, the authors claim “With systems trained on past data and practices, both shaped by far-from inclusive viewpoints, the visible possibilities are narrow indeed.” Now, again, I will just repeat: the complex patterns that you pick up from predicting text have uses aside from predicting text, just as the patterns evolution gave us to pass on our genes also allow us to do calculus. If AI is creative enough to do novel philosophy and math, why not novel science?

Perhaps there is something wrong with this argument. But it—quite an obvious reply—is not discussed. Nor is the past spectacular use of AI for scientific discovery. Similarly, it is quite a dangerous thing to naysay AI indefinitely based on the limited capabilities of current AI, just as it would be a bad idea to suggest that we’ll never go to mars based on the fact that we have not yet.

Chapter 6 discusses why the authors reject both AI doom and AI boosting. The authors start by summarizing the doom scenario as “machines become “sentient” enough to have their own preferences and interests, which are markedly different from those of humanity.” This is misleading; as basically every AI doomer has said many times, the AI doesn’t have to have consciousness to be dangerous. AIs are being trained to execute long-term plans. AIs that try to steer the world in some direction don’t need to have a conscious mind to kill you.

The authors explain why they don’t buy alignment saying “Embedded in the idea of alignment is a premise with which we fundamentally disagree: that AI development is inevitable.” But this is false. You don’t have to think that, say, development is bioweapons is inevitable to think that it’s worth having a plan for what happens if we develop bioweapons. The reasons they give are not any good either:

For one thing, what is currently being developed as “AI” does not work, nor is it helpful, for an overwhelmingly large portion of people living on the earth today, especially people in the Majority World. Furthermore, as we’ve said elsewhere, there is no clear, precise definition of AI. Nor is there any solid evidence that the work of AI research now (or of the past seventy years) is on a path towards that undefined destination. Lastly, the development of mass automation tools is not socially desirable.

But something can be useful even if most people don’t use it. Most people don’t use rockets, but they are still useful. This is also a curious complaint about AI, when about 15% of the world uses it! You don’t need a precise definition of AI for it to be developed. Reality is not constrained by how we use words. Surely there is some evidence that AI is on a path toward AGI—maybe the fact that it invents novel math proofs doesn’t settle the issue, but it’s surely some evidence.

And whether AI is inevitable is distinct from whether it’s desirable (a non-zero amount of hatred in the world is inevitable but not desirable). Advanced AI may have some downsides, but the enormous technological boom it could bring about also has some large upsides. It might accelerate anti-aging technology, for instance, or develop cures for cancer. The net impact of AI isn’t at all obvious.

If possible, things get even worse when the authors begin discussing Longtermism. They claim it has its “origins in the Anglo-American eugenics movement.” The only bit of evidence they cite is that Julian Huxley who coined the term transhumanism, was a eugenicist. Had a eugenicist invented the word “con,” this wouldn’t mean B&H’s book was mired in eugenics. They then claim:

For instance, one of the main arguments for longtermism is that, according to its utilitarian logic, we should discount current-day suffering because we need to optimize technological development to seed the environment for the trillions of future humans who will colonize space.

Please find me one Longtermist who has given this as an argument for longtermism! If anything, this would be a judgment that follows from Longtermism, not an argument for it. Yet as has been patiently explained by Longtermists over and over again, how we should steer the future is distinct from whether the future overwhelmingly matters. You could be a Longtermist who thinks there’s nothing good about creating happy people, but instead that it’s very important to make the far future go well for those who exist.

Their only objection to Longtermism is that it deprioritizes the present relative to the future. But they ignore the common replies: Longtermist interventions, using quite modest assumptions, are quite desirable by present lights. And if future people matter as present people do—if your interests matter even if you’ll be alive in 100 years rather than today—then sometimes it is worth prioritizing future interests over present interests. Noting that there’s a tradeoff between A and B isn’t an argument for prioritizing A over B, unless you give some reason why A is more worthy of promotion than B.

They claim “actually existing human suffering—borne primarily in the Majority World—is ignored for hypothetical threats of rogue algorithms,” even though Longtermists and effective altruists have been extraordinarily effective at reducing suffering in poor nations. Effective altruists have funded highly effective charities that save about 50,000 lives annually—most of them in poor nations outside the Western world. Also, as goes without saying, if AI kills everyone, or enables the development of existential bioweapons, this will be bad for those in the poor countries too!

The argument for Longtermism is very simple. The future will have lots of people. Future people matter. We can affect how well off they are. So we should try to make their lives go better. If future people matter as much as present people, then this judgment is quite sound—and our actions’ impacts on the far future matter far more than their near-term impacts. If only the authors had bothered to say where they get off the boat, instead of making vague innuendo about eugenics.

The authors suggest that AI doomers are making an extraordinary claim that requires extraordinary evidence. But what is so extraordinary about the claim? We are currently in the process of making very intelligent AI. There is enormous incentive to make an AI that can perform useful tasks. That this sort of AI could pose serious threats isn’t some ridiculously unlikely claim that should arouse extreme skepticism.

That, and repeating the canard about no definition of intelligence, are their only objections to the claim that rogue AI poses existential risks. This is not a serious treatment of the subject. You shouldn’t glibly brush aside the concerns of two Turing Prize winners—the computer science equivalent of the Nobel prize—without taking them seriously.

The authors then complain about the climate impacts of AI. They do this mostly by just citing the raw amount of energy used, and comparing it to other things. But it’s not surprising that a technology used by billions of people uses lots of power. If you prompt an AI 100 times, that will use about .1% of your daily power use. Compared to other activities we perform regularly, like driving, AI uses relatively little power (see here for more). Predictably, they also repeat the even more bogus water use canard—eating a single hamburger is over a million times worse for water usage than prompting AI.

So how, at a high level, do their claims hold up. The book, as I see it, makes three major claims:

AI is very bad near-term.

AI isn’t useful near-term.

AI won’t be a big deal long-term.

None of their arguments for these are persuasive. Their main argument against AI being useful is to claim AI lacks real creativity and is just a stochastic parrot. I’ve already discussed that argument. They list some real harms of AI near-term, but ignore the benefits. They have almost no arguments for why AI won’t be a big deal long-term, and nothing they say is persuasive. Most concerningly, they never discuss the arguments on the other side, nor the common objections. If you’d like to learn about the quality of AI, or even the best arguments for why AI won’t be a big deal, I would recommend looking elsewhere.

As it happens, I think we have an immaterial soul that allows us to grasp non-natural facts, but AI doesn’t need that to pick up the pattern of human judgments. AI can be trained to know the mathematical and moral facts, without having to invent them from scratch.

Stop wasting your time arguing with idiots. It's like "debunking" flat earthers.

Just started reading this book for a critical review, thank you for freeing me from the burden of doing so.