Palestine Protestors Won't Explain What They Want But Will Explain Why They Won't Explain What They Want

Gazans are facing real struggles. But the solution is dialogue, not shutting down conversation with those with questions.

I have real questions for the Palestinian protestors who are occupying the center of my university. Questions like: you all keep calling for an intifada—when you say that, does your idea of what an intifada should look like bear any resemblance to the last one which involved terrorist attacks against innocent Israelis? And if not, then isn’t it a bad idea to have your slogan invoke a call for something that last time involved killing a bunch of people? They keep talking about divesting, but they’re never clear on where they want to divest from. General funds? Any company like Microsoft that does business in Israel and make things used in the war effort? Companies like Subway that do business in Israel? Finally, what in the world is the reason to think that having a small number of universities pressure Israel is a good way to stop their war, when in fact the times they’ve been closest to peace have been when they faced the least pressure (e.g. in 2000)?

I’m not unsympathetic to the cause of the Palestinians. I think they’ve been by far the main victims of the conflict, expelled from their homes in 1948 and left to linger in a permanent state of dispossession. I’m additionally concerned about how Israel is carrying out the current war—where they’ve destroyed most of Gazan infrastructure and effectively obliterated Gazan society, all the while killing about 2% of Gaza in just around half a year.

And yet my position in support of the Palestinian cause is much more moderate than is typical at the protests. I support a two-state solution and think that’s the only real path forward. I think that Israel was justified in responding to Hamas’s assault, although one can have serious problems with how they are doing it. But most of all, I think that if one is going to engage in a protest, they should have a reason to think that the protest will accomplish something, rather than being a way college kids can pretend to be significant.

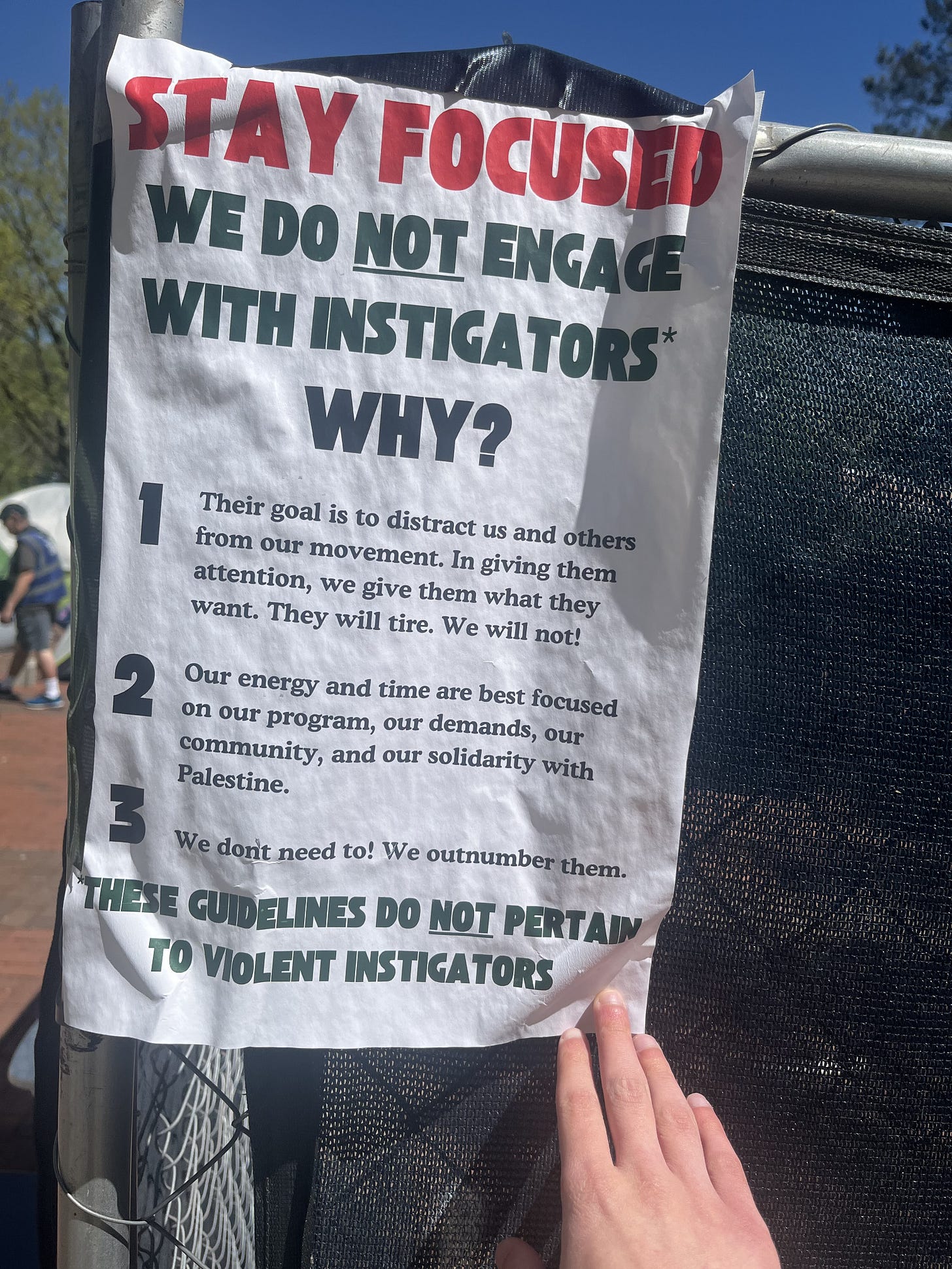

So I decided to go over to the Palestinian protests at my University to talk to the people there. I was genuinely trying to get information about the places they wanted to divest from and the reasons to support their program. When I got there, I was dispirited to find the following sign:

The sign explains three reasons not to talk to those who disagree: first, because those who disagree might distract them from doing other important things like standing about and drinking water, second because their energy and time is better spent on other things like standing about and drinking water (this really feels like double-counting one thing), and third because they don’t have to because there are more protestors than people asking questions.

Now, I can obviously understand why if a person is doing other things like putting up signs, they wouldn’t want to stop to talk to those with questions. But there were various people sitting around doing nothing. There was a desk towards the front where people just went to sit. So why in the world were they so opposed to dialogue? If I was protesting on behalf of factory-farmed animals, for instance, I would obviously stop and talk with people who had questions!

The sign—combined with their prevailing attitudes—represents a crucial vindication of my point in my last article. Because, in their words, they outnumber the Zionists, they don’t have to do the work to persuade anyone that Zionism is a bad idea. Of course, in the real world, outside of their safe space, Israel is overwhelmingly popular among the American electorate, and their support for Intifadas and a Palestinian state from the river to the sea is regarded as crazy.

The claim about not having to persuade people because they outnumber their opponents was particularly galling. As I said in my last article, these people are not moderates. I’ll use the one speech I listened to during the encampment as an example. The speech claimed, among other things, that Bangladesh wasn’t really supporting the Palestinian people because they gave money to the Palestinian Authority who is really Israel’s muppet (who should they give money to—Hamas?) and that some group wasn’t really on board with Palestinian liberation because they supported a two-state solution (by this standard, Noam Chomsky and Norman Finkelstein are too opposed to Palestinian rights). It also referred to Israel the way Iran and Hezbollah do—as the Zionist entity (unrelated, but one of the funnier jokes I’ve told in my life was told in class when the professor mentioned Hezbollah’s opposition to any Israeli state, supported by their claim that they want to eradicate the Zionist entity, in response to which I turned to my friend David and suggested “well, maybe they’re talking about a different Zionist entity”). Positions taken as too extreme for 95% of the American electorate are taken for granted, and yet the protestors have the gall to act as if they outnumber those of a more moderate bent. Obviously, they outnumber moderates in a space that is specifically where people with extreme views gather, but that’s like arguing that communists don’t have to persuade others because the vast majority of people are communists—at meetings for the American communist party.

Fortunately, not everyone got the memo that they don’t talk to those with questions. Early in the day, I went up to the person at the main desk, who was just sitting under a tent. I asked her questions like: which companies do you plan to divest from? She was an older French lady, without any university affiliation. She had no idea. We talked a little bit about the conflict, at which point it became clear that she just didn’t know the main events of the conflict or even know her own side’s talking points.

I can’t really remember how our conversation ended—I think she brought over some people who might know the answer to my questions, at which point they explained that they don’t really answer questions, but I’m not quite positive.

I later returned to the main tables. At this point, it was occupied by a very religious Muslim man. He was my favorite person that I met, having genuine concern and care for the people on both sides and hoping for peace. Unfortunately, we didn’t get very far before a masked activist who wouldn’t tell me his name came up to the Muslim man and explained that the encampment had a policy of not speaking to the uninitiated.

The masked man of an unknown name talked with me, for about a half hour, about why they had a policy of not talking with people who disagreed with them. But he wouldn’t talk about what the encampment aimed to achieve or where they wanted to divest from. If the people organizing it are so busy that they can’t talk to those who disagree, well, why are they spending a long time talking with people about why they won’t dialogue with those who disagree? They seemed to have time to talk about everything except what they actually advocated for!

Eventually, he walked away, and the Muslim man went back to talking about the conflict. He didn’t really seem to care what the student organizers thought—one reason I liked him! That said, he didn’t really have much knowledge of the conflict—he was, for instance, totally unaware of previous peace talks at Camp David and Taba and proposed that Israel’s response to October 7th should have been to pray on it!

A bit later, a kid named Josh who is the most widely known zionist at my university went up and started chatting with the man. This was when some organizers aggressively ferreted away the Muslim man for daring to chat with people on the other side. The man even offered Josh bottles of water and for him to join the encampment! He seemed, unlike the other people there, genuinely interested in reaching out to people on the other side.

The final person I chatted with was a middle-aged communist. She had a shirt saying something about global communist revolution and was representing some communist group. She was the most informed person of the day, yet called for a one-state solution (ah yes, let’s have the two groups that have been violently fighting for a century smushed into one state, especially when one of the groups supports, in large numbers, killing the other group), and claimed Israel was committing a genocide. She also, after talking for perhaps 20 minutes, was told by the student activists not to talk to people like me who had any questions.

I wasn’t being aggressive or combative. In fact, every person I chatted with commented on how friendly and noncombative I was being (I think it’s really, really important to be that way on contentious issues). And the older people actually seemed to care about persuasion. It was the student activists who shut down dialogue repeatedly, who acted like challenging them was a moral affront, who acted like the virtue of their cause was so self-evidently righteous that they don’t have to persuade people to agree with them. After all, they supposedly outnumber the dissenters.

This is a topic on which dialogue is hugely important. The only way to solve the conflict, the only way for both sides to moderate, is if both sides are willing to have conversations with the other. I remember watching a documentary about Israeli and Palestinian children meeting and becoming friends. This made both sides more moderate, more empathetic to the fears and interests of the other sides. Shutting down dialogue is emblematic of a broader unwillingness to recognize the complexity of the conflict, and the fact that both sides have very legitimate grievances.

You can support something moderate like a two-state solution or you can claim to represent the majority but you cannot do both. If you call for the effective eradication of Israel, for a position rejected by ~100% of Israelis and the vast majority of Americans, if you have any sense of how politically untenable your position is, you should be willing to do the hard work of persuading those who disagree with you that you are right. The unwillingness to dialogue represents a peculiar hubris, a failure to recognize that one lives in a bubble, and a clear demonstration that one either doesn’t know or care enough about the conflict to discuss it with those who disagree.

These people do not live in reality or anywhere orthogonally adjacent to reality (only true nerds will get that reference). They live in a joke world where Zionism isn’t mainstream, where failing to cater food to activists illegally blockading a building is failing to provide “basic humanitarian aid.” The student activists are mostly quite uninformed and unwilling to get informed. Because there are supposedly more of them, they see themselves as above persuasion.

The idea seems to be that the time for discussion is over, when in reality it never really started in most cases. The prevailing attitude of the extreme positions can sometimes boil down to: "If you are not 100% with me, I am 1000% against you" which is a recipe for disaster.

They are not there to be right, but join the winning group. Conversely, Reason alone is impotent unlike it becomes socially organized. How to socially organize reason is really “What matters”.

I admire your faith in reason and moral. I hope soon you read about social coordination and game theory. Philosophy is important for everything, sufficient for nothing.