Michael Huemer Is Wrong About AI Hype

The robot overlords are coming

Michael Huemer is one of my favorite philosophers. I’ve read every book, paper, and article he has ever written, and enjoyed them all (this is the sort of statement that sounds hyperbolic but is not). However, even very smart and reasonable people are wrong sometimes (for example, I have, upon occasion, been wrong).1 Huemer recently wrote an article called Is AI Over-Hyped? (his conclusion was yes) which I didn’t think was correct. For this reason, I thought it would be worth explaining my disagreement—to answer the question is “Is AI Over-Hyped?” overhyped?

My general view on AI is that it is overall underhyped, but in particular, people are hyping the wrong stuff.2 There’s lots of discussion of short-term harms like AI plagiarizing art, water use, and electricity use. This stuff is mostly bogus. But there is a real, non-trivial chance of near-term AI that will completely upend the world and bring about economic growth at a speed never seen before in human history. Even if timelines are long, so AI comes in 40 years rather than 5, when it comes, it will probably massively upend the world.

Why do I think transformative AI soon is likely? The basic reason is: if you just project that current trends continue, or even if they slow considerably, AI progress balloons through the moon soon. Does balloon through the moon=doom? Foom? I’m skeptical of those predictions, but you don’t need to assume them for AI to massively upend the world.

The tasks AI can perform consistently have been getting twice as long roughly every seven months. Right now they can do tasks that take hours. With a few more doublings, AI will be able to, at will, effectively replace any human researcher. The number of AI models that can be run has been going up 25x per year. So even if it simply reaches human level and plateaus, it will be as if the population of human researchers is going up 25 times a year.

Or, put more concisely: it’s possible to run more AIs performing longer tasks. If these trends continue, then we’ll have a bunch of AIs that can do long tasks, effectively replacing most human researchers. That will radically change the world. So why does Huemer disagree?

Huemer’s first section expressing skepticism is titled “It Couldn’t Very Well Be Under-Hyped,” where he notes that lots of people have made extreme statements about AI. Yudkowsky and Soares think it will kill everyone, while others think it will usher in global paradise. Because AI predictions have been so dramatic, Huemer thinks that AI can’t be bigger than people are guessing.

Now, it’s basically true that AI couldn’t be under-hyped by the people most hyping it, as some of those people are predicting it destroying the world or causing utopia. But if those predictions are right, then AI is underhyped by most people. Most people are predicting far less dramatic change than imminent doom. Most people aren’t predicting GDP doublings every year. So if GDP doublings are imminent, or AI is going to cause human extinction, then it is currently underhyped. Now, I don’t think that AI will cause extinction, but I wouldn’t be surprised by the GDP roughly doubling in a year, sometime soon, because of AI.

Section 2 of Huemer’s article is titled “the history of hype,” and in it, Huemer suggests that humans have a natural bias towards overhyping things. Lots of people have predicted imminent environmental catastrophe which hasn’t come to fruition. The best explanation, Huemer claims, is that people tend to overhype, and so we should, in general, not believe the hype.

But just noting that some people have overhyped some trends doesn’t prove that humans, in general, have a bias towards overhyping things. Some humans have also mistakenly thought that Mitt Romney would win, but that hardly means there’s a general human bias towards predicting an imminent Romney victory. And there are many examples that point in the other direction. Lots of people underestimated Covid, for example, even when it was pretty clear it was going to take over the world. Similarly, many people underestimated what a transformative impact the internet and social media would have.

Huemer replies to this by saying “great transformations do happen, but they are generally not the ones we expect.” But our evidence for AI being transformative is much better than for other things. Specifically:

It’s already been very transformative. It’s been the fastest growing technology in human history. Predicting some technology that already exists will grow and become more transformative is a lot easier than predicting a brand new technology will be impactful. It wasn’t hard to predict in, say, 2005 that the internet would grow bigger.

There’s in-principle reason to guess it will be transformative because computers that can do almost all of what human brains can do are hugely useful and possible in principle.

One bit of evidence for this is simply: the AI hype people have been right. Back in the 2000s, loads of people were predicting that AI would be a huge deal. Others were saying AI was science fiction. But now it’s a multi-trillion dollar industry.

It might be true that there’s some bias towards overhyping things. But there’s also an opposite status quo bias. People are biased towards thinking things won’t change that much, which is why even when it was clear that Covid would go global, people downplayed it. It isn’t clear which of these effects is stronger, so bias arguments don’t obviously point in either direction.

In my view the best of the bias arguments is that people generally underestimate persistent exponential trends. This was true of Covid, AI progress so far, and solar. It’s also confirmed in lab experiments. Overall then, I think bias arguments weakly point in favor of rapid AI progress.

The other problem with Huemer’s argument: bias arguments have most force when we don’t have very good evidence and we’re just guessing. But in this case, our evidence is pretty good. We have trends, and we can see what happens if those trends continue. So even if one shouldn’t trust the naive intuition that AI progress will be very fast, that’s not an argument against trusting the trend lines.

Huemer then notes that various early AI pioneers vastly overestimated AI progress and cites a bunch of people from around 1950. But these were people making predictions very early on, before we had much evidence. I don’t think that the predictions people made in 1950 provide much evidence for whether AI is being underhyped 75 years later.

Instead, the better evidence is that in recent years, expert forecasters’ timelines for when artificial general intelligence will arrive have persistently gotten much shorter. Metaculus predictions for when AGI would arrive went from 50 years to five years in just a few years. AI progress in recent years has been much faster than was predicted by superforecasters—on some metrics, 50% accuracy has been achieved rather than the 12.7% accuracy predicted a few years ago.

So once again, I think this consideration raised by Huemer backfires. If, rather than just looking at a few hyperbolic statements, we look at how standard predictions have changed more recently, they’ve pointed in the direction of AI coming sooner!

Huemer next describes that even though AI so far has been useful, it hasn’t been radically transformative. He writes:

You might say: “Give it time!” But the AI boosters have been predicting amazing transformations to happen really quickly. Based on what people were saying when Chat GPT appeared in 2022, shouldn’t I expect my life to be transformed by now?

We have had progress really quickly. Quoting from Preparing for the Intelligence Explosion “GPT-4 performed marginally better than random guessing. 18 months later, the best reasoning models outperform PhD-level experts.” That’s pretty quick progress. Sure, it might not be as quick as a Yudkowsky-style FOOM, which I agree there’s increasing evidence against, but it’s not evidence for progress being slow. Progress has been amazingly fast.

Huemer is skeptical that the models we have could be that useful even if capabilities improve. But if capabilities improve, the models could accomplish basically all research tasks a human could. They already can code well and write decently long reports decently well. Once the AI can do this better, it will be as if we have an unimaginably large population of researchers. That would hugely transform the world—especially because, once we have loads of researchers, they can figure out ways to operationalize other research and to advance AI capabilities. They could run simulations and make robotic advancements that allow the other research to be used.

Huemer’s final argument is that the AI can’t make important breakthroughs because all it is doing is predicting sequences of text. He denies that this is true understanding. But even if it’s just mimicry of true understanding, it can still be useful. Even if the AI is just like the person in Searle’s Chinese room, one can make all sorts of breakthroughs by understanding sufficiently advanced patterns.

Already AI can code, write, and give original takes on new arguments. If you give it an argument no one has ever made before, it can analyze it sensibly. So whatever it’s doing, whether or not it counts as true understanding, I don’t see why it can’t be used to make breakthroughs.

Maybe you’ll deny that this is understanding in some deep philosophical sense. But in any case, it runs according to a complex algorithm that functions as if it understands things. That’s how it can do all the cool stuff it does. But an abstract algorithm that can mirror true understanding can, even if it lacks true understanding, change the world.

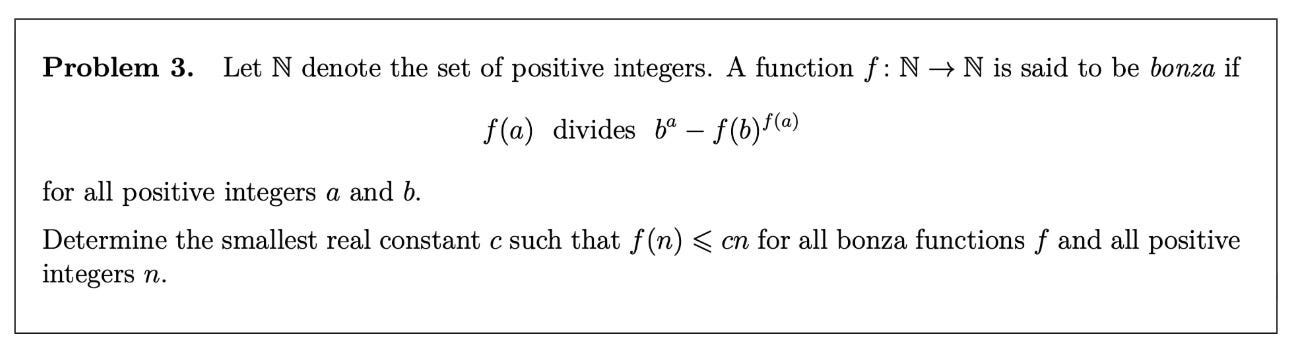

Regarding the claim that the AI is just predicting text, Steven Adler has a very nice piece about why this is misleading. First of all, the AI is able to solve advanced math problems that it hasn’t seen before, like the one shown below.

If this is just predicting text, it’s certainly a very different enterprise from guessing the next word in a story. It shows that the capabilities one gains in trying to predict text are fairly advanced. If so, they could be dangerous.

Second, what the AI is doing isn’t even well-described as predicting the next word. It’s originally trained on lots of text, but then gets exposed to reinforcement learning. It executes a layer of thinking before typing out any text to you. In addition, given human feedback, the AI is now optimizing not for predicting the next word but for giving an answer that satisfies humans. This is very different from simply predicting the next word—its aim is to find genuinely good answers to questions users ask.

One useful analogy is humans and reproduction. We evolved to reproduce. But it turned out that the best way to do that was to gain all sorts of advanced reasoning capabilities. Analogously, the AI is built to predict text. But to do that, it needs to understand the world. You need to understand the world to accurately predict text about the world. And it’s been able to.

The AI isn’t just following a simple, rote algorithm. It can, for example, understand subtle jokes, solve Winnograd schemas, give new philosophical arguments, and provide original insights. So either the AI is actually reasoning or it’s doing something enough like reasoning that it could be hugely useful.

Huemer doesn’t think the AI would be conscious. I somewhat disagree about this, but I don’t think it matters. Even if the AI isn’t conscious, it can still perform the kinds of computations it currently does but at a much higher level. If those capabilities advance to an arbitrarily great degree, it could be hugely transformative. This is the reason investors have generally not heeded Huemer’s skeptical advice, and instead poured trillions of dollars into building transformative AI.

A lot of Huemer’s arguments are “outside-view” arguments. They don’t look as much about recent AI capabilities, instead relying on general heuristics that apply to lots of things (e.g. “don’t believe the hype.”) A lot of the heuristics Huemer applies are pretty useful in other domains. But our evidence about AI capabilities is sufficiently good and specific that one should analyze specific arguments instead of broad, high-level heuristics. Most things on Earth won’t blow you up, but this is not a strong argument for standing on a land mine.

Proof for skeptical readers: if I had never been wrong then my statement that I’ve been wrong would be wrong.

Neither overhyped nor underhyped but a secret third thing.

“So I’m not predicting that there won’t be any major transformations of our society in the next 50 years. I’m predicting that whatever they are, they won’t be what we’re expecting. Maybe AI will have big effects, but different ones from the ones people are anticipating. Or maybe some other technologies will appear that will prove much more important.”

Huemer explicitly says he’s not predicting there won’t be major transformations. Just that the transformations won’t be what people are expecting. I assume he’s referring to the hyped predictions, even if that is misplaced hype. I still think that’s right.

I agree with Nathan Witkin, I don't understand those claims about the tasks doubling. I am a software developer and I recently worked with a vibecoded (largely or entirely AI generated) codebase, and it really was quite messy and subpar, even if it technically worked, kinda like if it had been a rush job or throwaway project. Over on hacker news I actually saw someone argue that now it no longer matters if code is maintainable, just let the AI do it, which seems very stupid, it wouldn't be good to have code that is incomprehensible to humans do important things. And Claude Opus 4.5's abysmal performance at playing Pokemon Red (it's looking like it will never beat it) seems like a much better benchmark for general reasoning capability than the actual benchmarks.

However, I do use AI, and I suspect the trajectory for AI will be much like the internet, there's a bubble, and a bust, but it keeps growing past the bust. Strongly suspect LLMs will not get to AGI or ASI, a paradigm shift or two will be needed.