“Doubt thou the stars are fire;

Doubt that the sun doth move;

Doubt truth to be a liar;

But never doubt I love.”

—Hamlet

There are lots of ways we could be in sceptical scenarios. Fortunately, we’re not in a sceptical scenario. Alexander Pruss uses this to make an interesting argument for God. I think his argument is pretty good, so here I’ll explain the argument.

Notably, the argument is not about how we come to know that we’re not in a sceptical scenario. That might be primitive or something we can leave to the epistemologists. To give an analogy, I know that I exist. Theism doesn’t explain how I know that, but it might explain why I do exist. There are lots of sceptical scenarios that aren’t totally obviously false. Pruss lists some:

Demons deceive most of us about most things.

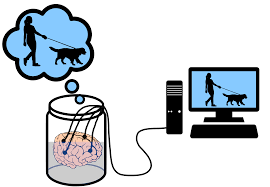

We are ignorant brains in vats.

We ignorantly exist in a computer simulation.

Ignorantly simulated people vastly outnumber organic ones.

We are ignorant Boltzmann brains.

Ignorant Boltzmann brains vastly outnumber normal ones.

We are disembodied souls having illusions of embodiment.

We evolved with little connection between truth and survival value in morality.

The probability of objects popping into existence ex nihilo is high or undefined.

The universe came into existence fully-formed five minutes ago.

Everybody else is a zombie.

There is no correlation between mathematical beauty and physical truth.

Here are five more that I thought of:

Simplicity is not a virtue of infinite value.

Something like modal realism is true.

Small simulations.

We’re in a very vivid dream.

Evolution has made our perception really inaccurate.

And many of these aren’t super obviously wrong. One of my smartest friends thinks that there’s a plausible argument, along the lines made by Donald Hoffman, that evolution would be likely to make our perception very unreliable. I haven’t looked into this that carefully, and I’m sceptical of it, but it could be correct.

Similarly, it’s not totally obvious why simplicity is a virtue. Philosophers have largely had to take it as primitive. Yet even if it is a virtue, given that there are uncountably infinite ways induction could break one second from now (e.g. the world being replaced by any subset of pieces of wood with lengths of any of the natural numbers), for induction to be right simplicity must be of effectively infinite value. Shwitzgebel has defended the plausibility of a few sceptical scenarios. The Boltzmann brain one is, I think, the most troubling—models of physical reality that aren’t finely tuned for low entropy produce the result that most people like us will be Boltzmann brains. But the vast majority of possible models of physical reality don’t have low entropy.

Theism has a natural account of why all these sceptical scenarios are false. It’s bad to be in a sceptical scenario. That’s not a harm that God would impose on people. So therefore theism explains them all in one fell swoop.

This is a better explanation because it’s less piecemeal. Given that there are 17 possible sceptical scenarios listed, even if each of them has a merely 5% chance of obtaining on atheism, the odds that none of them would obtain is just over 40%. If each of them has a 10% of obtaining, the odds none would obtain would be just over 16%. So one must be really confident in their solution to sceptical scenarios for this not to provide significant evidence for theism.

I also think there might be a successful argument from our knowledge that we’re not in sceptical scenarios, though that’s not the argument that Pruss makes. The argument would be as follows:

If atheism is true, the odds that someone with my experiences would be in a sceptical scenario is pretty high.

The odds that someone with my experiences would be in a sceptical scenario is not pretty high

So atheism is false.

You might reject 1 on the grounds that one has basic justified belief that they’re not in a sceptical scenario. But I’m sceptical of this. If you posit some fundamental model of reality in which most people like you are Boltzmann brains, then you it’s illicit to posit that you’re not a Boltzmann brain brutely. Rather, you should posit a model of reality where most people like you are not in sceptical scenarios. But theism is the best explanation of that.

I’m less confident about the argument that atheism implies scepticism than I am about the abductive argument, though. It’s also interestingly analogous to the argument from moral knowledge, where there’s both an abductive version about how we come to have certain types of knowledge and an epistemic question about whether atheism undermines our justification for certain beliefs.

I think my hesitations here are:

1) Given what God already tolerates (on non-skeptical scenarios), and given plausible theodicies about why She does so, is the harm of being in a skeptical scenario something we have high prior probability She would protect us from? If anything theodicy (by your account the strongest line against theism) looks much *easier* within a skeptical scenario.

2) This might be tussling with the premise that skepticism is false, but I feel like there is a case to be made that eg “perhaps I am most likely a Boltzmann brain, but my actions only matter if I am not, therefore I will act on the premise that my actions have consequences.” One can regard this as a Kantian rather than dogmatic (neutral valence of dogmatic) solution.

What do you make of the Hindu notion of maya, isn't that a theistic skeptical scenario (there is a supreme God in Hinduism, even if there are lesser ones as well)? You may even have called it out when you posited reality as collective dream in a skeptical scenario. There doesn't seem to be anything bad about being in a collective dream, it just is what it is.