A Core Area of Disagreement Between Theists and Atheists: Is Theism Ridiculous?

Is believing in God like believing in Santa Claus?

There are many disagreements between theists and atheists. They differ, of course, in their assessments of whether various arguments for God’s existence are successful. But in my view, the biggest difference between the two is in terms of their broader approach to the question. Specifically, the most significant area of disagreement concerns whether God’s existence is ridiculous.

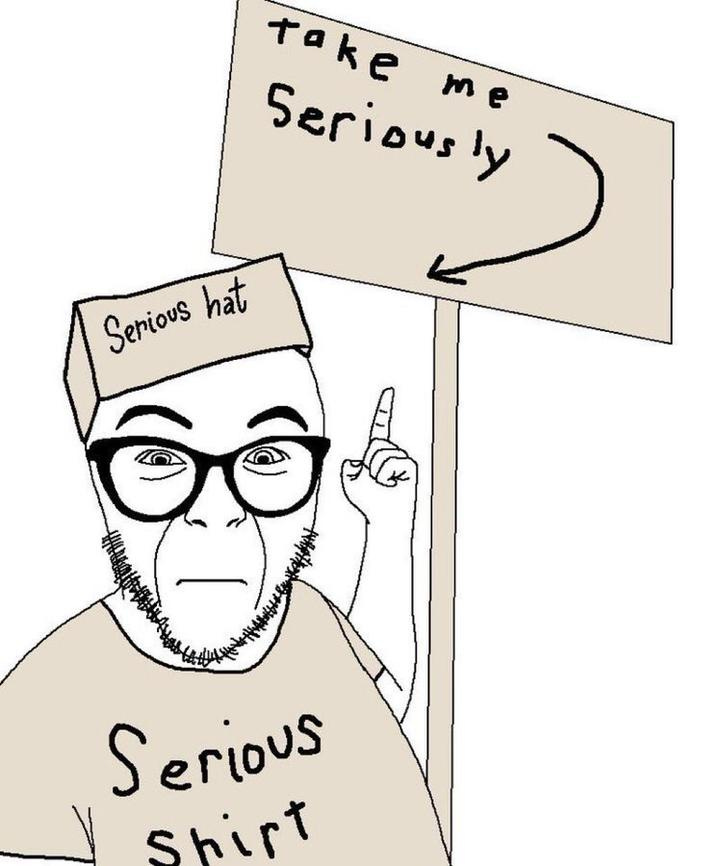

I think a lot of atheists see belief in God as like belief in Santa Claus or the Easter Bunny. In some cases, this is because of a specific argument—perhaps, like me when I was an atheist, they think the problem of evil disqualifies theism from being a serious hypothesis, just as Jeffrey Dahmer’s murderous cannibalism disqualifies the “Jeffrey Dahmer was a great guy” hypothesis. Perhaps it’s a more general sense that belief in God is belief in some extraordinary, outrageous, magical hypothesis.

If someone has this view, then they probably won’t be swayed by the Bayesian arguments for theism. They’ll see those as like Bayesian arguments for Santa Claus. I mean, sure, the odds of kids all around the world being delivered presents is vastly higher given the Santa Claus hypothesis than given its falsity, but no one takes that seriously as an argument, because the conclusion is ridiculous. We would all laugh at a comprehensive, cumulative, abductive argument for the Easter Bunny. If you think theism is ridiculous, then you can always answer any argument for theism by invoking some ad hoc theory.

The most significant shift in my views on the topic of God’s existence came when I changed my mind about whether theism was totally ridiculous. This—more than considering any one argument—was responsible for the biggest shift in how I viewed the topic. In light of this, I think the subject deserves more careful evaluation. We should, rather than tacitly assuming that we’re right about the ridiculousness question, argue it out.

So who is right? Is theism ridiculous?

Unsurprisingly, I think the answer is no (I am a theist after all, and people rarely think their own view is ridiculous). I think theism and atheism are two radically different worldviews about the ultimate foundation of reality, and they don’t start with astronomically different priors.

A first general consideration: if most people who have ever lived, including some of the smartest people ever, believe some view, then you shouldn’t start out assuming the view is ridiculous. Maybe it’s wrong, but you should at least take the view seriously. While Von Neumann was a Catholic on his death bed, he never believed in Santa Claus. This is one important reason to be distrustful of the intuition that theism is ridiculous; if very smart people believe something, you should have a high bar for declaring it completely absurd. And very smart people are theists.

Now, there are some people who are both smart and crazy—for example, some conspiracy theorists. But a great many theists are smart and not crazy. If one takes the time to read C.S. Lewis, for example, they will find someone brimming with both extreme cleverness and wisdom. There are smart God-believing physicists, philosophers, mathematicians, and more. It is unlikely you have some unique insight that all of history’s God-believing geniuses lack that makes clear the core theistic absurdity.

This is not to say you should automatically believe theism just because smart people think it’s true. It is only to say that if you end up extremely confident that a view is wrong—despite it being quite widely held among brilliant people—you had better have a strong reason for doing that. You should not think it absurd at the outset of inquiry. You should at least take the view seriously.

Here is one other related consideration: the philosophy of peer disagreement seems to indicate that if there are other very clever people who disagree with you, then you should not be extremely confident that you are right and they are wrong. Perhaps they see things you do not. Nothing much licenses the very confident belief that you are right and they are wrong when you are no cleverer than them.

Suppose we take that seriously. Well then, prior to considering the specific evidence, you should think theism might be absurd and might not be. Let’s say you start out thinking there’s a 90% chance it’s absurd and a 10% chance it isn’t. For simplicity, assume that if theism isn’t absurd, it has a 10% chance of being true—prior to considering the evidence—while if it is absurd, it has a 0% chance of being true. This would still mean that your overall prior in theism, in light of your uncertainty, is 1%. In short, then, if you are not sure if a view is absurd, then you should treat its plausibility as less than you would if you were firmly convinced it was not absurd, but not as if it is absurd. A 10% prior probability of having a 10% prior probability on the best theory of priors is still a 1% prior.

These are some general reasons for caution concerning theistic absurdity. So now let us see: is theism absurd like the other views are?

I think it is not. Why are the other views absurd? Well, they posit something very specific and complex, supported by no serious evidence and opposed by quite a lot of evidence.

For instance, take belief in Santa Claus. A fat, jolly, North-Pole dwelling, elf-employing, red-coated fellow who delivers presents around the world is a very specific thing for one to suppose exists. One should have a general presumption against thinking some very specific thing dwells in our world, for only a small portion of possible things dwell in our world. If the thing is very different from that which we experience, we should be even more skeptical.

In addition, there is strong contrary evidence. If there was a man delivering presents to everyone in the world, we should expect a great many parents to wake up with wholly unexplained presents appearing for their children. This is, of course, not what we observe. We should additionally expect many people to spot Mr. Claus, and parents shouldn’t notice a robust correlation between the toys they buy and the ones supposedly delivered by Santa Claus.

Now, is God like this?

No! God is not arbitrary and constricted in the ways Santa Claus is. He is wholly limitless—a mind totally without limits. If you are a theist, you can write out fundamental reality in one sentence: there is a mind without limits.

If an entity is simply the limitless instantiation of something that is very plausibly fundamental, then that does not start out with the same kind of absurdly low prior as if it has random limits. The theory that the universe is exactly 3290432732 meters across has a very low prior—the theory that the universe is infinite does not. Infinity is not arbitrary. Fundamental things, extrapolated to infinity, does not have the same arbitrariness and complexity of a random mix of flesh, tissue, and magic like Santa Claus.

If physicists could explain the universe very well by supposing that one of the things in the physical world was simply instantiated to an infinite degree, they’d have found an excellent physical theory. Doing the same for mind—for one of the three fundamental kinds of things—similarly merits a pretty high prior probability. So while theism is very specific, it pays for its specificity in simplicity. The theory that the laws of the universe are the same everywhere is also specific. There are infinity ways for it to be false and only one way for it to be true. Nonetheless, we are rational to believe that theory.

Now, is God like Santa Claus in that his existence is wildly contradicted by the facts of the world? My answer here will, of course, be controversial, but I think quite the opposite. God explains a great many disparate, surprising facts about the world. The theist has just one great mystery—evil. The atheist has dozens.

There is no strong cumulative case for Santa Claus or the Easter Bunny. There is for God.

Now, I want to caution against one common claim of similarity between God and the Easter Bunny: one might suppose that the absurdity in believing in Santa Claus or the Easter Bunny comes from the fact that they’re very different from the things in our experience. This argument goes: you should have a high bar for believing in something extraordinary, and something very different from the stuff in our experience is, by definition, extraordinary.

But this argument is wrong. There are many things that are unlike the stuff we see but aren’t absurd. Dark matter is very unlike the matter we see. Atoms are very much unlike what we can see with our eyes at the macro scale (for instance, they are smaller). Nonetheless, neither are extraordinary claims, worth dismissing and ridiculing.

Any view of ultimate reality will have to posit something rather unlike the things we observe. Whatever it is that gave rise to the universe is unlike the universe. If the atheist posits that there is some unexplained and uncaused matter, then they believe in something very unlike what we experience—for all the matter in our experience is caused and explained. There is no reason to expect whatever is fundamental and explains the rest of reality will be like the stuff we observe. In fact, it would be quite shocking if it was.

Now, if something is very different from the stuff we think exists, then you shouldn’t automatically believe in it. You’ll need evidence to believe in a new kind of thing. But theists claim that we do have evidence—quite a lot of it, in fact. Maybe theists are wrong about this. Maybe the arguments aren’t any good. But, at the very least, one can’t use theism’s absurdity to dismiss the success of theistic arguments, if the alleged failure of theistic arguments is the explanation of theism’s absurdity.

One common justification atheists give for theism being absurd is that the problem of evil renders theism very improbable. To quote an analogy from Ben Burgis, believing in theism is like believing in a giant who paints the sky yellow every morning. Not only is there no convincing evidence for such a being, it contradicts the facts. The sky isn’t yellow!

I will join these people in admitting that the problem of evil is a strong argument against theism. It lowers the odds of God by a lot. But sometimes, it is worth believing something even if there are strong arguments on the other side. Once we have admitted that evil is powerful evidence against theism, the only remaining question is whether it is a knockdown blow—a K.O. or just one consideration among many.

I think there are several reasons to reject the idea that the problem of evil is an argument so powerful it cannot be beaten by contrary arguments. Certainly most arguments are not this powerful. In order to think the problem of evil singlehandedly demolishes the possibility of a plausible theistic view, one would have to be very confident that the argument works. This would be one of the few cases in the history of philosophy where a position was proven—almost beyond doubt—by a single argument.

But what merits such confidence in this position? Certainly God, if he exists, knows a great many things that I do not. In fact, the gulf between what God knows and what you know far surpasses the gulf between what a child knows about the universe and what Ed Witten does. Just as a child should not declare with extreme confidence that adults have no good reason for some otherwise puzzling actions, we should not be confident in the same with God.

It is not merely that God knows of goods and evils that we do not. He also knows the future. He knows how things will play out every year throughout eternity. In light of this, he will inevitably be aware of a range of reasons that we are not. We should not be surprised, therefore, that he permits certain things that appear to us to be evil.

In addition, there are a lot of theodicies. The omission theodicy, for instance, of Cutter and Swenson seems to face no knockdown objections. Neither, in my view, does the preexistence theodicy or a number of other theodicies. Very clever people, over the years, have thought of many theodicies, some of almost unfathomable complexity. You—who presumably haven’t read even 1% of what is written on the subject—should not be 99.999% confident that they all fail. You should, in other words, think there is some not unreasonable possibility that God, if he exists, has a good reason for allowing evil.

In light of these considerations, there aren’t strong grounds for thinking theism is absurd. But once one recognizes that it isn’t absurd, they have to compare the theories. They must see, in other words, whether it explains the world better than atheism. In my view, as I’ve argued at length, it does. If theism is not absurd, then atheism’s probability collapses under the cumulative weight of all the arguments—all the things, in other words, that God explains better than a Godless world. If God isn’t absurd, then he is very likely real.

I actually think this misunderstands most atheists quite a bit (at least the reasonable ones).

Here is something that most reasonable atheists DON'T claim, in my experience:

- There is no chance there is some creator of the universe we live in

- The fact there is 'evil' in the world disproves there is a god

- Believing in a god/creator is the same as believing in Santa Claus

Here is something most atheists do claim:

- Without more evidence, there is no reason to believe in an omnipotent god that intercedes in human life, and it is irrational to have such a belief

- Without more evidence, there is no reason to believe in an afterlife, and it is irrational to have such a belief

- Certainly, no religion on Earth has this shit figured out, and a lot of specific religious beliefs are indeed no different than believing in Santa Claus

There is a lot of Motte and Bailey going on when many 'theists' discuss the topics above. If someone wants to argue that they think it's more than likely that there is a creator of the universe, cool. I actually don't think most atheists give a single shit about that. However, that's not generally what believers are arguing, and certainly not at first.

Atheists saying theism is ridiculous and that all smart religious people are just doing whishfull thinking is the same as christians and muslims saying that all atheists know God exists deep down but they just want to sin.