Don't Vote For Republicans Because Democrats Are Annoying!

If you find yourself adopting an ideology because some people were annoying, you have been brain hacked by random strangers

If you ask lots of people why they became conservatives, a non-trivial portion of them will explain that their journey to conservatism had a lot to do with an annoying left-winger. Perhaps some iced-latte drinking, blue-haired liberal they/them said that using the phrase “master bedroom” makes a person literally Hitler, and this negatively polarized them into loving Trump. When you hear stories about why people left the left, a lot more of them have to do with left-wingers being annoying or vile in some way than any sort of policy.

This is very silly!

When you vote for political candidates, you’re not joining a social club with everyone else who voted for them. Even if it turns out that people of some political ideology are more annoying than people of other political ideologies, that would have nothing to do with the correctness of the political ideology, except perhaps as a weak and indirect signal. Liberals being annoying doesn’t mean liberal policy is bad.

One’s political views should be influenced by which party adopts superior policies. That is, after all, what one elects representatives to do. You’re not picking a friend. You’re not picking someone to get a beer with. That lots of people treat the fact that you could find a candidate relatable while getting a beer as a major point in their favor shows something quite tragic about Democracy—that often voters vote in completely idiotic and nonsensical ways.

Imagine a person told you that they switched political parties because they felt a positive emotional reaction towards Republicans, having nothing to do with their politics. We’d all regard that as irrational and with disdain. We should look down on those who make monumental decisions, when others’ lives are on the line, in ways that are knowingly totally non-rational. It would be like a Doctor who made a decision about which treatment to give you based on which treatment they had a more positive emotional reaction towards. It should never ever happen.

But making political decisions based on which side is more annoying is exactly the same. It too involves making decisions based purely on emotion, without any consideration of costs and benefits. It too should be treated with disdain. Important decisions deserve careful thought.

(in an excellent article that was the inspiration for this post) put it very well:It’s become too common to hear people talk with pride about how they got negatively polarized into believing something.

“The left went crazy and drove me to the far right!”

“I used to be a normal liberal but other liberals were so annoying that I’m a communist now!”

This is mental weakness.

It's embarrassing to let people negatively polarize you. You're an adult. Stop it. Negative polarization means your brain got hacked by individual annoying strangers. That’s ridiculous.

When I hear someone say "I once met a very annoying person who believed X and now I hate X as a result" my only thought is that the world has 8 billion individuals in it, each one an infinite story we can just barely begin to understand in our brief time here. This person I’m talking to has let that precious truth slip from their field of vision.

You should not allow your brain to get hacked by random annoying strangers!

It’s bad enough to let your brain get hacked by non-rational arguments from strangers. But if your views have changed dramatically because some random person that you don’t like has that view, something has gone badly wrong! You have abandoned reason, in some deep sense. You have become less like an agent and more like a set of conditioned reflexes—lashing out at whichever side annoyed you most recently.

It also makes your political views wildly contingent. It means that if you hadn’t met the same people, even if you’d been presented all the same information, you’d have totally different political views. It means that someone could change your views just by hiring an annoying person to espouse political views next to you. If someone could change your political ideology by hiring someone to go “aggravate, aggravate, aggravate, I support PEPFAR, aggravate, aggravate,” then you should seriously reconsider your life choices. As Masley says, this is mental weakness. The facts don’t care about your feelings.

(The same, of course, goes for Democrats. You shouldn’t be a Democrat because you find Republicans unpleasant, though I think this phenomenon is a lot more common among right-wingers than left-wingers).

That said, this is how a lot of people reason. One of the reasons there has been a rightward shift is the perception that left-wingers are screechy and preachy and annoying. It’s completely ridiculous that people make decisions about politics based on which side is more annoying, but unfortunately, they do.

For this reason—and others—you should strive not to be annoying. In political messaging, you should try to avoid saying things that make you sound insane. You should not become unhinged over Sydney Sweeney jeans ads. You should not have random meltdowns over nothingburgers.

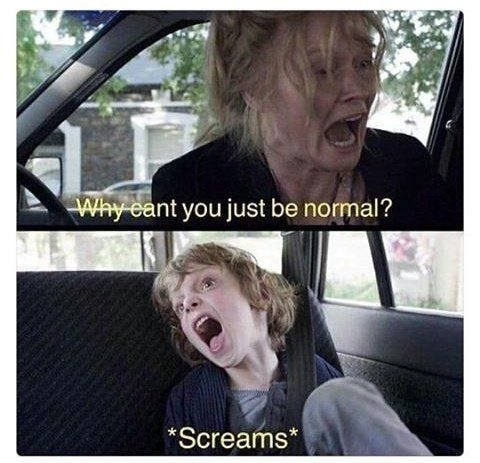

Some of the people who have most increased right-wing support have been unhinged left-wingers melting down (often while being odd-looking). You still see memes about random people in 2016 who had unhinged reactions to right-wing figures. Conservatives sometimes get so desperate for unhinged liberals acting crazy that they pretend liberals are melting down even when none are. It is sad that this influences anyone’s political views, but most people aren’t that moved by rational argument. If you act crazy, your side will lose political support. So don’t act crazy.

I see this with a lot of vegans. Sometimes vegans will comment on random social media posts where people eat meat, and tell them that they are paying for rape and murder. Now, as it happens, I agree that eating meat involves paying for rape and murder. But I think this is not a good strategy for persuasion. By having over-the-top dramatic reactions to people eating food, you are unlikely to persuade anyone, and may very well turn people off. You should make your case forcefully and respectfully—communicate the extreme wrongness of meat-eating, but ideally do it in contexts where it’s socially appropriate and where you don’t sound insane.

On the other hand, people who say that they aren’t vegan because vegans are annoying are whiny babies. Vegans aren’t just people who personally don’t like meat-eating—we think it’s morally wrong. We make arguments, like that you shouldn’t cause others egregious suffering for trivial reasons and that eating meat does that. Now, perhaps vegans are wrong. But if you find yourself acting in a way that might be egregiously evil because some people who opposed the act behaved hysterically, you are not a serious person.

It is both true that you shouldn’t do annoying vegan evangelization because it will turn people off to veganism and that the people turned off to veganism because some vegans were annoying are whiny babies. Unfortunately, you have to sometimes make concessions for people’s defects (ie, being a whiny baby).

I advise you thusly: don’t act in a way that appears unhinged, and don’t allow other people acting in a way that appears unhinged to influence your views.

With veganism I don't think people are getting "negatively polarized" - most people eat meat to begin with, and don't want to give up their meat-eating, so they're predisposed to dismiss vegetarians/vegans and fixate on the annoying ones as a justification for not doing what they already didn't want to do in the first place. And I suspect something similar is happening politically, though perhaps to a different degree.

Good take! But here are some objections to consider:

(1) That those who believe p are unlikeable can be evidence against p, given that those who believe p are unlikeable in relevant ways. If they're unlikeable because they melt down the moment their political views are challenged, for example, that constitutes evidence that their political views haven't been refined through thoughtful argumentation. And political views that haven't been refined through thoughtful argumentation tend to be false. So, it might be rational to doubt a political ideology once you realize that most of the people you know of who hold it are prone to hysterical meltdowns. (I'm not granting that leftists are more prone than others to hysterical meltdowns, by the way -- this is an empirical question that can't be resolved by surveying non-randomly sampled social media posts.)

(2) It's possible to acquire evidence for an ideology as a (causal) consequence of spending more time with people who hold that ideology. It may be that those who are driven rightward by leftist misbehavior undergo the following, two-step process: first, they stop associating with leftists and start associating with conservatives because they find the latter less annoying than the former; second, as a result of associating with conservatives, they encounter arguments for conservative policies they haven't heard before (or objections to liberal policies they haven't heard before) and shift rightward ideologically in response to those arguments.

(3) You assume that rank-and-file voters should choose how to vote based on which policies are most likely to work. But a growing number of applied political philosophers deny this. According to them, the probability that your vote will change the outcome of a democratic election is so tiny that it's foolish to vote for the sake of changing the outcome. If you're rational, you'll instead vote for social reasons -- e.g., reinforcing your relationships with those close to you. If partisanship is really just a vehicle for strengthening social bonds, then it might be rational to vote for the party whose members you personally like better. (I hate this view, but it's not easy to articulate what's wrong with it.)

To clarify, I substantially agree with the content of your post. But considerations like (1)-(3) have given me food for thought recently.