(I started a brief wordpress blog that will mostly be for me to record things I’m thinking about. It won’t be edited at all and is mostly for my sake so I can remember old arguments, but if anyone wants to read it, here it is. First article is about why double-halfing in sleeping beauty and related cases is silly).

I, like a sizeable portion of philosophers (about a third), think that consciousness is non-physical. This position is adopted by many thoroughly reductionist, atheist philosophers, and I adopted it during the deepest throes of my atheism. David Chalmers, Saul Kripke, and Derek Parfit, three of the most impressive philosophers of the last century—two of whom are/were confident atheists—were well-known for adopting it. I want to make it clear: people don’t adopt non-physicalism exclusively—or even primarily—because of religious presuppositions, and numerous people like Chalmers who feel ideologically drawn towards physicalism end up abandoning it because it cannot explain consciousness.

Non-physicalists claim that consciousness is not physical, in the sense that the mere behavior of physical stuff isn’t enough to generate consciousness. Arrange atoms the right way and you can get them forming all sorts of things—chairs, tables, and so on. Non-physicalists claim that physical processes alone will never get consciousness. Physics only describes how things behave, yet consciousness is not about how things behaves, but what it’s like to be in a certain state.

Non-physicalists claim that consciousness comes from certain fundamental psychophysical laws. There are fundamental physics laws that say that when some physical state is present another one arises; for example, gravity says when stuff has mass it pulls in other stuff with mass (gross oversimplification obviously). Non-physicalists claim there are psychophysical laws too that say that when certain physical states arise, it gives rise to conscious states. Just as there are a whole range of fundamental physical properties—mass, spin, charge—non-physicalists of the popular variety claim there are also non-physical properties. Others claim that consciousness is affected by matter but is it’s own separate thing. The core claim non—physicalists make is that physical stuff isn’t enough on its own to get consciousness: physical stuff gets you increasingly complex structures but never there being something it’s like to be in a physical state.

One of the most common arguments against physicalism is called the knowledge argument. When you present it to physicalists on the street (note, this is contrasting them with physicalists in the academy, rather than physicalists in the sheets) they usually vomit up a medley of confused objections that amount to reiterating their position rather than addressing where the argument goes wrong. But I think the argument is an extremely powerful consideration against physicalism, and in this article, I’ll explain why.

To use a famous example from Frank Jackson—who tragically joined the dark side and joined the legion of physicalists—imagine a neuroscientist named Mary. Mary is the world’s greatest neuroscientist. Mary often has Good Will Hunting-esque feats of brilliance, where all the other neuroscientists complain “she is so much smarter than us, and better at neuroscience than we are—it’s making us upset.” Mary knows everything there is to know about the neuroscience of the brain.

Unfortunately, Mary is trapped in a black and white room (no one cares about pure philosophy divorced from politics, so imagine, depending on your views, that she was placed here either by an illegal migrant let in my the Biden Harris administration or by the Trump administration persecuting their political enemies). She has never seen anything red. It seems like no matter how much neuroscience Mary learns, she’d never learn what it’s like to see red. Thus, we can argue:

Mary in her black and white room can, merely by reading textbooks, learn everything physical.

Mary in her black and white room cannot, merely by reading textbooks, learn everything about consciousness (she cannot learn what red looks like).

Therefore, some things about consciousness are non-physicali.

I think 1 is on extremely firm footing, and it’s very widely accepted. Mary could learn every fact about chemistry, biology, physics, and so on simply by reading the textbooks. Physical facts can be exhaustively described in terms of physics and in terms of behavior—they’re the sorts of facts that you can learn about just from a textbook. If Mary could learn every other physical fact just by reading from textbooks, why couldn’t she learn this one?

Here’s another way to see this: on physicalism, consciousness is the same thing as a particular physical system. But if A and B are the same thing, and you know that, and you know all the facts about A, then you also inevitably know all the facts about B. If you know all the facts about water, and you know it’s H2O, then you know all the facts about H2O. Thus, if Mary can learn all the facts about brains, and brain states are the same as mental states, then she can learn all the facts about consciousness.

INTERLUDE: A VERY SHORT PLAY IN THREE ACTS

ACT 1: I had a housemate last year named Mary. She had a room. It was Mary’s room.

ACT 2: I made this joke exactly 1 billion times and it remained funny each time.

ACT 3: Her room, unfortunately, had red in it. She was also not the world’s greatest neuroscientist :(.

END THE INTERLUDE

When you present this argument to normal physicalists, you almost never get anyone. I have, on at least 1 billion occasions, at various Rationalist meet-ups given the argument, only for my interlocutor to flail around soliloquizing rather than clearly enumerate a premise they reject. The most common thing they say is roughly the following:

Of course Mary wouldn’t see red in the room. Ever heard of neuroscience? A person can only see red if their brain is in certain states. Just reading textbooks about how people see red doesn’t put you in the brain state of seeing red, so therefore, Mary could never see red.

(Sean Carroll, a very smart guy who should know better, continues making this error to this very day).

Everything in the above paragraph is correct. Physicalism doesn’t entail that Mary would ever see red while in the room. It implies something much stranger: that Mary, while in the room, would be able to learn what it’s like to see red.

None of the premises of the argument are about whether Mary would experience red, they’re about whether she’d know what it’s like to see red. But this sort of knowledge of physical facts can be had in a dark room. To learn all the facts about astronomy, you don’t need to venture out into the world—you can, in theory, learn them all from textbooks. If consciousness-facts are the same, why is consciousness any different? This is why, if you look carefully, such a claim doesn’t disagree with any particular premise.

Physicalists, therefore, tend to deny premise 2, though they often do it while claiming that Mary does something sort of like learning a new thing. David Lewis, for instance, claims that when Mary exits the room, she doesn’t learn some new fact, but she learns a new skill. When you learn to play the violin, you’re learning a new skill, but you don’t become aware of new facts that you were previously ignorant of. Others claim that Mary doesn’t learn anything new but becomes acquainted with red. If a person saw Oxford after reading about it repeatedly, they’d come to know Oxford in the sense that they’d experienced it, but they wouldn’t become aware of a new fact. After meeting Trump, you’d know Trump, but you wouldn’t have learned anything new.

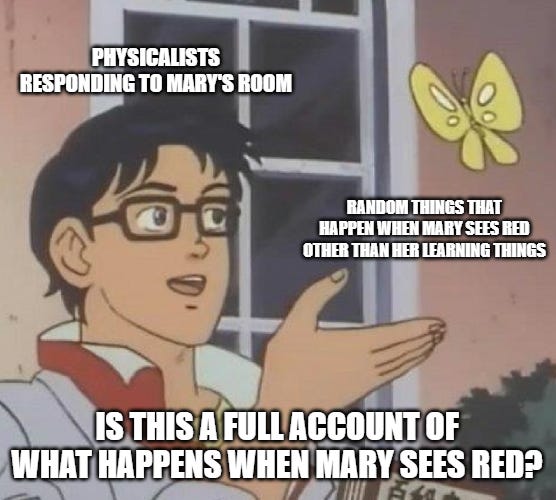

I think the problem with these views is well summarized by the following meme:

Yes Mary gains a new skill—she’s now able to sort oranges from apples more easily. Yes Mary is acquainted with a new fact. But it seems that on top of that, she learns something new. She can say to herself “so that’s what red looks like—I was wondering about that.” In addition to gaining a new skill and a new acquaintance, it seems Mary has also learned something new.

Others claim that Mary doesn’t learn something new but instead learns an old fact in a new guise. Learning that the liquid in your cup is water involves learning the same fact as learning that the liquid in your cup is H2O, but you could know one without the other. Perhaps what Mary learns is not a new fact but an old fact in a new way. Such people would deny 2, holding that Mary can learn every fact but not everything, because she cannot learn the old facts in a new guise.

Such analogies are spurious. The reason one can know that a liquid is water without knowing it’s H20 is that they don’t know some things about water or H2O. If you knew every fact about water and H2O (including that water is H2O) then if you knew something was water, you’d inevitably know that it’s H2O. As David Chalmers says (p.141):

We can also put the point a more direct way. Whenever one knows a fact under one mode of presentation but not under another, there will always be a different fact that one lacks knowledge of—a fact that connects the two modes of presentation.14 If one knows that Hesperus is visible but not that Phosphorus is visible (because one does not know that Hesperus is Phosphorus), then one does not know that one object is both the brightest star in the morning sky and the brightest star in the evening sky. This is a separate fact that one lacks knowledge of entirely. Similarly, if one knows that Superman can fly but not that Clark Kent can fly, then one does not know that there is an individual who is both the lead reporter at the Daily Planet and who wears a cape. If one knows that water is wet but not that H2O is wet, one does not know that the stuff in the lakes is made out of H2O molecules. And so on.

It’s common for physicalists to simply bite the bullet and say that Mary could know everything it’s like just by being in her black and white room. I find that view utterly crazy. If this is right, then if we had a good enough memory, just by reading about octopus brains, eventually we’d know what it’s like to be them and to see the exotic colors that they see but we cannot. That Mary learns when she leaves the room is about as obvious as anything could be.

Here, I’ve only given a brief sketch of some of the responses to Mary’s room and why I think they’re wrong. It’s a tricky argument to think through, but it’s prima facie devastating, and to my mind, no physicalist has yet told a convincing story of how Mary would remain ignorant of consciousness facts if she knows all the physical facts and consciousness facts simply are physical facts. So long as Mary learns something new when she exits the room and she knew everything physical, she must learn something non-physical about consciousness, in which case consciousness is not purely physical.

I think the weakest premise is the first one.

This thought experiment, like many other consciousness related ones, is trying to pump an intuition by expecting us to be on board with a premise that no person can possibly have any intuition about. I frankly think it's a little disingenuous that the set up includes a humble little scientist working from her humble little room reading her textbooks. *But* she also knows every single physical fact -- which, when taken seriously, makes her a godlike Laplacian demon. I don't think anyone can relate to that, and intuitions pumped through that relatability cannot be trusted.

I really enjoyed the post and I do agree with some of your criticisms of physicalists, but don't think this thought experiment is helping much.

"Mary in her black and white room can, merely by reading textbooks, learn everything physical. "

Can Mary also learn how to ride a bike merely by reading textbooks? If she can't learn how to bike, does that mean biking is not physical? (I mean regular biking - nothing like ET-style in the sky, magical biking.)

What if Mary could devise an apparatus like those used in Matrix (see the way Neo learns Kung-fu) and download the color red into her brain? Would that work?

I keep coming back to this premise: "Mary in her black and white room can, merely by reading textbooks, learn everything physical." It seems so demanding that it makes physicalism impossible. Because of course there are always things you can't just learn by reading textbooks.

I mean you could replace Mary the Scientist with Mary the AI Robot that is obviously physical. But even there may be purely "physical" things Mary the AI Robot wouldn't be able to learn just by reading textbooks and/or going through data.