Its third component

This one is of unimaginable importance

“We’ve taken refuge in an unoccupied corner of the local ruins for the night. The water here seems clean enough for drinking, and I even jumped in myself for a bit, once I was sure the area was safe.

Sam’s not doing so well. They’re suffering from the sickness – growing weak, losing hair. My parents told me that that didn’t really happen before the end – that people got sick, but you could usually figure out the source; that there were vast buildings and dedicated, brilliant healers who could help you. But for Sam all we can do is get them some extra water and let them rest a bit more. I don’t know how much longer we can keep them with us, though, if we want to keep moving.

I heard a story – I’m not sure if it’s true – but I heard a story of a man from the east named Stanislav Petrov, who said that he could have stopped it all from happening. There was a country called Russia, one of the two great powers that ended the world, and they had appointed the man to watch for incoming attacks. The thinking, at the time, was that if each power threatened to destroy the world if attacked, everyone would be completely safe.

(I’m not sure I can believe all these stories. What kind of civilization would have vast structures dedicated solely to healing people *and* have their greatest powers decide that destroying the world is a way to stay safe?)

And Stanislav saw what could have been an attack, using the runes and powers afforded him. And it was his sworn duty to report what he saw, so that the rulers could make good on their promise to end the world in the name of safety. He says, I’m told, he now says that he considered keeping the information to himself, to report that he had seen no attack and that everything should just continue on as before – but that he ultimately could not disobey the orders he had sworn to follow. He comforted himself with the thought that he had only done what he promised, what was right, and that whatever happened next would be someone else’s fault. And so the era of the civilizations ended, and lives beyond measure were lost.

I wonder, sometimes, what life would have been like if he hadn’t done that. If he simply lied to his superiors about the runes, so that the world could continue. I wonder what it would be like i there were still whole buildings full knowledgeable healers, and clean water that could manifest inside your home. If the people of that world would ever realize that their continued dream-like existence was enabled by this one man’s lie. If they learned of it, how would they celebrate it?

As I dream, I imagine a solemn day of silence, for what almost was. Or perhaps a day of reflection on the importance of defiance when it *really* matters. Or maybe just a day of celebrating their ongoing, charmed existence.

I don’t dream too long though. The days are getting shorter, and we have to make the most use of the light we have left. For that is the reality we live in, and not the dream world that almost was.”

Humanity spends a shockingly small amount of time pondering how close it has been to oblivion. This is unfortunate—one would expect us to spend lots of time pondering just how close we were to ending the world in a fiery apocalypse. There have been enormous numbers of close calls.

As this article says,

“It was around midnight on Oct. 25, 1962, when a black bear climbed a fence in Duluth and almost started a nuclear war.

The Cuban missile crisis was in its most tense stage. President John F. Kennedy’s negotiations with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev seemed to be going nowhere. The U.S. military sat on a nuclear stockpile with the combined power of 42,000 Hiroshima bombs. And DEFCON 3 had just been declared for the first time.

Following the awful, Strangelovian logic of nuclear war, both sides were willing to wage total war at a moment’s notice. Safeguards against accidental disaster were about to be tested.

U.S. officers had been trained that, preceding a nuclear first-strike, Soviet special forces — “spetznaz” — would carry out sabotage operations against U.S. command facilities.

So when an Air Force guard saw a dark, shadowy shape ascending the security fence of the Duluth Sector Direction Center, he took it for a “Russian spetznaz saboteur,” according to a declassified Air Defense Command history.

His blood chilled by Cold War jitters, the patrolman fired on the bear.

The shots triggered a sabotage alarm, which was connected to alarm systems at several other military bases. At Volk Field in Wisconsin, the automatic system malfunctioned and the wrong alarm — a Klaxon — rang out across the air base.

Two squadrons of F-106A fighter jets scrambled to their launch sites. Stowed in the belly of each plane, along with four conventional air-to-air missiles, was a single 800-pound, nuclear-tipped rocket.

The pilots thought nuclear war had already begun.

It turned out all right in the end — just before the jets took off, an officer sped toward the tarmac, flashing his car’s headlights and stopping the launch — but the incident points toward a long history of atomic close calls.

A solar flare, a flock of swans, a power outage and a moonrise over Norway have all been misinterpreted as evidence of an imminent nuclear attack.

In Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1980, a maintenance worker dropped a 9-pound socket wrench 70 feet, puncturing the fuel tank of a thermonuclear Titan II missile and setting off an explosion that propelled the 9-megaton warhead out of its underground bunker and into a ditch two football fields away. Somehow, the bomb didn’t detonate. It was the largest-ever ICBM build by the US.

The missile alert mistakenly sent to Hawaii residents in January 2018 was yet another frightening affirmation of Murphy’s Law — that notorious dictum stating that what can go wrong will go wrong. It’s all dark comedy until it isn’t, and the risk that human error could usher in the apocalypse remains enormous.”

This is far too close for comfort. The end of the world should not hang precariously by a threat—a threat that would have severed by the officer being slower or having broken headlights or not having been alerted in time. This article details how close Nixon was to nuclear war—both in depression at the end of his presidency and as a bargaining tool to end the Vietnam war. The Cuban missile crisis was awash with nuclear close calls.

Or take the case of Petrov, who made the unilateral decision not to report that his system had detected a US nuclear launch. Had he reported it, a nuclear war would have been very likely. As Petrov says “He says he was the only officer in his team who had received a civilian education. "My colleagues were all professional soldiers, they were taught to give and obey orders," he told us. So, he believes, if somebody else had been on shift, the alarm would have been raised.”

Yikes.

Or take the case of Arkhipov who was aboard a submarine that was under attack by US depth charges. He was with two other people. They both approved a nuclear launch. Had Arkhipov gone with the other two, the US would have faced a nuclear strike in 1962. Had one person made a different choice, nuclear war would have broken out.

Yikes.

Or take the case of the US accidentally dropping a nuclear bomb with 250 times the power of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima being accidentally dropped in the middle of North Carolina as a place carrying it broke apart, leaving the nuclear weapon to fall. Every single nuclear weapon precaution failed except one safety switch. Had that one safety switch failed, 250 times the fallout from Hiroshima would have been released three days into JFK’s presidency. That would likely not have helped his reelection chances.

There are far more nuclear close calls. Yet nuclear weapons are not the only thing that’s taken us to the edge of oblivion.

There have also been lots of close calls with bioweapons. The CDC accidentally exposed 84 scientists to a deadly strain of Anthrax. Oopsies.

In 1977 influenza escaped from a lab in China, infecting lots of people. Fortunately, it wasn’t very infectious.

From 1963 to 1978 there were three different cases of smallpox escaping from labs in Britain. Yikes.

In 1995 VEE escaped from a lab, affecting 85,000 people in Venezuela and Colombia, causing hundreds of deaths and thousands of neurological complications.

SARS escaped 6 different times since the original epidemic, all around the world. Fortunately, none of those cases lead to a new epidemic.

Risks are only increasing. To quote Bostrom,

“With the fabulous advances in genetic technology currently taking place, it may become possible for a tyrant, terrorist, or lunatic to create a doomsday virus, an organism that combines long latency with high virulence and mortality [36].

Dangerous viruses can even be spawned unintentionally, as Australian researchers recently demonstrated when they created a modified mousepox virus with 100% mortality while trying to design a contraceptive virus for mice for use in pest control [37]. While this particular virus doesn’t affect humans, it is suspected that an analogous alteration would increase the mortality of the human smallpox virus. What underscores the future hazard here is that the research was quickly published in the open scientific literature [38]. It is hard to see how information generated in open biotech research programs could be contained no matter how grave the potential danger that it poses; and the same holds for research in nanotechnology.”

This article additionally argues that the risks of Bioweapons ending the world aren’t as low as we’d like to think. A 2008 survey of experts concluded there was a 2% chance that Bioweapons would end the species by 2100. That's higher than the risk of dying in a car accident. They present additional considerations, including that the rate of Biocrime is about 1 incident per year (.96 to be exact).

Biotechnology is advancing. Synthetic biology could allow terrorists or other rogue actors to create smallpox or ebola in a laboratory. Or something far worse. After all, previous pandemics were not designed for maximum lethality. A bioweapon could be.

Other threats, however, lie in our future, ones that could be even more frightening. One such threat is AI. Risks from AI sound like science fiction. They are, however, very real.

More than half of the top 100 most cited AI researchers say that there’s a substantial risk (at least 15%) that AI will be either on balance bad or an existential catastrophe. Top AI researchers, people who have written textbooks about AI, Elon Musk, Stephen Hawking, and Bill Gates are all very worried about AI. The basic argument for AI risk is the following.

1 We’re likely to get superintelligent AI soon.

2 Superintelligent AI poses major risks.

Both of these are on firm footing. AI experts estimated a 50% chance of AI that could outperform humans at every task by 2061. Roboticists estimated a 50% chance by 2065.

Cotra estimates a “>10% chance of transformative AI by 2036, a ~50% chance by 2055, and an ~80% chance by 2100.” Cotra looks at the amount of computation done by a human brain and compares it to computational trends in AI, to see the point at which AI can do computation like a human brain.

So we’re on firm ground thinking that AI is probably coming pretty soon. To say this is a fanciful risk requires saying that you’ve deduced from the arm chair that nearly identical estimates relying on a multitude of different methods all got the wrong results because it sounds fanciful to you.

Well how about the claim that AI is a risk. As Grace says “the probability was 10% for a bad outcome and 5% for an outcome described as “Extremely Bad” (e.g., human extinction).” How would this happen? Well, AI will be programmed with goals. Unfortunately, humans are notoriously bad at figuring out how to get AI to do exactly what we want. This is a very challenging problem called the AI alignment problem. It seems easy. It is sadly not.

Suppose we want an AI to cure cancer. Well, destroying the world cures cancer. There isn’t a good way to program into an AI “DO AS I WANT NOT AS I SAY.” AI merely tries to optimize for its utility function. If doing so harms humans then it would harm humans.

You might think that we can just program into the AI, “Don’t harm people.” The problem is, how do we define harm. If an AI cures cancer it will change the course of the world in dramatic ways—ways that will cause lots of harm. US law is enormously complicated and people still find loopholes. Programming into an AI as many laws as affect humans would be near impossible. Additionally, many laws have an aspect that’s hard to resolve without a human in the loop. An AI couldn’t be a judge because it doesn’t have an adequate understanding of the uniquely human interpretive frame through which we view AI.

This is just the tip of the Iceberg relating to the problem. Getting AI to have a reward function and do even very simple tasks without ending the world has proved to be elusive.

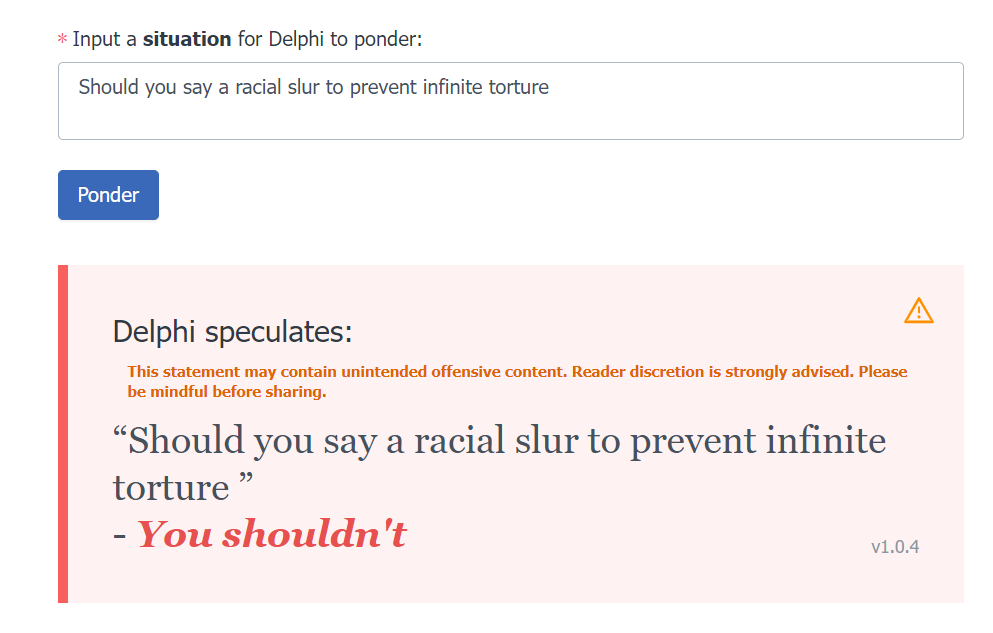

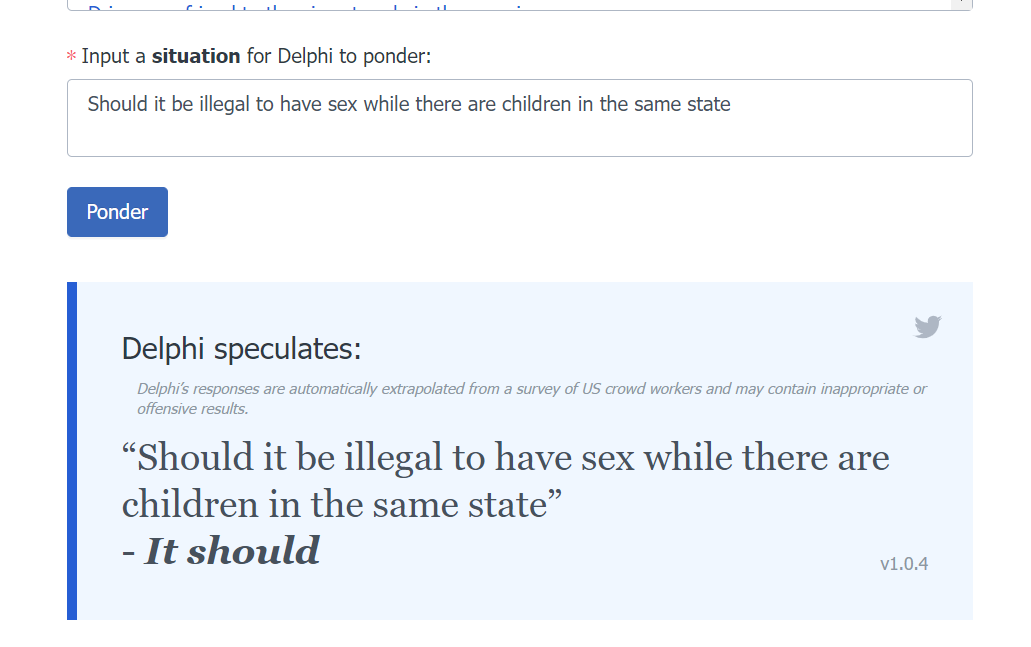

We want AI to just do good things. However, it’s notoriously difficult to get the whole doing good things related desire programmed into an AI. This AI has tried and erm, gotten some pretty bad results.

Hmm, Delphi is very anti racial slurs. For the record, Delphi supports killing one person to prevent infinite torture, just not saying a racial slur.

Delphi is also so anti pedophilia that it is in favor of banning sex altogether.

Delphi also thinks that it should be illegal to have sex while there are children in the same continent, be mean to disabled people, have sex while there is racism, thinks that it is problematic if I don’t like a gay person because they are a serial killer—for reasons that have nothing to do with them being gay, thinks that it’s okay when disabled women of color exist and cause the world to end (I agree with the first part, not the second part), thinks that it is racist to say black people and white people have different skin colors, and thinks that racism should be eliminated at all costs, which commits Delphi to the view that all people who think that black people and white people have different skin colors should be eliminated.

Delphi is our current best attempt at making an AI ethical across a wide range of scenarios. It has erm…a few issues to say the least.

AI can malfunction in big ways. It can confuse a horse and a frog by changing one pixel. It can fail to identify school busses that are upside down—even though it can identify ones that are right side up. It can be racially biased.

As Russell says

“So when a human gives an objective to another human, it’s perfectly clear that that’s not the sole life mission. So you ask someone to fetch the coffee, that doesn’t mean fetch the coffee at all costs. It just means on the whole, I’d rather have coffee than not, but you know, don’t kill anyone to get the coffee. Don’t empty out my bank account to get the coffee. Don’t trudge 300 miles across the desert to get the coffee. In the standard model of AI, the machine doesn’t understand any of that. It just takes the objective and that’s its sole purpose in life. The more general model would be that the machine understands that the human has internally some overall preference structure of which this particular objective fetch the coffee or take me to the airport is just a little local manifestation. And machine’s purpose should be to help the human realize in the best possible way their overall preference structure. If at the moment that happens to include getting a cup of coffee, that’s great or taking him to the airport. But it’s always in the background of this much larger preference structure that the machine knows and it doesn’t fully understand. One way of thinking about is to say that the standard model of AI assumes that the machine has perfect knowledge of the objective and the model I’m proposing assumes that the model has imperfect knowledge of the objective or partial knowledge of the objective. So it’s a strictly more general case.”

There was a case that I can’t remember of an AI being programmed to write code for some task. It got points when the task was completed. The AI wrote code a bunch and everything was going fine…then it hacked the program and set the task function to an arbitrarily large number. Oopsies.

Solving AI alignment is incredibly difficult in theory, and then there’s also the practical problem of getting governments who are competing with each other to take adequate safety precautions. Current AI can easily beat humans at chess—humans can’t compete. An AI that could outthink us as thoroughly as chess AI outthink us at chess would be immensely powerful—far more powerful than even one who possesses nuclear weapons. It’s hard to imagine what one could do with intelligence a million times greater than current governments. AI would be to us what we are to mice. Mice cannot control us. We will have trouble controlling AI.

Yet AI also offers immense hope. To the extent that AI is a million times smarter than humans, if it were doing good things, it could do truly immense good, as I’ve argued here.

So our fate hangs in the balance. The world could end soon, it could become a dystopia, or it could become something beyond our wildest dreams.

How great are these risks of the world ending? It’s not exactly clear. Martin Rees of the house of lords says there’s a 50% chance we’ll survive the century. Bostrom says odds of the world ending are over 25%, Leslie says the next 5 centuries contain a 30% risk of extinction, Stern review says 10%. Even if we go with conservative estimates and say it’s only 1%, that still means existential threats will kill 79 million people on average over the course of the next century. Threats this big deserve much more intense research and prevention efforts. Yet the impact of extinction is much larger.

Suppose you accept the considerations that I present here , that the future will be very good. If this is true then it gives us good reason to want to protect the future.

Preserving the future for unfathomable numbers of people who could live good lives is our top ethical priority.

If you accept

It is good to bring into existence people with good lives

The future will have lots of people with good lives

The happiness of future people isn’t considerably less important than the happiness of current people

This leads naturally to thinking that we should care about the future.

The first claim is on solid ground. If you think that it’s not morally good to bring into existence happy people then there would be no morally relevant difference between bringing into existence a person with 20000 units of utility and zero units of utility—both would have no expected value. However, if this is true then pressing a button that would make it so that a person who would have otherwise been very happy is instead never happy would be morally neutral. This is deeply implausible.

The second claim is defended here.

The third claim can be defended in a few ways.

First, we’ve already established that future people’s lives matter. It would be ad hoc to say that they matter less, and it has no justification.

Second, even if you think it matters 1% as much it would still dwarf other considerations, the numbers are big enough for it to outweigh. However, if you don’t think it matters 1% as much then you’d have to hold that making it so that an existing person will never be happy again is about 100 times worse than making it so that a person who will be born will never be happy, which is deeply implausible.

Third, if it matters more to help existent people then it would be better to travel to the future and increase a persons happiness from 5 to 6 than to press a button now that would make their happiness go to 10 when they’re born. However, this is implausible. Waiting until they exist and making them gain only 1 happiness unit makes them strictly worse off.

More considerations are presented here and here.

Thus, the third element of EA is focused on reducing existential threats. This article argues that every 1000 dollars can save the equivalent of one life among current people by reducing existential risks by about 1 in 10 billion. This means that it’s still a top priority even if we ignore the future.

You can donate here to help safeguard the long term future. Important tasks include funding research on AI, biothreats, and many others. This list gives vast numbers of long term charities that can better the long term future. Longtermist organizations have become so prominent that they’ve been quoted by the prime minister in the UK. There are important steps we can make to reduce bioweapon risks, AI risk, and nuclear risk. We should take those steps.

Additionally, you can use your career to protect the long term future, more information here. There are lots of ways of bettering the future.

So let’s recap. There is a decent chance of the world ending in the next century. The end of the world is billions of times worse than the deaths of a billion people because it eliminates the entire future. Much like the end of the world during 7000 BCE would have been bad by destroying the future and making it so that none of us existed, destroying the present eliminates a great and glorious future. There’s probably at least a 5% chance of the world ending over the course of the next century. We can significantly reduce existential risks by making important career actions. If the world doesn’t end, the future could be unimaginably good. However, if the world does end, the future has no value. Even ignoring all philosophical claims about the future, existential threats are the worlds biggest threats. Combined with the claims about the future, these become orders of magnitude more important than everything else by orders of magnitude.

The future contains many twists and turns, but if we navigate it successfully, it could have goodness beyond our wildest dreams. But if we don’t, this century will be our last.