Erik Hoel's Mistaken Criticism of Effective Altruism

"You shouldn’t kill people, even if it seems like a good idea at the time."

Those of us who are trying to use evidence and data to make the world maximally better are called effective altruists. It turns out that we as individuals have extraordinary opportunities — individual middle class donors can save hundreds of lives and improve the conditions of tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of farm animals. We can also make enormous progress in improving the future.

This is a really incredible fact. Most people throughout human history have not been able to save as many people as the worst serial killers can kill. We can do so much good that combined with the evils of a serial killer, the world is still a better place for the both of us having existed. We really should take these incredible opportunities.

This doesn’t require any super controversial philosophical conclusions. You don’t have to support killing someone to save two random strangers, or think no-one has rights, or think that we should feed all the world’s resources to a utility monster if they existed. Of course, you should think all of those things, as I’ve argued elsewhere, but you certainly don’t have to. You just have to accept that it’s good to do good things.

Erik Hoel has an article criticizing the utter common-sense ideas of effective altruism. His subtitle is “morality is not a market.” Let’s start by addressing this criticism — that EA turns goodness into a market.

It’s not an objectionable form of turning morality into a market when doctors, in triage, save the patients who are most immediately at risk. We are still in triage. When there are millions dying, it makes sense to put our resources where they can do the most good. Call that making morality a market if you’d like, but it’s really just caring about saving lives and doing lots of good.

Hoel starts his critique by quoting Russell, but replacing Russell’s use of the term Christian for the term Effective altruist.

Some people mean no more by it than a person who attempts to live a good life. In that sense I suppose there would be effective altruists in all sects and creeds; but I do not think that that is the proper sense of the word, if only because it would imply that all the people who are not effective altruists—all the Buddhists, Confucians, Mohammedans, and so on—are not trying to live a good life. I do not mean by an effective altruist any person who tries to live decently according to his lights. I think that you must have a certain amount of definite belief before you have a right to call yourself an effective altruist.

I don’t think anyone has said that effective altruists are just those who try to live good lives. A serviceable definition of an effective altruist is one who dedicates a reasonable amount of effort to making the world a better place as effectively as possible. Most people never even consider the question of how they should do the most good — the few people who are part of the effective altruism movement have been able to save hundreds of thousands of lives.

Effective altruism is one of those things that is really obvious and snowballs into some things that are not obvious. Consider the following analogy: suppose that someone pointed out that some ways of improving your health are hundreds or thousands of times more effective than others. Sure, lots of people try to diet, but actually just eating a carrot a fruit a day reduces cancer risks by 99% and dramatically improves health. (Note, these health facts are obviously false).

In response to this, there are lots of complicated questions raised. Should you just eat fruit? How much fruit should you eat? What are the best fruits. But the basic idea is clear — you should eat fruit, because you can benefit yourself a ton at minimal cost. EA is similar — but you can benefit others enormously at minimal personal cost, rather than yourself.

It’s a pretty obvious idea, but so few do it. It’s one of those low-hanging fruit ideas — pun intended — that gives you an enormous bang for your buck. Lots of people hear it think ‘hmm, that’s a nice idea,’ and then they ignore it. So as a result, despite it being very low-hanging fruit, it goes unpicked — those who do pick the fruit still can save hundreds of lives.

Hoel goes on to claim that the philosophical underpinnings of effective altruism are very shaky. We’ll see about that.

For despite the seemingly simple definition of just maximizing the amount of good for the most people in the world, the origins of the effective altruist movement in utilitarianism means that as definitions get more specific it becomes clear that within lurks a poison, and the choice of all effective altruists is either to dilute that poison, and therefore dilute their philosophy, or swallow the poison whole.

This poison, which originates directly from utilitarianism (which then trickles down to effective altruism), is not a quirk, or a bug, but rather a feature of utilitarian philosophy, and can be found in even the smallest drop. And why I am not an effective altruist is that to deal with it one must dilute or swallow, swallow or dilute, always and forever.

But effective altruism doesn’t have to be utilitarian. All you have to accept is beneficentrism — the idea that it’s important to do lots of good — to be an effective altruist. Consider the three main things that effective altruists do.

Improve global health and development — saving lots of lives at low cost by donating to effective charities. You sure as heck don’t have to be a utilitarian to think that it’s good when rich westerners give their money to prevent a death from malaria at the cost of only around 5000 dollars. Thinking that’s more important than, for example, donating to ineffective domestic charities is just common-sense.

Combatting factory farms. The cost to save an animal from the torturous conditions of factory farms is less than a dollar. Given the overwhelming horrors of factory farms, this is obviously incredibly good. Just as it’s incredibly good to prevent the torture of multiple dogs at the cost of a dollar, the same is true with factory farmed animals — the victims of mankind’s worst atrocity.

Reducing Existential risks. This can be done at low cost — a estimate by Todd concluded every 1,000 dollars can reduce existential risks by about 1 in 10 billion, saving around 1 life. While the exact numbers can be disputed, it’s very obvious that reducing the risks of the end of the world is a very good thing.

Hoel then launches into a rapid series of errors.

The current popularity of effective altruism is, I think, the outcome of two themselves popular philosophical thought experiments: the “trolley problem” and the “shallow pond.” Both are motivating thought pumps for utilitarian reasoning.

These are intuition pumps for various conclusions that utilitarianism would agree with, namely, that one should donate a lot of money to charity and flip the switch in the trolley problem. The trolley problem isn’t even a thought experiment to motivate utilitarianism — it’s just to settle intuitions about which actions count as impermissible killing.

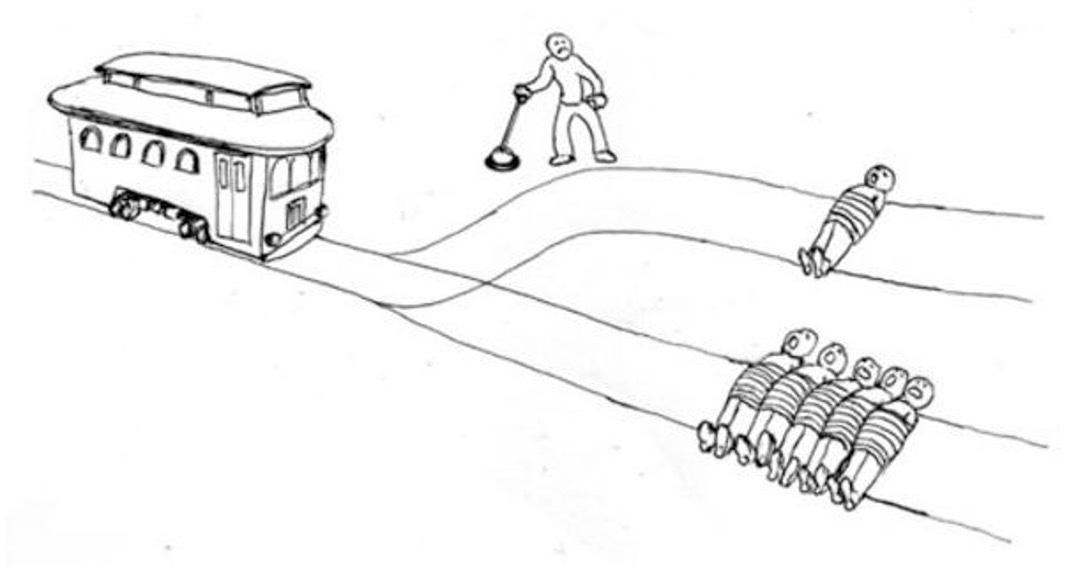

The trolley problem is a meme almost everyone knows at this point: a trolley is about to run over five people. Do you switch it to a different track with one person instead?

I remember first being introduced to the trolley problem in college (this was B.M., “Before Memes”). People were asked to raise our hands if we would pull the lever to switch the tracks, and the majority of people did. But then the professor gave another example: What if instead you have the opportunity to push an obese person onto the tracks, and you somehow have the knowledge that this would be enough slow the trolley and save the five? Most people in class didn’t raise their hands for this one.

Maybe all those people just didn’t have the stomach? That’s often the utilitarian reply, but the problem is that alternative versions of the deceptively simple trolley problem get worse and worse, and more and more people drop off in terms of agreement. E.g., what if there’s a rogue surgeon who has five patients on the edge of organ failure, and goes out hunting the streets at night to find a healthy person, drags them into an alley, slits their throat, then butchers their body for the needed organs? One for five, right? Same math, but frankly it’s a scenario that, as Russell said of forcing inexperienced girls to to bear syphilitic children: “. . . nobody whose natural sympathies have not been warped by dogma. . . could maintain that it is right and proper that that state of things should continue.”

I’ve defended this conclusion in various places. But this is all irrelevant to EA — you really don’t have to be a utilitarian to think it’s important to save kids from malaria. You certainly don’t have to be the rare type of hedonic act utilitarian who would accept the organ harvesting conclusion to be on board with EA.

The poison for utilitarianism is that it forces its believers to such “repugnant” conclusions, like considering an organ-harvesting serial killer morally correct, and the only method of avoiding this repugnancy is either to water down the philosophy or to endorse the repugnancy and lose not just your humanity, but also any hope of convincing others, who will absolutely not follow where you are going (since where you’re going is repugnant). The term “repugnant conclusion” was originally coined by Derek Parfit in his book Reasons and Persons, discussing how the end state of this sort of utilitarian reasoning is to prefer worlds where all available land is turned into places worse than the worst slums of Bangladesh, making life bad to the degree that it’s only barely worth living, but there are just so many people that when you plug it into the algorithm this repugnant scenario comes out as preferable.

This is one case where Hoel really drops the ball. He just totally ignores all of the literature around the repugnant conclusion — literature which leads moderate deontologists like Huemer to accept it. Parfit didn’t raise the repugnant conclusion as a reductio to utilitarianism, he used it as the culmination of a chain of reasoning, wherein each step seemed right, but the end seemed wrong. Parfit spent years being troubled by this, before coming up with what he thought was a solution, but which I don’t think works, and which has not been embraced by the literature. There is no widely accepted solution to the repugnant conclusion. Also, everyone in the real world, except Hoel apparently, would agree that overpopulating the world like that and putting everyone in slums wouldn’t actually be the best way to gain utility — this misstates the objection; the objection is that a hypothetical world with 10 billion in paradise would be worse than an arbitrarily large number of people with lives barely worth living.

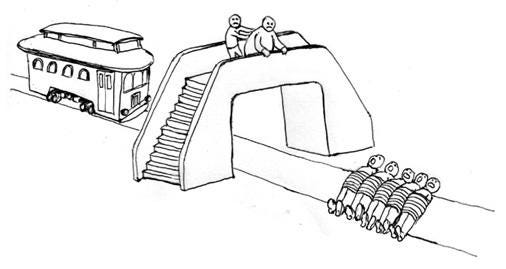

To see the inevitability of the repugnant conclusion, consider the other popular thought experiment, that of the drowning child.

This is a bizarre refrain. Both the conclusion arrived at from the drowning child and the repugnant conclusion strike some people as repugnant, but they have nothing to do with each other.

Written in the wake of a terrible famine in Bengal, Peter Singer gives the reasoning of the thought experiment in his “Famine, Affluence, and Morality.”

. . . if I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out. This will mean getting my clothes muddy, but this is insignificant, while the death of the child would presumably be a very bad thing. . . It makes no moral difference whether the person I can help is a neighbor's child ten yards from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away.

And all that sounds very good—who would not soil their clothes, or pay the equivalent of a dry cleaning bill, to save a drowning child?

He’s getting it, by George, he’s getting it. There are people dying, much like Singer’s drowning children, who we can save at minimal personal cost. If you can save lives at minimal personal cost, you should do so. Now, it doesn’t matter that they’re far away, or that they look different, or that the process is more direct. If we saved drowning children through a complicated indirect method, it wouldn’t be less good. Similarly, if you had really long arms to save drowning children, it wouldn’t be less good just because they’re far away. To argue against the drowning child argument, Hoel should point out some relevant difference between saving drowning children and children dying of malaria. What he shouldn’t do is point out that this is an inconvenient truth, and involves people not living up to their duties, and means that we should be doing more good. And he won’t do that, right?

Right??

But when taken literally it leads, very quickly, to repugnancy. First, there’s already a lot of charity money flowing, right? The easiest thing to do is redirect it. After all, you can make the same argument in a different form: why give $5 to your local opera when it will go to saving a life in Bengal? In fact, isn’t it a moral crime to give to your local opera house, instead of to saving children? Or whatever, pick your cultural institution. A museum. Even your local homeless shelter. In fact, why waste a single dollar inside the United States when dollars go so much further outside of it? We can view this as a form of utilitarian arbitrage, wherein you are constantly trading around for the highest good to the highest number of people.

A few things are worth noting. First, just pointing out that some philosophical argument has some conclusion that is unfortunate is not an objection to it. If you dispute no steps in the reasoning, then you need a pretty damn good reason to dispute the conclusion — which Hoel doesn’t have. Pointing out that it’s such a shame that morality says that if you donate to your operahouse instead of saving kids, when you have the opportunity to prevent deaths, is not much of an argument.

Second, you don’t have to be convinced by the drowning child argument to be an effective altruist. Even if people who don’t donate to save children doing something as bad as walking past drowning children, doing nothing, it’s still obviously good to save lives at minimal personal cost. You don’t have to accept any more controversial philosophical assumption to accept that incredibly minimal and obvious claim.

But we can see how this arbitrage marches along to the repugnant conclusion—what’s the point of protected land, in this view? Is the joy of rich people hiking really worth the equivalent of all the lives that could be stuffed into that land if it were converted to high-yield automated hydroponic farms and sprawling apartment complexes? What, precisely, is the reason not to arbitrage all the good in the world like this, such that all resources go to saving human life (and making more room for it), rather than anything else?

There are obvious practical issues with cramming millions of poor people into destroyed land, particularly if we’re longtermists. But there’s really no need to go into the details — once again, you don’t have to accept “arbitraging” all the worlds resources to do good. You just have to accept that it’s good to dramatically benefit the world — saving lives and such — at minimal personal cost. Hoel just totally misses this crucial point. He misses the forest for the trees — in this case, the trees are the interesting philosophical rabbitholes that some can go down related to EA.

The end result is like using Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World as a how-to manual rather than a warning. Following this reasoning, all happiness should be arbitraged perfectly, and the earth ends as a squalid factory farm for humans living in the closest-to-intolerable conditions possible, perhaps drugged to the gills.

This is obviously not the happiest, best, and most flourishing future.

And here is where I think most devoted utilitarians, or even those merely sympathetic to the philosophy, go wrong. What happens is that they think Parfit’s repugnant conclusion (often referred to as the repugnant conclusion) is some super-specific academic thought experiment from so-called “population ethics” that only happens at extremes. It’s not. It’s just one very clear example of how utilitarianism is constantly forced into violating obvious moral principles (like not murdering random people for their organs) by detailing the “end state” of a world governed under strict utilitarianism. But really it is just one of an astronomical number of such repugnancies. Utilitarianism actually leads to repugnant conclusions everywhere, and you can find repugnancy in even the smallest drop.

My above comments apply. Additionally, putting aside the question of defending effective altruism, and instead just defending utilitarianism, I’ve written extensively defending nearly all of the allegedly repugnant conclusions of utilitarianism.

Hoel next spends some time getting outraged about the torture vs dust specks conclusion — something irrelevant to EA, and which I think we all must rationally accept, as I’ve argued here.

The other popular response to the poison is one that I personally find more palatable, albeit still unconvincing, which is its dilution. I say palatable because, as utilitarianism is diluted, it loses its teeth, and so becomes something amorphous like “maximize the good you want to see in the world, with good defined in a loose, personal, and complex way” or “help humanity” or “better the world for people” and almost no one can disagree with these sort of statements. In fact, they verge on vapidity.

It’s not vapid if no one does it. If everyone agrees in a sort of amorphous, abstract way, that it would be great if we donated to combat malaria, then it’s not some vapid triviality — it’s a moral truth of vital importance. We should want everyone to know about it ASAP.

Proponents of dilution admit that just counting up the atomic hedonic units of pleasure or pain (or some other similarly reductive strategy) is indeed repugnant. Perhaps, they say, if we plugged in meaning to our equations, instead of merely pleasure or suffering, or maybe weighted the two in a some sort of ratio (two cups of meaning to one cup of happiness, perhaps), this could work! The result is an ever-complexifying version of utilitarianism that attempts to avoid repugnant conclusions by adding more and more outside and fundamentally non-utilitarian considerations. And any theory, even a theory of morality, can be complexified in its parameters until it matches the phenomenon it’s supposed to be describing.

This is a confused way of thinking about it. Lots of EAs are utilitairans. Many EAs, however, are not. With this being the case, they’re not diluting their moral theory just for EA — rather, they have a moral theory, and this tells them that it’s good to make the world dramatically better. Additionally, these moral theories don’t have to be “an ever-complexifying version of utilitarianism,” it just has to be any moral theory that accepts that it’s important to do lots of good, and that we should do more good rather than less.

Hoel next enumerates various possible ways of tweaking the theory. I’m a bullet biting hedonic act utilitarian, so I don’t think any of these ways are good. But fine, tweak the theory all you want — just don’t abandon the victims of malaria and factory farms.

Which brings me to effective altruism. A movement rapidly growing in popularity, indeed, at such a pace that if it somehow maintains it, it may have as much to say about the future of morality as many contemporary religions. And I don’t think that there’s any argument effective altruism isn’t an outgrowth of utilitarianism—e.g., one of its most prominent members is Peter Singer, who kickstarted the movement in its early years with TED talks and books, and the leaders of the movement, like William MacAskill, readily refer back to Singer’s “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” article as their moment of coming to.

Lots of EAs are utilitarians. I think around three quarters, if I remember correctly. But lots of Democrats are Christians. So are lots of union members. Nonetheless, criticizing Christianity doesn’t criticize Democrats. To criticize EA, you should be able to point to bad things that it’s doing. Doing right things based on the guidance of a wrong moral theory is fine.

The leaders of the movement are mostly morally uncertain people — not full on utilitarians. They just like Singer a lot.

Additionally, it doesn’t matter how a movement originated. The democratic party has pretty nasty origins. This doesn’t mean the actually existing democratic party is a bad thing. To figure this out, one needs to look at what they’re actually doing.

This means that, at least in principle, to me effective altruism looks like a lot of good effort originating in a flawed philosophy. However, in practice rather than principle, effective altruists do a lot that I quite like and agree with and, in my opinion—and I understand this will be hard to hear over the sound of this much criticism, so I’m emphasizing it—effective altruists add a lot of good to the world. Indeed, their causes are so up my alley that I’m asked regularly about my positions on the movement, which is one reason I wrote this. I think the effective altruist movement is right about a number of things, not just AI safety, but plenty of other issues as well, e.g., animal suffering. But you don’t have to be an effective altruist to agree with them on issues, or to think they have overall done good.

This is a common mistake when thinking about EA — thinking about it as a philosophy. EA is not a general world philosophy. It doesn’t tell you how to vote, whether to believe in god, or what to do in the trolley problem. It just implores you to save lives — when you can at minimal cost — and benefit the world in other ways.

One can see repugnant conclusions pop up in the everyday choices of the movement: would you be happier being a playwright than a stock broker? Who cares, stock brokers make way more money, go make a bunch of money to give to charity. And so effective altruists have to come up with a grab bag of diluting rules to keep the repugnancy of utilitarianism from spilling over into their actions and alienating people. After all, in a trolley problem the lever is right in front of you and your action is compelled by proximity—but in real life, this almost never happens. So the utilitarian must begin to seek out trolley problems. Hey, you, you’re saving lives in Nigeria? How about you go to Bengal? You’ll get more bang for your buck there. But seeking out trolley problems is becoming the serial killer surgeon—you are suddenly actively out on the streets looking to solve problems, rather than simply being presented with a lever.

Hoel doesn’t elaborate on why earn to give is repugnant. It seems obvious that if you have two possible career choices, and one of them can save dozens of extra lives, you should pick that one! It’s not clear why this is repugnant. This is especially so when we consider the drowning pond analogy.

But, once again, you don’t have to support earn to give to believe in EA. You can think you should choose the playright jobs — and also that people should try to make the world a lot better. If you think earning to give sucks, this should make you more reluctant to earn to give, but it shouldn’t make you less opposed to any other core tenets of EA.

Therefore, the effective altruist movement has to come up with extra tacked-on axioms that explain why becoming a cut-throat sociopathic business leader who is constantly screwing over his employees, making their lives miserable, subjecting them to health violations, yet donates a lot of his income to charity, is actually bad.

There are plausible utilitarian reasons not to do this. SBF shows this well — violating common-sense morality tends to have bad outcomes.

To make the movement palatable, you need extra rules that go beyond cold utilitarianism, otherwise people starting reasoning like: “Well, there are a lot of billionaires who don’t give much to charity, and surely just assassinating one or two for that would really prompt the others to give more. Think of how many lives in Bengal you’d save!” And how different, really, is pulling the trigger of a gun to pulling a lever?

This wouldn’t work, would have disastrous PR implications, and would be unsustainable. Billionaires would just hire security. History is clear that if you think you’re above general moral heuristics, you’re probably wrong. You shouldn’t kill people, even if it seems like a good idea at the time.

For when I say the issues around repugnancy are impossible to avoid, I really mean it. After all, effective altruists are themselves basically utility monsters. Aren’t they out there, maximizing the good? So aren’t their individual lives worth more? Isn’t one effective altruist, by their own philosophy, worth, what, perhaps 20 normal people? Could a really effective one be worth 50? According to Herodutus, not even Spartans had such a favorable ratio, being worth a mere 10 Persians.’

It depends on what you mean by more moral worth. If you mean more intrinsic moral worth, such that comparable benefits are more important, then all have equal worth. If you mean more moral worth in the sense that you should save them instead of two strangers, because they will save hundreds of strangers, then I think the answer is yes. If you can either save 2 people or 1 person — but the one will save a hundred others, you should save the 1. But again, you don’t have to think any of that to be an EA. Say it with me — you just have to think we should try to do lots of good, as effectively as possible.

Of course, all the leaders of the effective altruist movement would at this point leap forward to exclaim they don’t embrace the sort of cold-blooded utilitarian thinking I’ve just described, yelling out—We’ve said we’re explicitly against that! But from what I’ve seen the reasoning they give always comes across as weak, like: uh, because even if the movement originates in utilitarianism unlike regular utilitarianism you simply aren’t allowed to have negative externalities! (good luck with that epicycle). Or, uh, effective altruism doesn’t really specify that you need to sacrifice your own interests! (good luck with that epicycle). Or, uh, there’s a community standard to never cause harm! (by your own definition, isn’t harm caused by inaction?). Or, uh, we simply ban fanaticism! (nice epicycle you got there, where does it begin and end?). So, by my reading of its public figures’ and organizations’ pronouncements, effective altruism has already taken the path of diluting the poison of utilitarianism in order to minimize its inevitable repugnancy, which, as I’ve said, is a far better option than swallowing the poison whole.

Here’s one option that sacrifices none of the movements aims — be a Huemerian deontologist. Think that people have rights, you shouldn’t violate them except for enormous benefits. Thus, harvesting someone’s organs is wrong. Again, EA is not a general philosophy, it makes a much more limited claim — help the malaria kids and do other impactful, good things.

I mean, who, precisely, doesn’t want to do good? Who can say no to identifying cost-effective charities? And with this general agreeableness comes a toothlessness, transforming effective altruism into merely a successful means by which to tithe secular rich people (an outcome, I should note, that basically everyone likes).

If basically everyone, presumably including Hoel, likes the way that EA plays out in the real world, EA is good. If lots of people form a movement and have confused philosophical beliefs, but with those they spend their time doing good exclusively, then that’s a pretty good movement.

The trouble with attacking effective altruism is that almost any valid critique can be incorporated into the system quite easily. After all, if there's some argument for why EA right now is ineffective, EA's own mandate is to consider the criticism and use it to improve efficiency.

In order to defeat it, you need to contrive something that would be difficult to arrive at if you weren't just looking for some pretext to oppose effective altruism.

That is why I am a proud member of EA's only successful opponent: The Center for Effective Evil. Our latest program is a 1,000,000$ grant to a recently fired Meta Engineer to develop AGI designed to make all his enemies suffer. Hopefully, it interprets that statement to include all life on earth (or the universe [or the multiverse]).

Thanks for this. I've added a link to it in my blog on the topic

https://www.mattball.org/2022/11/lay-off-effective-altruists.html

Note: I think publishing during this time (the holidays) often minimizes readership.