Edit: AITC feels I misrepresented him on points—see the comments for more discussion.

I recently debated frequent substack commenter

(henceforth AITC) about anthropics. He left so many comments leading to lengthy, tangled back-and-forths that I decided it would be most efficient to simply debate him. Here’s his lesswrong page where he’s written a bit about it. For my writing on the subject, see here, here, here, and here.I think I was probably a bit too cantankerous during the debate. Sorry! I’ve become jaded by thousands of confused comments talking about anthropics that I feel morally bound to respond to that I’m probably too quick to get annoyed when I think people are being confused about anthropics. This is a vice!

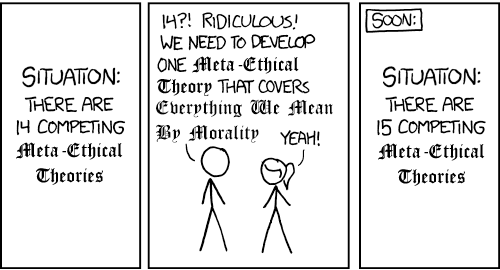

I still don’t quite understand what his view is supposed to be. He says it’s “just applying probability theory to your anthropics.” Incidentally, I think that’s what SIA does. But probability theory alone isn’t enough to tell you the right anthropic view—I’m reminded of an old Scott Alexander meme:

(Replace meta-ethical theory with anthropic theory that just involves applying probability theory to anthropics).

AITC thinks that so long as two theories both predict you’d exist at least once with your experiences, you shouldn’t treat your existence as confirming either. But this is super counterintuitive. To repeat a case I gave in the video, suppose you’ll be woken up 100 billion days, each time with no memory of previous days. Each day, you’ll roll a die with a million sides. Before you’re put to sleep, a coin is flipped: if it comes up heads, all the dice are rigged so that they’ll always come up 483,333. If it comes up tails, they’re all fair dice.

You wake up without memories of the previous days and roll dice. On AITC’s view, you shouldn’t think it’s much likelier that the coin came up heads than tails—whether it came up heads or tails, you’d at some point roll 483,333. Thus, heads and tails are roughly equally likely. But this is nuts! Before rolling the die, the odds it will come up 483,333 are 100% if it came up heads while 1 in a million if it came up tails. It coming up 483,333 should thus give you a massive update in favor of heads.

Now, the reason AITC doesn’t buy this is that he says that you can’t have credences in de se facts. A de se fact is a fact not about what the world is like but about your place in the world. Imagine, to give a case from Lewis, that there are two identical gods located on opposite sides of the world. They might know every fact about what happens in the world but not know which God they are—they may not know whether they’re the god on the left or the right. On AITC’s view, this is an empty, incoherent question—the sort of thing one can’t have credences about.

But this just seems mad! Surely you can think “I know such and such will happen in total history, but which will happen to me.” We can imagine that one of the gods will die after 1,000 years—it seems coherent for the Gods to assign credences to them dying rather than the other one. One AITC’s view, one of the gods can’t have a credence in dying after 1,000 years! The gods cannot think “it’s likelier that I’ll die after 1,000 years than that I’ll get 400 royal flushes in poker,” for they can’t even assign a probability to such a thing. Nuts! And AITC’s only argument for this is that it can’t be modeled as a probability space over what things will happen, but of course it can’t—de se facts are, by definition, the facts not about what will happen but about your place in the world.

I think you can assign probabilities—perhaps imprecisely—to any proposition, any fact about the world. Yet clearly there are de se facts. There’s a fact about whether I or my twin in an identical universe will die.

It gets even worse when we apply the idea to particular cases. Imagine that you’ll be woken up each day of a week. Each day, you have no memories of previous days. On AITC’s view, you can’t coherently say “it’s more likely to be Monday through Saturday today than to be Sunday.” Because you’ll in total wake up each day, on his view, such a view is incoherent.

But this just seems ridiculous. Sure if you say make statements about it being more likely to be Monday through Saturday than Sunday you’re not saying something about what the world is like, but you’re saying something about your place in the world. You’re saying something not about what will happen but about what is happening now.

It gets even worse. Imagine that you’ll be put woken up every day for four years that contains a leap-day. Every day that isn’t a leap day, you’ll be given a cake. On the leap-day, however, you get something much worse than a cake—being stabbed in the eye. On AITC’s view, it’s incoherent to, upon waking up, think “probably I won’t be stabbed in the eye today, because it’s likely not a leap day.” This is just completely absurd and implausible.

Or imagine that you’ll be put to sleep and then awoken once during the time Biden is president and once during the time Trump is. When you wake during the time his successor is president, you have no memories of the previous day, and in neither case do you know who is president. On AITC’s, upon waking up, you can’t coherently wonder if Biden is currently president, as that doesn’t pick out a specific fact. Thus, on his view, the sentence “Biden is more likely to be the president than my shoe,” isn’t true. What could be worse for a view than implying that?

To give one last case, imagine that you’ll be put to sleep and woken up twice, and on the second day you’ll have no memory of the first. Each day, a coin will be flipped. It will come up heads on the first day, tails on the second day. On AITC’s view, when looking at the coin that’s about to be flipped, you shouldn’t have a credence associated with it coming up heads when, in a few minutes, you flip it. That’s nuts!

I also don’t think AITC’s view is able to get out of the arguments for SIA without incurring significant cost. Imagine that a coin is flipped. If it comes up heads, you wake up once, while if it comes up tails, you wake up twice, on the second day having no memory of the first day. Suppose that every day you utter some random statement—perhaps “bing bang boom bimb.” Suppose that today you have resolved to utter “bing bang boom bimb.” One can reason:

P(I utter “bing bang boom bimb,” on day 1 and the coin comes up heads)=P(I utter bing bang boom bimb,” on day 1 and the coin comes up tails).

(I utter “bing bang boom bimb,” on day 1 and the coin comes up tails).=P(I utter bing bang boo bimg,” on day 2 and the coin comes up tails).

Thus, tails is twice as likely as heads.

AITC could go two ways. First, he could accept all three and accept that tails is twice as likely as heads, but only because of the uttering of bing bang boom bimb. If one didn’t plan on uttering sentences, their credences should be different. But this is totally crazy! One’s credences in the above scenario shouldn’t change because of their resolution to utter random sentences.

Second, he could reject 1 and think that P(I utter “bing bang boom bimb,” on day 1 and the coin comes up heads) is twice as likely as P(I utter “bing bang boom bimb,” on day 1 and the coin comes up tails). But then after learning it’s currently day one, so that he’s going to utter “bing bang boom bimb,” on day two, he’d either have to violate bayesian conditionalization and say tons of counterintuitive things or think it’s twice as likely that the fair unflipped coin will come up tails as heads.

Finally, I think AITC’s view implies skepticism. On his view, if a theory predicts you’re in state A one time and then state B a million times, and another theory predicts you’re in state B one time and then state A a million times, after waking up and being in state A, you’ll get no update in favor of either theory. For example, if one theory says I’d wake up every day in a red room, and another theory says I’d wake up only every thousand days in a red room, on AITC’s theory, merely waking up in a red room gives no evidence for either view.

Suppose I google “laws of physics,” and find that this is what the standard model is:

The prior probability that this would be right description of the laws of physics is very low—it’s quite specific and random. In contrast, if I’m infinitely reincarnated, I’d be guaranteed to hallucinate that being the laws at least once. Thus, I’ll get a massive update in favor of the theory that I’m reincarnated a bunch of times and am massively deceived all the time, and will end up concluding, with near certainty, that I’m massively deceived about physics—the same point applies also to mathematics, for instance.

Note: this doesn’t apply to SIA, because on SIA, while a theory on which the right laws of physics are the one shown above has a low prior, it gets a massive update, for if it’s right, then a large number of people would see that it’s right. In contrast, on AITC’s view, seeing that only favors theories that make it likelier that you’d see it at least once, so there’s no massive update that cancels out the vanishingly low prior of that being the right law. It doesn’t apply to SSA either, because if you’re repeatedly reincarnated, in most of the incarnations you’ll be accurate about physics, so if you treat the current moment as randomly drawn from the total moments, you’ll get a massive update in of the above imagine accurately representing the laws of physics to cancel out the low prior (the theory that it’s the right law of physics, while having a super low prior, makes it way likely you’d see it when you google “right laws of physics.”)

I also suspect AITC’s view would imply more weird stuff, but it was hard to figure out what it implied in other cases. My suspicion is that it’s not a precise coherent view—it couldn’t give an algorithm for determining credences—but it’s just whatever divvying up of credences seems right in some scenario.

Anyway, hope you enjoy the conversation!

Share this post