50 Lifetimes To Babylon

Brief reflections on time, the Documentary Hypothesis, and barbarism in the Bible. This article is a series of disjoint thoughts, rather than a cohesive narrative.

1 The case for the Documentary Hypothesis or something like it

I just finished Alexander’s Rofe’s Introduction To The Composition Of The Pentateuch and it’s one of the most convincing books I’ve ever read. It argues that the Torah was not written by Moses, but by a variety of disjoint authors with contrary views about things. It then goes on to identify various features of their writing.

The rest of the Torah clearly believes in Mosaic authorship. Nehemiah 8:1 says “They told Ezra the teacher of the Law to bring out the Book of the Law of Moses, which the Lord had commanded for Israel,” clearly talking about the Torah. Joshua 8:31-32 also suggests that the Torah was “the Book of the Law of Moses,” and Kings 2:3 gives the instruction to “Keep the decrees, commands, regulations, and laws written in the Law of Moses.” There are even more passages that suggest Mosaic authorship, and this has been the traditional view of religious Jews, dating back to the Babylonian Talmud at least.

The problem is that this view is false as Rofe convincingly argues!

Many passages in the Bible are quite clear that the Torah was compiled long after the time of Moses. Genesis 12:6 says “At that time the Canaanites were in the land.” But it would make no sense for Moses to say this, because when Moses was writing, the Canaanites were still in the land. It would be like if I said “California was then filled with Californians.” One doesn’t say “P was true then,” if P is currently true and the reader has no reason to think P was ever false.

Deuteronomy 3:11 states “Og king of Bashan was the last of the Rephaites. His bed was decorated with iron and was more than nine cubits long and four cubits wide.[a] It is still in Rabbah of the Ammonites,” but if Moses had just conquered Og, it would make no sense to describe his bed as still being there. It would be like if I said right after moving into my house “my house is still there to this day.”

The Torah also explains how many local cities were named (e.g. Genesis 26:33, 16:13-14, and 31:47). This makes sense if it was written later, and was accounting for cities familiar to readers, but makes no sense if Moses was currently writing about cities that no one had seen as he was wandering through the desert.

Most decisively are cases like Genesis 36:31, which say “These are the kings who reigned in the land of Edom, before any king reigned over the Israelites.” But this implies that this was written after there was an Israelite King. The Book of Judges suggests that the city of Dan was named only after the period of the Judges, but the Torah references the city of Dan, even though the Torah was supposed to be before the period of the judges.

The opening line in Deuteronomy describes Moses addressing the people from the other side of the Jordan. But this would have made no sense to write—one doesn’t describe their own location as the other side of itself.

So the Torah was clearly written long after Moses. But Rofe goes on to show it was written by multiple authors, based on several lines of evidence (this also shows it can’t be from Moses, who was only a single author).

First, the Torah has numerous stories that are clearly duplicates of each other—two different people with different variations on the same basic story. Genesis 1:1-2:4a tells a totally different creation story from Genesis 2:4b-2:23. The stories contradict; the early Genesis story says that humans were made after plants, while the later one describes that when God made humans “no shrub had yet appeared on the earth[a] and no plant had yet sprung up.” If one reads the stories, it’s obvious that they’re two completely different stories without narrative continuity. They also have various stylistic differences and refer to God differently (the first as Elohim, the second as Yahweh).

Genesis 4:17-19 and Genesis 5 have similar but contradictory Geneogies, with different people being the fathers of others, missing generations, and different but similar names (E.g. Cane vs Kennan). The story of the flood repeats God’s vowing to wipe out humans—first in Genesis 6:5-8, next in Genesis 6:9-13. The story has God repeat his vow not to wipe out humans to Noah twice, in different contexts, and has contradictory numbers of animals on the ark (one version says two of every animal, the other two of every animal except seven of each clean animal and bird).

There are more of these, but I’ll just include one last example: in Genesis, there are three back to back stories of Patriarchs passing off their wives as their sisters so that people don’t kill them to sleep with their wives. This happens twice with Abraham and once with Isaac—both Abraham and Isaac fool a fellow named Abimelech. It’s much more plausible that these are duplicates of the same story from different authors than it is that someone wanted to convince you that this happened multiple times. This same event surely didn’t happen three times, twice being done by Abraham, once by Isaac, wherein Abraham and Isaac dupe the same guy!

There’s also a contradiction in the naming of Beer Sh’eba—Genesis 21:22-32 says it was named by Abraham, Genesis 26: 26-33 says it was named by Isaac. God announces himself to Moses twice at the burning bush, in one of the times saying this was the first time he revealed himself to humans by the name Yahweh, which contradicts earlier proclamations in Genesis that God was called Yahweh in the time shortly after Adam. There are also contradictory lists of Holidays in different books of the Pentateuch.

This summary of the 4 sources provides a helpful description of what makes them unique. J is distinct in that

God is referred to as Yahweh (translated as LORD [small caps] in English).

The holy mountain is called Sinai.

God is anthropomorphized—that is, he is given human characteristics and feelings. (He walks in the garden and talks with Adam.)

The natives of Palestine are called Canaanites.

Some examples are the story of Adam and Eve (see Genesis 2:4–25) and the account of the Ten Plagues (see Exodus 7:14—10:29).

E is distinct in that:

It emphasizes prophecy.

God is referred to as Elohim (“Lord God” in English translation).

The holy mountain is Horeb.

The natives of Palestine are called Amorites.

God speaks in dreams.

Some examples are the sacrifice of Isaac (see Genesis, chapter 22) and the Ten Commandments (see Exodus 20:1–17).

D is distinct in that:

The book of Deuteronomy is a retelling of the stories of Exodus through Numbers (Deuteronomy means “second law”).

Deuteronomy interprets Israel’s history as a cycle of God’s forgiveness and renewal of the Covenant, followed by the people’s failure to live the Covenant, followed by the bad things that happen to them as punishment.

It emphasizes the Israelites’ covenantal obligation.

The holy mountain is Horeb.

It emphasizes law and morals.

An example is the Book of Deuteronomy

P is distinct in its:

emphasis on Temple cult and worship emphasis on the southern kingdom of Judah (because that is the location of Jerusalem and the Temple where cultic worship occurs)

emphasis on the role of the Levites, the priestly class or tribe

emphasis on genealogies and tribal lists, which established the different groups in Israelite society, including the priestly class

emphasis on order and the majesty of God and creation

examples: first Creation story (see Genesis 1:1—2:4), the Book of Leviticus

Finally, there are completely different writing styles from different sources. As the blogger Little Foxling (who has an excellent, though no longer active, blog) says:

The section called D has many characteristics that unite it. It contains a unified purpose, nomenclature, view of the law, view of history, ideology, theology, sociology, political science and more. In short, there are many phenomenon that appear again and again in D but do not appear elsewhere in the Torah, or appear with less frequency. Moreover, there are phenomenon absent in D that are common in the rest of the Torah. I can not go through all of them in this post, but let us take two examples.

1. The word Anoki. The Torah switches off usage between Ani and Anoki, using Ani 182 times and Anoki 141 times. Yet, in D, Anoki is used 53 times and Ani is used twice.

2. The Circular Inclusio. This sentence structure appears once in D and at least 121 times outside of D ( I am aware of 121 times, but I can’t be sure if there are more since there’s no way to check for this in Bar Ilan.

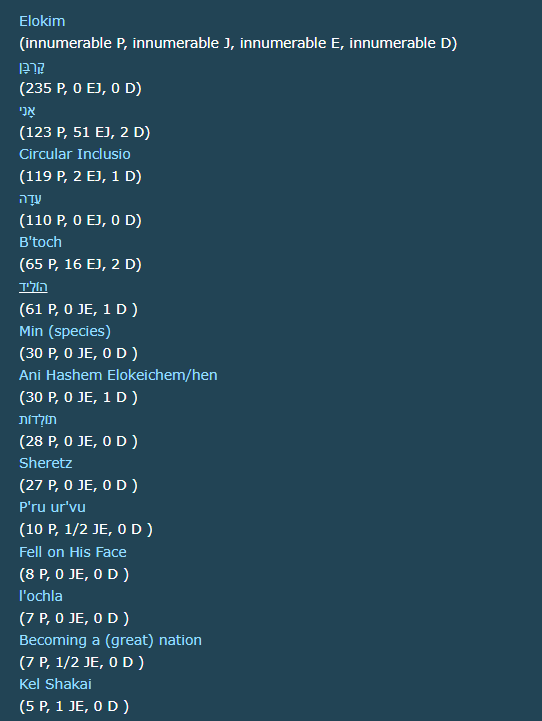

I won’t walk through everything unique about each source, but similar stylistic points are true of other sources (e.g. P). The word אֲדָמָה, for example, is almost never used in P—only 5 times—while used 90 times in the others. עֵדָה appears 110 times, always in P. There’s a long list of words that appear almost exclusively in P:

It’s often claimed that this reflects thematic differences. But this is wildly implausible; many of the words aren’t used differently because of the person. אָנִי means I am (clearly not something only the priestly sources would want to express), the Circular Inclusio is a kind of sentence (one that starts and ends with a phrase like “I am the lord your God,” which wouldn’t be limited to the priestly sources; הוליד means to father, but fathering isn’t only described in the Priestly source. In Deuteronomy, the phrase יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ meaning Yahweh your God, appears 234 times, while only 10 times in the other books. This can’t be plausibly explained stylistically.

For this reason, I conclude the Torah had at least 4 different authors, with radically different visions and stylistic purposes. The traditional view is indefensible.

2 50 Lifetimes To Babylon

Suppose you had a chain of people who each had a child on the last day of their life. Imagine, for the sake of simplicity, that they each live 50 years and then birth a child. How many lifetimes back were the Babylonians around?

The answer is roughly 50. We’re 50 lifetimes removed from Babylon. If the lifetimes are longer—say, 100 years—we’re only 25 lifetimes removed from Babylon. Only 25 long lives would have passed since the time the Babylonians were around.

The founding of America—which seems so far away, like ancient history—is just over two lifetimes back. When your elderly grandparents were around, computers weren’t invented, World War two hadn’t happened yet (if they’re sufficiently old—my grandparents, who sometimes read this blog, are spry and youthful!), and watergate wouldn’t happen for some time.

Go back twice the length of time that your elderly grandmother has been around, and you’d be able to meet George Washington. Joe Biden was born nearer to the time of Lincoln’s inauguration than his own. Go back a few more lifetimes and you could meet Thomas Aquinas, just a bit before that and you could witness the signing of the Magna Carta.

We’re only 25 lifetimes of long-lived people from Babylon, only 60 of these from the start of civilization. That’s a remarkably short time. Go into a big lecture hall—together the people in that room will experience more years of life than there have been years since civilization started.

The universe is grand and old, having been around for many billions of years. We’re about a hundred million lifetimes from the big bang. Still, that’s not that long. More years of life have been experienced by humans in the last two years than years have passed since the Big Bang. If all of Earth’s existence was a year, humans would have only been around for the last two minutes.

Many people think that the universe is infinitely old, that reality had no beginning, but each point was preceded by a further point, going infinitely far back. We are, on such a picture, no finite number of grandparents back to the beginning. There was no beginning, every moment was preceded by one before it, just as there’s no smallest number.

Life has been around on Earth for billions of years. Life is truly unfathomably old, surpassed only by the universe. Civilization, in contrast, is in its infancy, having just taken its baby steps, just learned to walk. The things you read about in history books are just a few dozen grandfathers away at most, many of them a single-digit number of grandfathers away.

We’re just 25 old-men from Babylon. Pretty weird when you think about it.

3 Biblical horror

People often describe being struck by the brilliance of the Bible when they read it. I find this mysterious, as I’m struck by the opposite.

Even a cursory familiarity with the Bible reveals obvious contradictions. For example, Exodus 20:5 says:

You shall not bow down to them or serve them. For I the LORD your God am an impassioned God, visiting the guilt of the parents upon the children, upon the third and upon the fourth generations of those who reject Me.

For one, this sort of collective punishment is clearly evil and Barbaric! One should be only punished for their own sins. For another, it quite clearly contradicts the rest of the Bible. Ezekiel 18:19-23 says “The son will not bear the punishment for the sin of the father.” God murders millions of innocent Egyptian children, kills Aron’s sons for delivering the wrong sort of fire, commands the Israelites to go to lands and wipe out people viciously, approves of slavery, and so on. There is endless discussion of bizarre rituals, of the type that might be expected of certain primitive humans, but not of God. The god of the Bible doesn’t seem like God at all.

I find the traditional view that the Bible breathtakingly wise to be impossible to fathom. I have exactly the opposite reaction when I read it. Perhaps, like Augustine or Lewis, I will outgrow this view, and see the wisdom. Perhaps the deep wisdom is the sort of thing that will forever elude me, or perhaps it is simply not there. Whatever the case, if there is deep wisdom, I find myself unable to find it.

The only parts of the Bible that ever really struck me as wise or profound are Ecclesiastes and maybe Job.

Ecclesiastes seems to have been written by something of a nihilist, which is kinda funny. Job is interesting in its grappling with the problem of evil but the answer given is ultimately pretty unsatisfying.

I read Genesis and most of Exodus as a young child and was similarly struck by the horror of it. I recall reading about the killing of the first-born children in the final plague in Exodus and imagining myself as one of those children, killed for no fault of their own by god. It was very distressing, and I suspect my moral horror had more to do with my apostasy than the logical contradictions.